If all the “gospel-centered” ministries were listed in one spot, I suppose Microsoft Excel itself couldn’t contain the list. Yet, to the surprise of some, there are different schools of thought on how to describe precisely what the gospel is.1

A discussion has been circulating about whether one should focus on the gospel as an announcement of victory with kingship concepts being paramount, or if one should center more on soteriology, such as law-court images like justification. In this article, I will seek to diagnose why this conversation regularly suffers from miscommunication. I will argue that both perspectives need one another.

The Scriptures bring these realities together, so we shouldn’t divorce them. The gospel is as deep and rich as it is simple and straightforward.2

Different but compatible emphases

These discussions surrounding the gospel relate to various emphases. Those who speak of the gospel as a kingly announcement of victory typically focus more on the four Gospels through the prism of biblical studies. Attention is especially given to the cosmic and communal dimensions. In other words, they often argue we need to start with the Gospels and Jesus’s definition of the term. They also rightly do more historical work on how the term εὐαγγέλιον was used in antiquity, noting its political context.

On the other hand, those who emphasize the centrality of justification by faith typically tend to begin with Paul and approach things from a more systematic theology perspective. Often the gospel is described employing the “Romans Road” and Pauline categories. Here, the gospel is more personalized and focused on the individual, emphasizing the need for faith and repentance and the righteousness that Christ gives his people.

Those in the former camp agree that justification is an important concept in the Scripture but sometimes describe it as a benefit of the gospel rather than a part of the gospel itself. Those in the latter camp will speak of how an announcement of a king’s victory is not good news unless one is “incorporated” into the rule of the king making the announcement. A king’s victory is bad news for those opposed to his reign.

A way forward? Prophet, priest & king

I think both perspectives need one another. To put this another way, we shouldn’t pit Jesus against Paul, or biblical studies against systematic theology. These are different angles on the same reality. Paul and Jesus (and biblical studies and systematics) are already integrated. We just need to do more work to see that reality.

Perhaps one way to combine the multifaceted nature of the gospel is by looking at it through the messianic categories of prophet, priest, and king.

In one sense, those who work in the field of biblical studies might recoil at this trifold perspective because it leans more toward dogmatic categories. However, the trio is also a reflection on what it means for Jesus to be the Jewish messiah. In this way, these categories might move the conversation forward by integrating a first century context with a systematic overlay to help us understand the hopes of Israel.

My argument is that the gospel is a prophetic message involving a priestly mechanism with a kingly goal; namely, the arrival of God’s kingdom.

Prophet: proclaiming the message of God’s reign

We can begin with the category of prophet. Prophets proclaimed the word of God. They were truth-tellers, delivering messages from God.

This lens then highlights how the gospel is a message, an announcement. The gospel is not first a command or even a doctrine, but the communication of an event. The prophetic lens is important for defining the gospel because εὐαγγέλιον is first and foremost a message.

The gospel is not first a command or even a doctrine, but the communication of an event.

However, more can be said because it is a message of good news. The Greek word itself is the compound form of the adverb εὖ (“well”) and most likely the noun ἄγγελος (“messenger”) and has its Hebrew corollary in the term בָּשַׂר (bāśar). The gospel is thus a message that brings glad tidings.

In the Old Testament, prophets are the mouthpieces of God, proclaiming his word. When Moses is called, he hesitates because he is not eloquent of speech, but God tells him he will speak through him (Exod 4:10–12). When the Lord calls Samuel, “the Lord was with him and let none of his words fall to the ground” (1 Sam 3:19). Burning coals touch Isaiah’s mouth and he is told to “speak” God’s words to the people of Israel (Isa 6:6–9). The Lord speaks to Jeremiah, saying he knew him and consecrated him before he was born to be a prophet. But Jeremiah responds, “I don’t know how to speak, for I am only a youth” (Jer 1:5–6). God replies that whatever he says, Jeremiah will speak—and he touches his mouth and gives him words (Jer 1:7–9). Likewise, Ezekiel is sent to a nation of rebels and told to speak the words of the Lord (Ezek 2:3–4).

The portrait of a prophet therefore must begin with their speaking vocation. Prophets spoke messages of both hope for Israel and doom if they neglected the covenant with Yahweh. They pronounced blessings if they stayed loyal among the nations, but woes if they began to worship the gods of other nations.

More specifically, we can turn to the Old Testament and find that the prophets announced the good news of God’s reign for God’s people. Probably the most important context for the NT use of εὐαγγέλιον comes from the Prophet Isaiah. Isaiah employs the term with respect to the coming reign of Yahweh and the return from exile.

See uses of “gospel” in the Greek translation (LXX) of Isaiah.

Zion and Jerusalem are to proclaim the “good news” of God’s return to establish his rule, which is further described as Yahweh shepherding his people (Isa 40:9–11). The prophet also declares the bloodied and dusty feet of those who carry good news are beautiful because they proclaim peace, salvation, and tell that God reigns (Isa 52:7). Isaiah 52:7 parallels the good news with God’s reign which brings peace and salvation. In Isaiah 61:1, the anointed one announces the Spirit of Yahweh is upon him to bring good news, which is further defined as “binding up the brokenhearted, proclaiming liberty to the captives, the opening of the prison to those who are bound.” The Isaianic gospel, therefore, pertains to Israel’s national salvation through their messiah who will return them to their land and restore the fortunes of their kingdom.

In summary, beginning with Jesus’s messianic vocation of prophet helps us remember the gospel is an announcement of glad tidings that communicates the arrival of God’s reign.

Priest: substituting himself on behalf of humanity

However, in all this we can’t separate Jesus’s vocation as a prophet from his vocation as a priest. Again, many descriptions could be given of a priest, but here I will focus on how priests act on behalf of humanity by offering gifts and sacrifices to God (Heb 5:1).

Though priests serve in various capacities, essentially priests attend or serve in God’s house for humanity. They maintain the edifice of the house of God on behalf of God’s people. As they maintain this house for God, they enter God’s presence representing, mediating, and interceding for God’s people. The priests are those who “come near to the Lord” (Exod 19:22).

Priests offer gifts and sacrifices. Offerings are the specific and exclusive actions priests perform as human beings for the sake of human beings but before God. Priests don’t enter the presence of God without offerings. The first explicit priest mentioned in the Bible is Melchizedek, who brings out bread and wine to Abraham (Gen 14:18–20). Priests would kill animals before the Lord and bring the blood before the Lord (Lev 1:5, 11, 15). They would bring flour, oil, and grain and burn it as a memorial portion on the altar (Lev 2:2, 9). Priests were the ones to restore the altar (Ezra 3:1–7), celebrate the Passover (6:19–22), and offer evening sacrifices (9:4–5).

All of this becomes important as we return to Isaiah’s context, where he gives us a description of the gospel. While we can say the gospel is the announcement of God’s reign, Isaiah speaks more specifically about how this reign will be accomplished. He affirms it is Yahweh’s servant who will accomplish this, and he will do so by offering himself.

While priests offered animals, Jesus offered himself, thus acting as the priest and the sacrificial offering. And in so doing he “sprinkles the nations. Kings will shut their mouths because of him” (Isa 52:15). He “bore our griefs and carried our sorrows” (53:4), he was “pierced for our transgressions; crushed for our iniquities … by his wounds we are healed (53:5). “Like a lamb he was led to the slaughter” (53:7), “stricken for the transgression of his people” (53:8). His soul was an offering for guilt (53:10), and by his sacrifice “many are accounted righteous” (53:11).

Isaiah combines kingship and priestly themes under the banner of the gospel, as the messiah is a priest–king. Those who wish to emphasize kingly motifs in the gospel should not do so at the expense of priestly motifs. Paul highlights the judicial aspect of the gospel because Isaiah does. Justification is not just a benefit of the gospel, but how the message of God’s reign becomes good news.

Paul explains this most fully in Romans. He affirms, as his thesis, that “the gospel is the power of God for salvation … for in it the righteousness of God is revealed” (Rom 1:16–17). This raises the question of what the righteousness of God is and how it is revealed. The rest of Romans provides the answer.

The good news must begin with the bad news that everyone is unrighteous, both Jews and Gentiles (Rom 1:18—3:20). However, the righteousness of God has now been revealed in the work of God. Jesus became an atoning sacrifice for his people so that they might be declared righteous (justified), and God might still be righteous in punishing sin (Rom 3:21–31).

The imagery Paul employs at this point is both priestly and legal. God is the righteous judge who punishes sin, but Jesus is the priest and the lamb who took that sin upon himself and therefore received the punishment for others. As Isaiah said, he was stricken for the transgression of his people, and thus many were accounted as righteous.

The only way to receive this gift is by faith, receiving what God has done on your behalf. Paul argues this has always been the case, for Abraham was not justified by what he did but by believing (Rom 4:1–25). God didn’t view Abraham as righteous because he was circumcised, but because he trusted God’s word. Abraham was declared righteous before he was circumcised, with circumcision as a seal of the righteousness that was already his. The way, therefore, to be incorporated into the messiah and receive the benefits of the king, which is a declaration of right standing, is by faith.

Likewise, Paul closely connects, or even equates, the gospel with justification in Galatians when he says, “And the Scripture, foreseeing that God would justify the Gentiles by faith, preached the gospel beforehand to Abraham” (Gal 3:8).

Paul’s point in both cases seems to be that the gospel can’t be understood without the priestly dimension. In this sense, while the gospel can’t be reduced to justification by faith (a mistake some make), it is also true that the gospel isn’t good news without justification (a mistake others make). The gospel must include Christ’s priestly work.

While the gospel can’t be reduced to justification, it is also true that the gospel isn’t good news without justification.

King: realizing God’s reign

Finally, we can’t neglect the kingly dimension of the gospel. Too often in certain descriptions of the gospel, the reality of Jesus’s kingly task and his kingdom are curiously absent. A personalized account of the gospel can neglect its inherent political and communal dimension.

Εὐαγγέλιον is a media term—a message of good news. But if it is the message of God’s reign, then it is a dispatch of victory, and thus a kingly or political announcement. This reality is confirmed when one sees that the term “gospel” is traditionally used in political contexts.

In the OT, the term “gospel” is usually connected with some sort of political or military context. In 1 Samuel 31:9, the Philistines cut off Saul’s head and send the “good news” to all the Philistines. In 1 Kings, Adonijah expects to hear “good news” from Jonathan in relation to his kingship (see 1 Kgs 1:42 [3 Kgdms 1:42 LXX]) but ends up hearing that Solomon has been anointed as king (1 Kgs 1:46). In 2 Kings 7:9 (4 Kgdms 7:9 LXX), the good news refers to the flight of the Arameans.

The Psalms continue this designation when David speaks of the good news of righteousness (Ps 40:9 [39:10 LXX]). Though this could be interpreted in a more individual or personal way, Yahweh saves and delivers David the king and therefore the nation. Women tell the good news of kings fleeing before Israel in Psalm 68:11 [67:12 LXX], and the whole earth is to proclaim the good news of his salvation in the context of Yahweh reigning in Psalm 96:2 [95:2 LXX].

The prophets also use the word “gospel” in the context of political and military victory—or at least its promise. In Joel 2:32, the prophet tells of the day when everyone who calls on the name of Yahweh will be saved. The LXX of Joel 2:32 describes this as “good news” (ευαγγελιον). In Nahum, “good news” is employed in the context of the defeat of Assyria’s king, allowing those in Judah to celebrate their festivals (Nah 1:15).

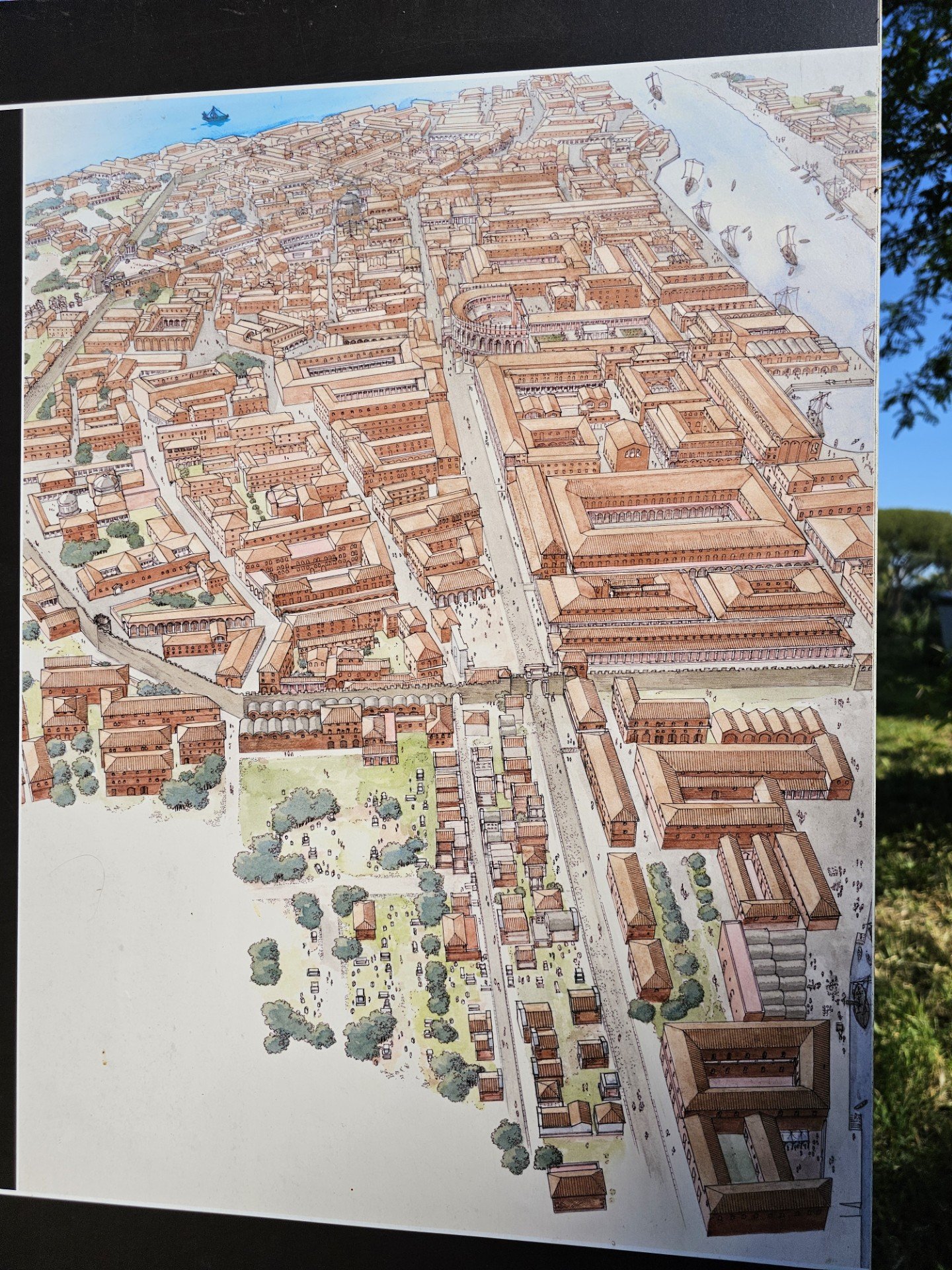

Though there are a few references that fall outside of the normal political and militaristic contexts, the majority of settings pertain to kings, battles, and victories. What readers will find is that a similar phenomenon occurs in the Greco-Roman background to the term. News of a ruler’s birth, coming of age, enthronement, speeches, decrees, and acts are all put under the banner of “good news.” A Priene calendar inscription from 9 BCE speaks of the birth of the emperor Augustus as “the beginning of good news” for the world:

Augustus has made war to cease and … put everything in peaceful order; and whereas … the birthday of our God signaled the beginning of Good News for the world because of him.3

In one inscription, it states that the day when a son of Augustus takes on the toga is “good news for the city.” A papyrus letter from an Egyptian official in the third century AD uses the term in connection with the accession of Emperor Julius Verus Maximus. And an inscription at Amphiareion of Oropos from around 1 CE mentions the “good news of Rome’s victory.”

For all the Evangelists, “gospel” language is a political announcement of victory, specifically about how the Yahweh’s anointed one will bring God’s reign to the earth. Matthew only employs the term a few times, but he ties it to the political reality of Jesus’s announcement of the kingdom (e.g., 4:23; 9:35). Mark labels his entire work “a gospel” because it is about Jesus’s life, death, and resurrection (Mark 1:1). Like in Matthew, the message of Jesus concerns, “the gospel of God” that requires a response (Mark 1:14–15). Luke is drawn to the verbal form (εὐαγγελίζω). He employs the phrase as a summary of the teachings of Jesus (4:43; 7:22; 8:1; 20:1), John (3:18), and the disciples (9:6). Acts shows the gospel of the kingdom was the content of the early church’s preaching (Acts 5:42; 8:12, 25, 35, 40; 10:36; 11:20; 13:32; 14:7; 14:15, 21; 15:7, 35; 16:10; 17:18; 20:24). Now the focus is on the king of the kingdom (5:42; 8:12, 25, 35; 10:36; 11:20; 17:18).

Conduct your own study in Logos on topics like the gospel.

Therefore, we must not neglect the kingly and political aspects of the gospel. One of the ways I’ve seen this occur is the lack of emphasis in gospel presentations on the resurrection, ascension, and return of Christ. These are just as integral to the gospel as Jesus’s death and justification. Too often Jesus’s exaltation is bypassed as an “extra” that is not necessary to a gospel explanation. However, these realities should be incorporated in descriptions of the gospel because they are where the king is crowned.

Conclusion

So what is the gospel? As Paul says, it is an announcement of Jesus the Messiah who has died and been raised (1 Cor 15:1–4). And as I’ve argued, we can get a balanced perspective of this important reality by examining it through the lens of Jesus’s role as prophet, priest, and king (which are inherently integrated):

- The prophet lens reminds us gospel is a “media” term and concludes it is an announcement of God’s reign.

- The priestly lens reminds us that God’s reign is only good news for those who are incorporated into this reign by the Suffering Servant who gave his life as ransom for many and thus justified his people.

- The kingly lens reminds us this announcement is a political one that concerns the kingdom of God, and Jesus’s death, resurrection, and ascension are the means by which Christ becomes king.

One accepts this message of glad tidings by faith and repentance.

My hope is that this perspective can reconcile various views on the gospel and help people from both sides realize that some differences are a matter of emphasis rather than content. The gospel needs to be declared in all its proportional dimensions, or else it can be distorted by anybody’s preference for one bit or the other. We don’t have to pit Jesus against Paul or biblical studies against systematic theology. Through integrating them, we get a full picture of the gospel message that has outlasted empires and emperors and will continue to be proclaimed until Christ returns.

What exactly is the gospel? Enter the debates with these resources

What Is the Mission of the Church? Making Sense of Social Justice, Shalom, and the Great Commission

Save $5.25 (35%)

Price: $9.74

-->Regular price: $14.99

The King Jesus Gospel, Revised Edition: The Original Good News Revisited

Save $5.10 (30%)

Price: $11.89

-->Regular price: $16.99

Gospel Allegiance: What Faith in Jesus Misses for Salvation in Christ

Save $0.90 (5%)

Price: $17.09

-->Regular price: $17.99

Beyond the Salvation Wars: Why Both Protestants and Catholics Must Reimagine How We Are Saved

Save $1.10 (5%)

Price: $20.89

-->Regular price: $21.99

The Crucified King: Atonement and Kingdom in Biblical and Systematic Theology

Save $8.10 (30%)

Price: $18.89

-->Regular price: $26.99

Five Views on the Gospel (Counterpoints: Bible and Theology)

Save $1.00 (5%)

Price: $18.99

-->Regular price: $19.99

Four Views on the Church’s Mission (Counterpoints)

Save $5.10 (30%)

Price: $11.89

-->Regular price: $16.99

Related articles

- Christ Crushed for Us: The Gospel in Isaiah 53

- Law & Gospel: How Martin Luther Wanted You to Read Your Bible

- Finding (& Sharing) Jesus on the Romans Road to Salvation

- The Kingdom of God: The Great Unfolding Drama of Salvation

3 weeks ago

45

3 weeks ago

45

English (US) ·

English (US) ·