In every era, society has tried to capture a sense of community. The ancient Greeks viewed it through the lens of the polis. Medieval societies centered community around the church. Our understanding of community shifts along with our cultural contexts, technological advancements, and social changes.

How do we conceive of, experience, and practice community today? And what impact might this have on how we seek to reach our neighbors with the gospel?

Is community just comfortable homogeneity?

Modern Western cultures arguably tend to reduce community to networks of convenience and shared interests. And the church, at times, looks little different. Today, many Christian communities have become among the most homogeneous gatherings in society.

The word “community” comes from the Latin communitas, suggesting a shared burden or gift. But how often do we truly share our burdens across differences rather than simply finding others with similar loads? Has the Christian community gone from being an inclusive, boundary-breaking, radical concept to an exclusive club that prioritizes sameness over genuine, intentional, and even uncomfortable connections? Have we mistaken comfort for community? Have we confused similarity with solidarity?

And what message do we send when our churches and small groups function as exclusive clubs? If community is meant to reflect something of God’s character—inclusive, generous, redemptive—what does it say when our communities resemble walled gardens accessible only to those who look, think, and act like us? As Priya Parker observes in The Art of Gathering, “The way we gather matters. Gatherings occupy our days and help shape the world we live in, both in our intimate and public spheres.”1 Yet how often do our gatherings genuinely create space for the stranger, the outsider, or the person who doesn’t already belong?

The early church’s boundary-crossing community

When we open the pages of the New Testament, the early church provides us a compelling example of both the possibilities and the challenges of building authentic community. In it we encounter a radical vision that challenges our modern, comfortable notions of community.

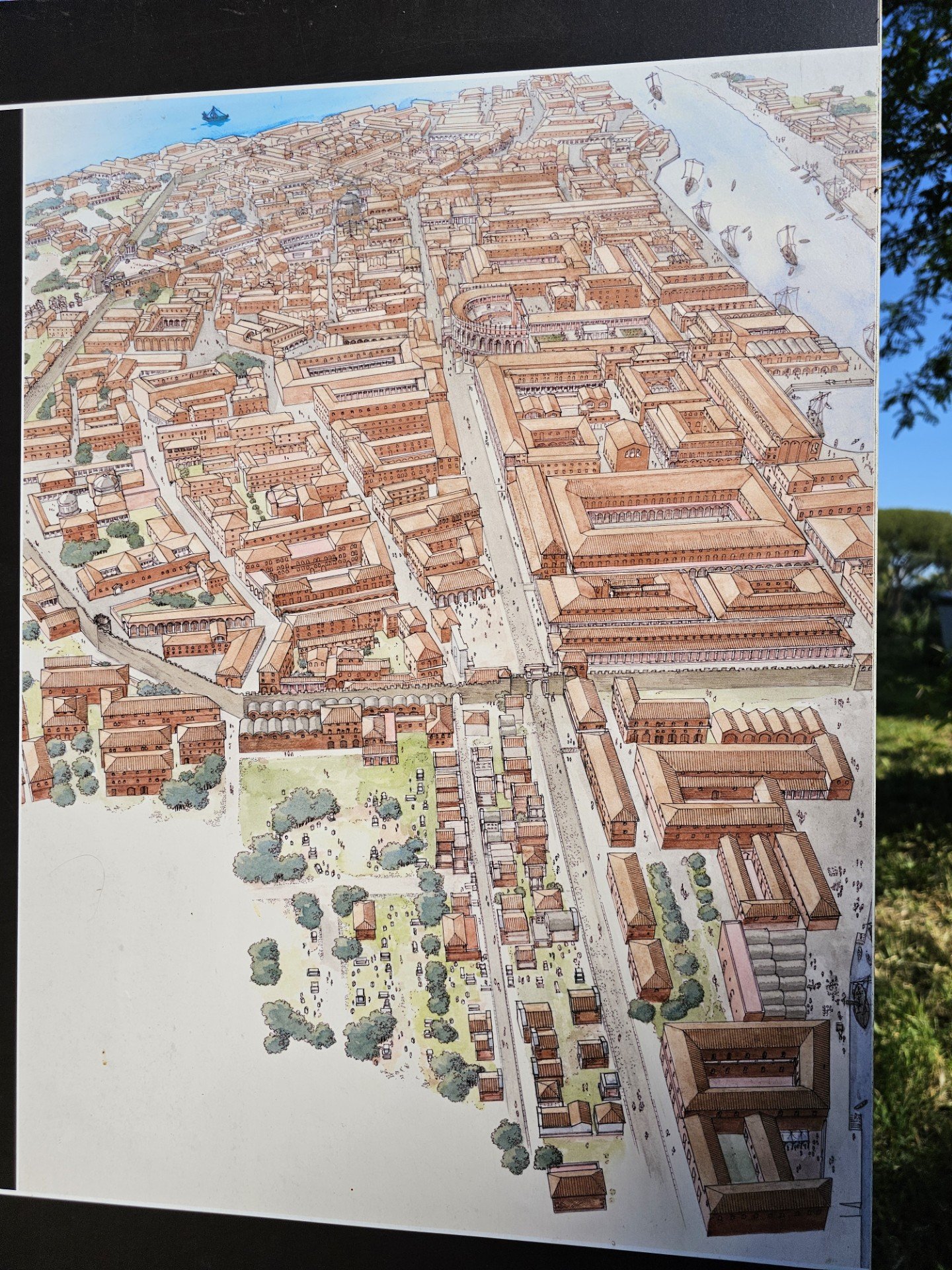

The first Christians didn’t gather based on socioeconomic status, educational background, or cultural preferences. Their community crossed boundaries of ethnicity, class, and gender in ways that were shocking to the surrounding society. They attempted to create spaces where, as Paul wrote, “there is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female” (Gal 3:28).

Was it messy? Absolutely. Was it difficult? Without question. The New Testament letters are filled with corrections whenever these communities failed to live up to this ideal. The wealthy ate before the poor arrived (1 Cor 11:17–34), ethnic tensions simmered beneath the surface (Gal 2:11–14; Acts 6:1–7), and power dynamics threatened to replicate the hierarchies of the outside world (e.g., 1 Cor 1:10–13; 3:3–9; Jas 2:1–9).

The New Testament letters along with Acts reveal communities struggling with unity despite significant differences. They didn’t always succeed, but they continued trying, gathering, and sharing meals across boundaries that the surrounding culture deemed impermeable. Their community was drastically counter-cultural—even as it was demanding.

And this inward experience of community did not stay confined, but moved outward. In Acts 1:12–26, we observe the nascent church “with one accord … devoting themselves to prayer,” waiting for the Spirit as Christ commanded. What follows is Pentecost (Acts 2:1–41). The connection between these two is not incidental. As Darrell Bock observes,

we gain a glimpse of community life and then observe the community engaging the larger culture in witness. The juxtaposition is intentional. The community is not only meant to be inwardly focused on its worship, obedience, growth, and nurture, but also to move out into the world in testimony.2

Arriving at Acts 2:42–47, we observe the early church’s practice of community—both internally and with outsiders. These believers held possessions in common while continuing to attend the temple, reflecting their embrace of the Messiah. Their messianic faith didn’t separate them from the broader Jewish community. Rather, their interaction and engagement with outsiders sparked continued growth (v. 47). In Acts, we never see a community so inwardly focused that taking the message to outsiders is forgotten or ignored.

Hard-won early Christian community

What exactly characterized the early Christian community that enabled them to cross boundaries and reach people of all types? How did they do this?

The early church was defined by four traits. In Acts 2:42, we read that “they devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and the fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers.” Repeatedly, we see unity of mind and the work of basic community in these four areas. These groups were bonded in ways that transcended individual personal preferences or similarities.

Luke uses “fellowship,” or “sharing in common” (κοινωνία), to highlight the personal, interactive character of relationships in the early church—the sense of connection to, for, and between one another. The word also carries overtones of mutual material support. In Acts 2:44–45 (see also 4:32–37), we read about how this community practiced mutual care for both those within it and those who had come to believe anew.

Whether “breaking bread” meant the Lord’s Supper or meal sharing remains unclear. In the early church, the Lord’s Supper may have been part of a larger meal (see 1 Cor 11:17–34). But regardless, the broader context of “breaking bread” suggests intimate interaction and mutual acceptance that were essential parts of community life. Their “fellowship” extended beyond the sacred space and into their homes.

Luke emphasizes prayer as an essential component of this community. As followers of Christ, we need God’s direction and depend on him for everything. Community life and work didn’t happen through good feelings and positive thinking, but by actively submitting to God and following his direction.

Finally, Luke remarks that “they devoted themselves” to all these things, indicating perseverance and tremendous persistence. This “ongoing devotion” employs a construction of a verb meaning “to persevere,” “to persist.” In other words, they didn’t seek the path of least resistance, attempting to create seamless integration. Instead, they chose to persevere in relationships.

Our struggle—and solution—to developing community

What we learn from the Acts church is the importance of investing in community, pursuing intimate and strong relationships—even across differences.

Yet we find ourselves in an individualistic culture that doesn’t allow for organic community growth. Cities, suburban life, and societal changes, including parenting and work patterns, all make building community challenging. Our churches create programs to help us navigate these challenges amidst busy schedules, often resembling moves on a game board.

But what if these individual needs frequently take priority over communal ones? Today, many of our gatherings are homogenous, like-minded, and so targeted that we cannot even imagine the challenge of building bridges with those from vastly different backgrounds. Churches can become intensely regimented, and structure is important. But we should ask, at what point might it impede growth? Yes, we all long to be seen, known, and loved within our particular circumstances. But what if there’s more to community than fulfilling our own personal desires?

In my own life, I often find myself asking, who are “my people”? But should we, as followers of Christ, have these inner circles—and feel comfortable within them? Our desire to find relationships among those with bonds and shared histories is laudable, but when done with exclusivity, we contradict the Bible’s expectation for Christian community. Birds of a feather certainly do flock together, and having similar backgrounds helps build friendships. But when an individual happens to be different, finding space for belonging becomes complicated. One can often find greater unity in a town sports league than in a church youth group.

What if, instead of first and foremost pursuing that sense of belonging for ourselves, our vision for community centered more on our own participation, what we provide for others? Instead of merely focusing on what we receive from the church, we ought to ask how we can contribute towards creating community for others. In fact, what if, as followers of Christ, we are specifically called to build places of belonging for others who might not belong anywhere else?

What if, as followers of Christ, we are specifically called to build places of belonging for others who might not belong anywhere else?

The comfort and inconvenience of community

And here is the paradox of Christian community: It simultaneously brings comfort, yet calls us to discomfort (inconvenience) as we pursue it.

As an immigrant, I know well this experience of discomfort well. I’m required to navigate between circles that can be quite fluid and changing. This comes at a cost. It requires time and a willingness to embrace different personalities, points of view, and social and political backgrounds.

Yet we’re drawn to comfort. We want our community life to be seamless and effortless. But community was never meant to be easy. It was always meant to be inconvenient, awkward, and challenging. Genuine connection requires us to step outside our comfort zone, be vulnerable, take risks, and deliberately engage in the messy work of building relationships across differences.

But without that tension and struggle across differences, it’s not really a Christian community, is it? The early church didn’t gather people of similar demographics for comfortable conversation—they created a radical new family that transcended the boundaries of their deeply stratified society. As followers of Christ, we are called to live radically different lives that will be hard, complicated, sacrificial, and unaligned with what the world tells us to do. But that is what Jesus did.

In order to build diverse communities that flourish, we should be cautious about overemphasizing differences among people. Instead, we ought to be curious and eager to learn from each other. A church may need specialized ministries, but it should also find ways to integrate. Our communities will flourish when people from diverse backgrounds interact with one another in respectful ways, allowing us to learn from each other.

At the same time, we need to see people in all their complexity. Individuals are unique with diverse backgrounds and experiences. To truly see people and understand the nuances that make them who they are, we must take the time to appreciate their complex and rich heritage. Only then can we genuinely comprehend each other.

Often in church and Christian circles, we skip right past heritage, socioeconomic backgrounds, family formation, and social class, jumping directly to “What is the Christian thing to do?” We often presume upon the “other” to assimilate. Yet we need to allow each person to bring their whole selves with all their intricacies to the table. Being a Christian is our identity, but it doesn’t require forgetting our ethnicity and background.

We often desire those around us to conform to our comfort, ensuring they align with who we are. However, for a deep and rich community to flourish, we have to be willing to enter into gritty, complicated, and honest relationships with those who may be quite different from us. But in so doing, it can reveal parts of ourselves we might not ever have known existed!

Community is not a destination, but a lifelong journey where we constantly make ourselves vulnerable, challenge our instincts to seek comfort and familiarity, and strive to be understanding and radically inclusive. Do we have the courage to extend ourselves to others who seem the most different?

Conclusion

On a bright Saturday morning, we attended a prayer meeting at an old friend’s home. I walked into the room and sat at the end of a row. Looking around, I smiled at those around me. There were a few new faces, but most were known to me—and all seemed welcoming. It felt like home. Being around those I had known and loved for years felt welcoming and easy.

However, I also recall the times when it was complicated and painful. There have been moments of hurt and anger. This sense of community and belonging was a hard one. It took perseverance among its members, who stayed through hard times, navigated disagreement and differences of opinion. We walked through joy and loss together. Over time its rough edges got smoothed out—and intimacy grew.

Participation led itself to a natural place of belonging.

So I ask: Are we perpetuating a pattern of “Christian community” that isn’t a community at all, but rather something more like a club requiring a particular pedigree for membership? True Christian community can be uncomfortable. But what if community was never meant to be easy or comfortable? What if this discomfort is precisely what we’re called to cultivate as Christ’s followers?

In fact, this place of discomfort may be the very space where authentic Christian community begins.

Resources for further study

Made to Belong: Five Practices for Cultivating Community in a Disconnected World

Price: $12.99

-->Regular price: $12.99

The Compelling Community: Where God’s Power Makes a Church Attractive

Save $2.80 (20%)

Price: $11.19

-->Regular price: $13.99

Mobile Ed: Ministering in Multiethnic Contexts Bundle (2 courses)

Save $118.30 (35%)

Price: $219.69

-->Regular price: $337.99

Redemptive Kingdom Diversity: A Biblical Theology of the People of God

Price: $24.99

-->Regular price: $24.99

The New Testament in Color: A Multiethnic Bible Commentary

Save $9.60 (20%)

Price: $38.39

-->Regular price: $47.99

No Longer Strangers: Transforming Evangelism with Immigrant Communities

Save $4.20 (20%)

Price: $16.79

-->Regular price: $20.99

The Next Evangelicalism: Freeing the Church from Western Cultural Captivity

Save $3.20 (20%)

Price: $12.79

-->Regular price: $15.99

Related resources

What Makes a Church Healthy? | Mark Dever

Is Your Church Truly Healthy? Look to Love, Not Metrics

Why Diversity in Worship Matters (and How to Achieve It)

Reconciliation in the Bible: How to Heal Broken Relationships

3 days ago

10

3 days ago

10

English (US) ·

English (US) ·