Because all biblical documents were copied by hand for nearly three thousand years, it is not surprising that its manuscripts contain differences (variants).

Textual criticism is the discipline that guides us in establishing what the authors of the Bible wrote. This is especially important for those who value the Bible as God’s Word. The work of textual critics enables us to know with confidence what God has said through the human authors.

In this article, we’ll present the basic principles of textual criticism:

- We’ll explore how we get variants, i.e., how changes and errors occur in the transmission process

- We’ll present the types of evidence we use to evaluate such variants

- We’ll provide six key principles to use when evaluating variants

Understanding how changes and errors occur in transmission

While there is a range in degree and nature of the variants, several common scribal mistakes account for the majority of the differences in the biblical manuscripts.

Some mistakes are similar to the kind anyone would make when copying a text by hand, but others are unique to the ways ancient Greek or Hebrew were written. Because the earliest Greek manuscripts were written in scriptio continua (all capital letters with no spaces between words), and Hebrew does not distinguish between upper- and lowercase letters1 and was originally written without vowels, a number of difficulties can arise in determining the actual wording and sentence structure intended by the original author. In addition, for the most part, neither language incorporated punctuation, paragraphing, section headings, or end-of-the-line hyphenation. Some manuscripts were written down by scribes as the text was read aloud to them, increasing the possibility for misunderstanding.

The combination of these features proved a challenging task for copyists—even those working in their first language—as well as for translators working in a second (or third or fourth) language. The process resulted in many unintentional errors of spelling, omission, and addition.

Manuscripts also reflect intentional changes that scribes and translators made to the text to smooth out syntax, clarify meaning, or add information.

But every change—intentional or not—resulted in textual variants for textual critics to sort out. The most common types of variants are as follows.

1. Omissions

During the process of copying, scribes sometimes inadvertently omitted letters, words, or even phrases that were in their source document or exemplar. Textual critics are able to discern the reason for many common errors, as we illustrate in the following sections. At the same time, some errors defy ready explanation.

Haplography. Some omissions of text occur when a copyist missed a portion of a repeated sequence of letters or words. The result is a haplography—a “single writing” in place of a “double” repetition present in the exemplar. Such oversight could be caused by the scribe’s eyes skipping from one word or letter combination to another word or letter combination that is similar or identical. For example, an English typist could easily type “to th ends of the arth,” unintentionally skipping one e where there were two intended.2 Haplography often occurs because of homoeoteleuton (literally, “same ending”), when two lines in the exemplar end in the same way. This type of error occurs in both Testaments.

Parablepsis. The term parablepsis applies to scribal errors caused by the eye skipping from one part of the text to another. It is similar to haplography in that it often involves an omission of text caused by repeated letters, words, or phrases. However, parablepsis is not just the omission of the repeated element; it involves jumping from one repeated element to another and omitting everything in between. When copying a manuscript, the scribe’s eyes skipped “from one letter or cluster of letters to a similar looking line,” unintentionally leaving out the material between the two.3 Technically, parablepsis could also be responsible for textual additions if the scribe loses his place on the page or in the line and writes a word or phrase over again (see dittography below).

2. Additions

Dittography. In contrast to skipping over letters, words, or sections, scribes sometimes unintentionally wrote things twice. This “double writing” or dittography could involve a single letter or several words. Emanuel Tov notes that the components in some manuscripts may not even be identical, “since at a later stage one of the two words was sometimes adapted to the context.”4

Conflation. Sometimes scribes combined elements found in two or more manuscripts and created a longer reading. This combination is called conflation. Conflation may have resulted when the scribe was unwilling to choose between the two variants and thus included both.

Some instances of conflation could have been unintentional errors, when a scribe inadvertently added something from another text in his memory, such as a wording difference from the Gospel of Luke that naturally flows out of the scribe’s memory when copying the same story in Mark (see also harmonization below). Conflation may also have resulted when explanatory marginal notes or corrections in a manuscript were integrated—whether intentionally or not—into the running text in the new manuscript (see also glosses below).

Glosses. In the course of using their copies of the Bible, early believers sometimes wrote explanations, interpretations of words or phrases, or commentaries of the church fathers in the margins of the manuscript or between the lines of text. An explanation of this type is called a gloss.

In the case of the earliest OT texts, transmission took place over hundreds of years, so that the manuscripts would have contained outdated references that were meaningless to a changing readership. As a modern example, if a researcher on the history of Rye Country Day School came across the name Barbara Pierce in copies of school documents, he might write “Bush” in the margin or above “Pierce” in the text. If others used his notes later in their own work, they might simply refer to “Barbara Bush,” or they might even conflate the “variants” and refer to “Barbara Pierce Bush.” When similar glosses occurred in handwritten biblical manuscripts, it was not always clear to later copyists whether a marginal note was an addition or an accidentally omitted word inserted by the earlier scribe.5

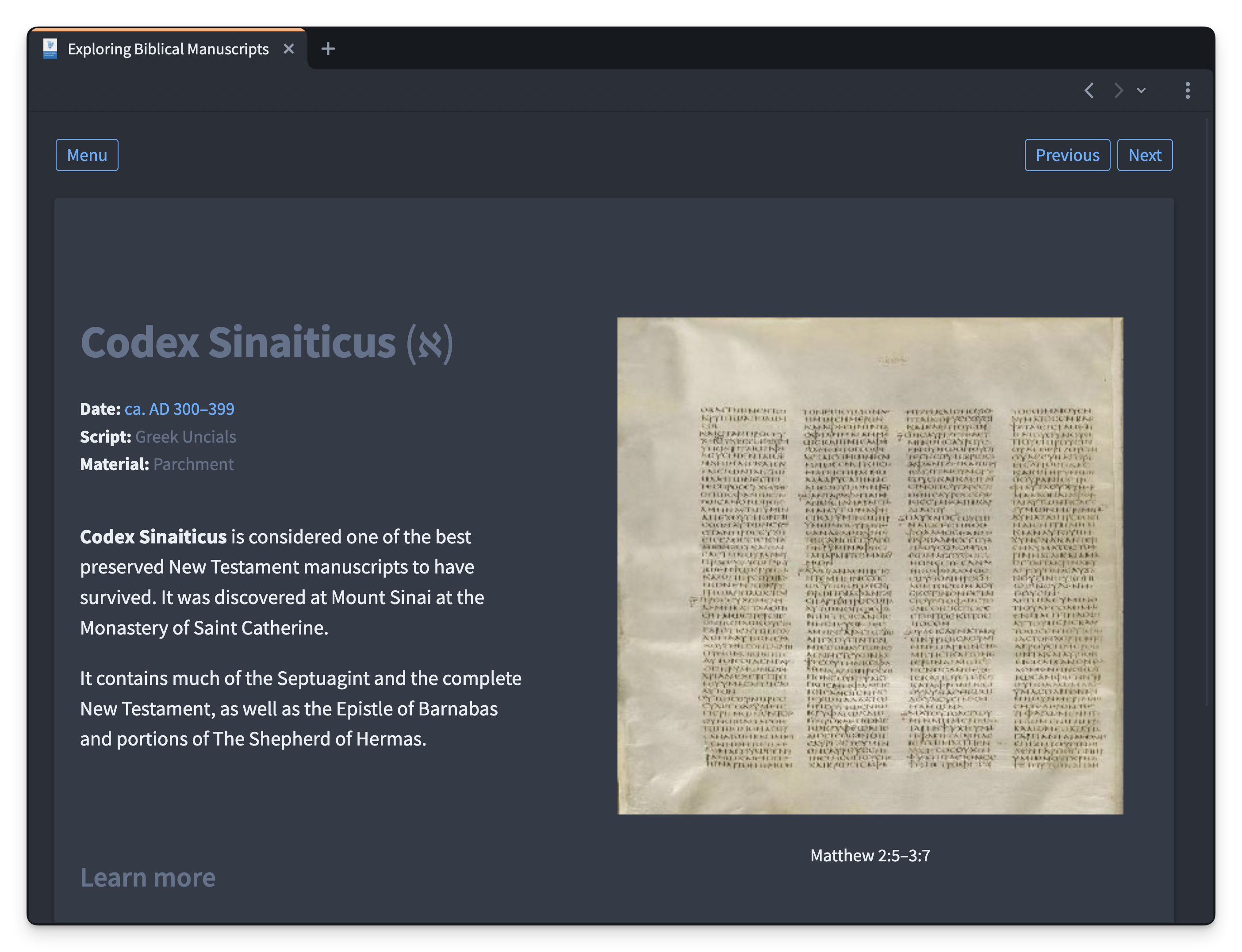

Logos’s Exploring Biblical Manuscripts interactive provides a visual guide to learn about Old and New Testament witnesses.

3. Misspellings

A large number of textual variants are the result of spelling differences or errors. It may be that the spelling of a word changed over time. Some differences occurred when a scribe inadvertently switched letters, words, or sounds around in the course of copying. Others were the result of sloppy penmanship that made it difficult for a copyist to discern what his source manuscript read. Still others happened when scribes misheard manuscripts being read aloud for them to record. Consider a room full of English speakers asked to write the word “occurrence.” Some might write “occurence,” while others might write “ocurence” or “ocurrence.”

Metathesis is the accidental transposing of letters, words, or even sounds. Tov and Kyle McCarter define metathesis more narrowly as the inadvertent switching of two adjacent letters,6 but David Black allows for entire words to metathesize,7 and Matthew DeMoss says transposition of sequential sounds is also metathesis.8

Mistaken letters. Other misspellings in manuscripts arose when scribes mistook letters for other, similar-looking letters. Such mistakes could have been caused by the exemplar—perhaps it was damaged or not written clearly—or they could have resulted from the copyist—he or she may have been working in poor light, may have suffered from poor eyesight, or may have failed to examine the exemplar carefully. For whatever reason, the scribe read the text as representing a different word or combination of words than intended.

Homophony. Another type of spelling error resulted from homophony—confusion of words that sound alike but are spelled differently. A common English homophone is the trio of words “their,” “they’re,” and “there.” Even people familiar with the words can easily confuse them. In Greek, for example, there are a number of vowels and diphthongs (double vowels) for which the pronunciations came to be identical over time. These are η (ē), ι (i), υ (y), and ει (ei), and sometimes οι (oi) and υι (ui). Confusing these letters is referred to as itacism.

In manuscripts of the Bible, itacisms and other mistakes of homophony could have occurred when a scribe copied from another manuscript, but they are more likely to have occurred when scribes wrote down texts that were read aloud to them.

4. Intentional changes

Most of the textual variation described above represents unintentional changes. However, sometimes textual changes appear to have been intentional.

Some of the scribes’ changes were as innocuous as smoothing syntax, correcting bad grammar, or updating an older spelling. Other changes reflect a concern for accuracy and consistency between similar texts. Still others demonstrate scribal zeal for theological clarity where the text may have been ambiguous.

Textual criticism is never an exact science, and the identification of intentional changes along with the rationale behind such changes can be controversial. Nonetheless, the following examples illustrate the purposes behind some changes that appear to be intentional.

Spelling and grammar. Languages change over time and location, a phenomenon that is obvious in the English language. For example, “colour” and “analyse” became “color” and “analyze” when they crossed the Atlantic Ocean, and “you all” or “all of you” became “y’all” when it moved south.

The languages of the Bible also changed over time and location. Hebrew changed more than Greek since the composition and transmission of the OT took place over a much longer period of time than the NT. Scribes sometimes updated spellings and grammar to reflect changes in usage. Most spelling changes are insignificant in textual criticism, but sometimes variation in spelling created ambiguity—and thus uncertainty for scribes.

Harmonization. Several biblical books have similar, even parallel content. For example, much of the content of Samuel and Kings is repeated in the books of Chronicles. The three Synoptic Gospels (Mark, Matthew, and Luke) also share a lot of common material. In addition to these large-scale similarities, there are shorter parallel texts, such as David’s victory song, which is recorded in both 2 Samuel 22 and Psalm 18. A significant amount of repetition can occur even with a single passage, as in Genesis 1.

When they encountered parallel passages or significant repetition, scribes sometimes adjusted the text so that the details matched. This process is called harmonization.

Theological changes. Some changes in the biblical text seem to have been made for theological reasons, whether to protect the portrayal of God or to correct what seemed to be an error in the content.

While most scholars agree that such modifications took place, Tov contends that “the number of such changes is probably smaller than is usually assumed” since most scholars use the same handful of examples.9 When variants appear that seem to be theological in nature, scholars speculate (and often debate) whether the changes were made intentionally.

Summary

A simple review is as follows:

- Haplography: Writing something once instead of twice

- Parablepsis: “Eye-skipping” that overlooks and eliminates or repeats text

- Dittography: Writing something twice instead of once

- Conflation: Combining multiple readings

- Glosses: Incorporating marginal notes into the text

- Metathesis: Switching the order of letters or words

- Mistaken letters: Confusing one letter for a similar-looking letter

- Homophony: Confusing words that sound alike

- Spelling and grammar: Updating or improving the text

- Harmonization: Bringing similar passages into conformity

- Theological changes: Protecting the text from misunderstanding

Evaluating these variants in the biblical text

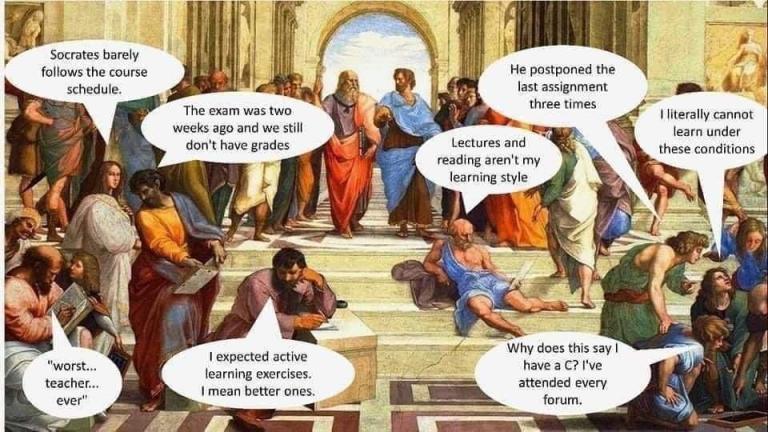

Although the scribes of biblical manuscripts were, for the most part, well trained and cautious, they were human, and humans make mistakes. The task of the textual critic is to determine when copyists made mistakes or intentional changes.

The process of textual criticism involves considering external evidence and several types of internal evidence, regardless of the Testament under consideration.

External evidence

External evidence involves the quality, quantity, and textual affiliation of the manuscripts that witness to variant readings.

This type of evidence is not concerned with the context of a passage, which reading seems to make the most sense, or even how a variant developed. It focuses on evidence external to the actual reading: “In what kinds of manuscripts is a given variant found?”

Internal evidence

Internal evidence is concerned with what happened within the text to cause the occurrence of variant readings. The basic principle behind evaluation of internal evidence is this: “The reading that best explains the origin of the other readings is probably original.”10

Scribes were prone to making certain kinds of mistakes in their manuscripts (see above). When textual critics assess variant readings based on knowledge of scribal habits, they are assessing the transcriptional probability of a particular reading. Thus, transcriptional probability is all about scribal habits. For each variation unit, the question of the textual critic is: Which change is a scribe or copyist more likely to have made?

Authors also exhibit particular styles of writing, preferences in vocabulary, and systems of belief. When textual critics consider variant readings based on the larger context of a particular author’s style and theology, they are assessing the intrinsic probability of a given reading.

Every author has a particular style in their grammar and vocabulary choices, and every biblical book reflects an author’s theology. Because scribes made intentional changes at times to smooth grammar or clarify difficult texts, not every reading represents what the original authors wrote. Textual critics try to determine which variants best reflect a given author’s style and theology based on the larger context of a chapter or book (i.e., “Which of these two words is Paul more likely to have used in this context?”). However, matters such as style and theology can be highly subjective, so wise textual critics are not dogmatic in their assessments of intrinsic probability.

6 principles for conducting textual criticism

Determining which variant offers the best reading is an art as well as a science, but there is a basic process that controls the evaluation of variants. When weighing each type of evidence—external and internal—a set of principles guides the process (although not all principles apply in every instance).

1. Prefer the reading found in the oldest manuscripts

Generally, older manuscripts are more reliable than later manuscripts because they are closer in time to the original composition and have theoretically had fewer opportunities for errors to develop.

However, even our oldest manuscripts are copies, so this principle has limitations. An early manuscript is just as likely to include errors or deliberate changes. At the same time, a late manuscript may be only one or two generations of careful copying from a very ancient one and could preserve an early reading.

2. Prefer the reading that has multiple attestation

If a reading occurs only in an isolated manuscript, it is less likely that such a singular reading preserves the Ausgangstext (“initial text”). Normally you would expect the best and oldest reading to be in more than one or two witnesses.

At the same time, the prolific copying of the NT in the Middle Ages resulted in many hundreds of copies of the later Byzantine type of text. Thus, it frequently occurs that the textual weighs the reading of a few older manuscripts against the reading of many later ones. In such cases, the older witnesses tend to be preferred over the many later witnesses.

3. Prefer the reading found in a variety of manuscripts

A reading that is carried by several textual traditions (e.g., a reading that is carried by both Alexandrian and Byzantine witnesses) is more likely to be the earliest form of the text than one that occurs in a single textual tradition (e.g., only in the Byzantine witnesses) or in a family of manuscripts.11

Logos’s Guides include Apparatuses and Textual Commentary sections to aid your textual criticism work.

4. Prefer the shorter reading (lectio brevior)

If copyists did intentionally smooth out a stylistic difficulty or make a passage easier to understand, they were more likely to add to the sacred text than to take away from it. Thus, a shorter reading is generally considered to be more original than a longer one.

However, the scribe of a shorter text may have unintentionally omitted something, so this principle should be applied cautiously.12

5. Prefer the more difficult reading (lectio difficilior)

Scribes sometimes made changes intentionally to make a difficult text easier to understand. It is unlikely that a scribe would change the text to make it more difficult to read. Because of this, the textual critic generally considers a more difficult reading more likely to be the earliest form. This principle applies to grammatical or stylistic difficulties as well as conceptual or theological difficulties.

However, we should be cautious when applying this rule since an accidentally corrupted text could also yield a difficult or nonsense reading that later scribes would have corrected.

6. Prefer the reading that best fits the author

Variant readings with vocabulary and syntax that seem out of place for a particular author are candidates for scribal alteration. Variants that reflect a different theology than the dominant theology of a passage or book may also be suspect. Generally, the textual critic should consider the variant that best represents the author’s broader style and intent.

Conclusion

Textual criticism is both a science and an art. While basic principles guide the process, some conclusions involve a degree of subjectivity. Learning these principles is the starting point for scientific inquiry, but developing competence in the art of textual criticism takes time and practice. As Black notes:

Of course, greatest caution must be exercised in applying these principles. They are inferences rather than axiomatic rules. Indeed, it is not uncommon for two or more principles to conflict. Hence none of them can be applied in a mechanical or unthinking fashion. If in the end you are still undecided, you should pay special attention to external evidence, as it is less subjective and more reliable.13

This article is adapted from Wendy Widder and Amy Anderson, Textual Criticism of the Bible: Revised Edition (Lexham Press, 2018).

Textual Criticism of the Bible: Revised Edition (Lexham Methods Series)

Save $7.50 (30%)

Price: $17.49

-->Regular price: $24.99

Suggested resources on textual criticism & the transmission of scripture

New Testament Textual Criticism: A Concise Guide

Save $4.50 (30%)

Price: $10.49

-->Regular price: $14.99

Old Testament Textual Criticism: A Practical Introduction, 2nd ed.

Save $9.60 (30%)

Price: $22.39

-->Regular price: $31.99

Encountering the Manuscripts: An Introduction to New Testament Paleography and Textual Criticism

Save $7.20 (30%)

Price: $16.79

-->Regular price: $23.99

Principles of Textual Criticism

Save $5.00 (40%)

Price: $7.49

-->Regular price: $12.49

A Student’s Guide to Textual Criticism of the Bible

Save $2.20 (20%)

Price: $8.79

-->Regular price: $10.99

Myths and Mistakes in New Testament Textual Criticism

Save $5.60 (20%)

Price: $22.39

-->Regular price: $27.99

Exploring the Origins of the Bible: Canon Formation in Historical, Literary, and Theological Perspective (Acadia Studies in Bible and Theology)

Price: $31.99

-->Regular price: $31.99

Mobile Ed: Michael Heiser How We Got the Bible Bundle (2 courses)

Save $224.99 (45%)

Price: $269.99

-->Regular price: $269.99

Related articles

4 Ways Textual Criticism Can Aid Bible Study

Why We All Need the Biblical Languages

The Greek New Testament: 3 Most Common Editions & Which You Should Use

5 Reasons Studying the Original Languages Is Worth the Pain

Original Language Research: What to Do, What Not to Do

3 weeks ago

37

3 weeks ago

37

English (US) ·

English (US) ·