A longtime Christian and student of the Bible posted the following comment about Romans 8:1:

View the difference in versions here! You may want to add this to your NIV. I have an NIV Bible, but when I study, I always compare it to the KJV:

“Therefore, there is now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus” (Rom 8:1 NIV).

“There is therefore now no condemnation to them which are in Christ Jesus, who walk not after the flesh, but after the spirit” (Rom 8:1 KVJ).

Big difference, huh?

This comment concerns an issue that surfaces throughout the Bible: differences in Bible versions that may affect the meaning. While some Bibles include footnotes to indicate when such differences exist, these notes are not always helpful for readers with no background knowledge of the preservation and transmission of the Bible from its original authors to the current day.

What should we think when we find disagreement between English versions? Which translations are right? Why would translators “change” the biblical text? How can readers make good decisions about these discrepancies between versions?

These questions are important for every student of the Bible, and textual criticism contributes part of the answer. In this article, we will describe what textual criticism is and why it is necessary. We will consider the goal of textual criticism as well as the benefits and limitations of the discipline.

If you have studied biblical languages and are familiar with textual criticism, we hope to refresh your knowledge and further develop your ability to take on some textual issues in your ministry. If you have never studied Hebrew or Greek and are unfamiliar with textual criticism, this article aims to introduce you to a new world. It will equip you to study and teach the Bible more effectively by explaining why English versions differ while helping you decipher footnotes that indicate variations in word choice. Finally, we hope to increase your awareness of the challenges faced by biblical scholars in their work with the text and increase your appreciation for the text that has been so carefully preserved for us.

Table of contents

- The difference between translation and textual criticism

- What is textual criticism?

- Why is textual criticism necessary?

- How can familiarity with textual criticism help me understand my Bible?

- With such textual differences, are our Bibles reliable?

- How does Old Testament and New Testament textual criticism compare and differ?

- What different forms of biblical manuscripts do we have?

- What manuscript witnesses do we have?

- What is the goal of textual criticism?

- What are the limitations of textual criticism?

- Glossary of key translation and textual criticism terms

- What are resources on Bible translation?

- What are resources on textual criticism?

The difference between translation and textual criticism

We first note that translation issues are not textual issues. Textual criticism can explain some of the differences people notice between their English versions, such as the omission of “who walk not after the flesh, but after the Spirit” in the NIV of Romans 8:1 above. However, other variations in translation are not text-critical in nature; instead, they reflect translation techniques and decisions made by committees. Understanding the differences between text-critical issues and translation issues is an important first step in the study of textual criticism because it helps explain why translations differ. It also helps us determine when textual criticism will not be helpful.

Translation issues are concerned only with transferring a particular passage from the source language into the target language. In an analogy from the world of education, teachers are like translators. Using textbooks and other resources, teachers try to find the best possible way to translate (transfer) the information to their students. The teachers’ primary concern is not establishing the validity of their resources; they have placed trust in scientists, linguists, mathematicians, and historians—the experts who are continually updating and adjusting the information in textbooks. The teachers’ primary concern is communicating the text to their students effectively. In this way, translators are like teachers: those who communicate the meaning of the text. Meanwhile, textual critics are like scholars: the experts who establish the sacred text.

What is textual criticism?

The word “criticism,” which today carries a negative connotation, derives from an older usage meaning “to analyze or investigate.” Textual criticism involves analyzing the manuscript evidence in order to determine the oldest form of a text. Such analysis also reveals historical evidence about the transmission of the text, scribal habits, theological biases, and more. Biblical scholars engage in this discipline, as do scholars in the broader field of literature. For example, you often see “critical editions” for the works of authors like Plato or Shakespeare: a critical edition is simply an edition of a text based on the earliest manuscripts and fragments available.

Because the original biblical manuscripts (called autographs) have not survived, we must depend on later copies, none of which agree with each other 100 percent. The task of the textual critic is to resolve variations in the readings of these ancient manuscripts by identifying and “removing all changes brought about either by error or revision.”1 When successful, textual criticism results in the best representation of the Ausgangstext, or the ancient form of the text that is the ancestor of all extant copies, the beginning of the manuscript tradition.

Why is textual criticism necessary?

The Bible was written at a time when the means for sharing documents was far different from the technology we have today. When the Church of Thessaloniki received a letter from the Apostle Paul in the mid-first century, the believers there would have read it aloud in their gatherings, and then devoted followers who recognized the value of Paul’s words would have produced handwritten copies of the letter to pass around to a wider audience. By the end of the first century, Paul’s letters were being copied as a collection. Hand-copying of the Pauline corpus continued through the centuries until Johannes Gutenberg invented moveable type in fifteenth-century Germany. With some variation, every book in the Bible has been subject to this process of repeated hand-copying—the New Testament books in Greek, and the Old Testament books in Hebrew and Aramaic.

In addition to these original language manuscripts, Christians translated their sacred texts into other languages. The Old Testament documents were translated into Greek, Latin, Coptic, and Syriac, and the New Testament documents were translated into Latin, Coptic, and Syriac, followed later by Gothic, Armenian, Georgian, Ethiopic, Slavonic, and Arabic. The Bible was repeatedly recopied within each of these languages. Further, Jewish and Christian scholars quoted the sacred texts in their own writings, which others also copied and translated to dispense and preserve.

This proliferation of hand-copied texts resulted in thousands of manuscripts, no two exactly alike. In textual criticism, these variations in the wording of the ancient manuscripts are called variation units, and each different reading at that point is called a variant.

How can familiarity with textual criticism help me understand my Bible?

Familiarity with the process of textual criticism can help make sense of marginal notes that appear in many English versions.

For example, returning to Romans 8:1, we see that the footnote for Romans 8:1 in the ESV says, “Some manuscripts add who walk not according to the flesh (but according to the Spirit).” This footnote points out a place in the text where there is variation in the wording of the ancient manuscripts.

Logos’s Guides include Apparatuses and Textual Commentary sections to aid your textual criticism work.

With such textual differences, are our Bibles reliable?

Though there are thousands of variation units in the text of the Bible, the text is remarkably stable. Old Testament scholar Bruce Waltke says the most recent critical edition of the entire Old Testament (BHS) has no significant variation in 90 percent of the text.2

Of the thousands of instances of variation in the Bible, nearly all of them concern spelling, word order, synonyms, and other elements that do not affect meaning at all. Those variation units that affect the meaning of a biblical text are found in the footnotes of any good English Bible, but even these variants do not affect doctrine or theology.3

How does Old Testament and New Testament textual criticism compare and differ?

The types of variation that appear in biblical manuscripts share important similarities, regardless of which Testament the textual critic is working in. Thus, both Old Testament (OT) and New Testament (NT) textual critics can follow the same general process when determining which variant readings are the most accurate. However, the textual evidence for each Testament is quite different. Basic knowledge of these differences establishes the groundwork for understanding the task of the textual critic.

The OT developed over a long period and is largely silent on matters of authorship, audience, purpose, and time of writing. By contrast, the documents of the NT were written during a period of less than one hundred years, and many books explicitly identify authors, audiences, and even the reason for composition. Based on historical knowledge of the first and second centuries, scholars can also make reasonable assumptions about the date of most NT books.

Another significant difference between the Testaments that concerns the textual critic is the quantity and quality of manuscripts available.

What different forms of biblical manuscripts do we have?

Many of the available biblical manuscripts are in codex form. The codex is the predecessor of the modern book—sheets of papyrus or parchment were folded in half and sewn together along the fold. Both sides of the page were used for writing. Thus, fragments of a manuscript may only represent part of a page from a codex, so the text on one side may be near the beginning of a chapter, while the text on the other may be later in the same chapter or come from a different chapter altogether. The codex format is known to have existed by the late first century AD (from a reference by the Roman poet Martial, c. AD 85), but it was not widely used until the fourth century.4

The other usual format for ancient biblical manuscripts was the scroll, a long roll of papyrus or parchment with text written in columns. A scroll could be quite long and had to be read by unrolling the next column and rolling up the finished column.5 For these reasons (and others), scrolls usually had text on only one side.

What manuscript witnesses do we have?

Old Testament witnesses

If some OT writings date as far back as Moses, then parts of it were copied by hand for almost three thousand years before the printing press appeared.

One challenge for OT textual critics is that few fragments of any early writings have survived. Two small scrolls dating to the sixth or seventh century BC contain a version of the priestly blessing found in Numbers 6:24–26, but this provides limited material for textual critics.6

A second challenge for OT textual critics is that the few available manuscripts appeared much later after the original writings. For most of the history of biblical scholarship, the oldest and best available manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible dated to the tenth and eleventh centuries AD—far removed from the original writing. The Leningrad Codex (AD 1009) is the only complete manuscript of the Hebrew Bible, but the Aleppo Codex (AD 925), the Cairo Codex of the Prophets (AD 896), and others contain significant portions.

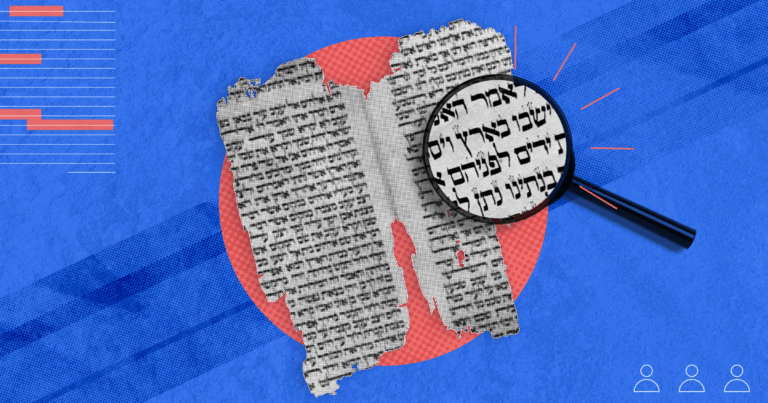

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1947 revolutionized the study of OT textual criticism when Hebrew manuscripts from as early as the first century BC surfaced. However, even these manuscripts are a considerable distance from the original writing of the OT books.

Important Hebrew Manuscripts:

|

Name |

Date |

|

Biblical texts from Qumran (Dead Sea Scrolls) |

c. 100 BC |

|

Cairo Codex of the Prophets |

AD 896 |

|

Aleppo Codex |

AD 925 |

|

Leningrad Codex |

AD 1009 |

New Testament witnesses

Unlike the OT manuscript evidence, which is meager and far removed from the actual composition of the books, the NT has thousands of surviving manuscripts, many of which were copied within three centuries of when the books were written.7 A few can even be safely dated as early as the mid-second century.8

The NT manuscripts also exhibit greater textual variation than their OT counterparts, in part because of the historical setting of their transmission. Bruce Metzger explains,

In the early years of the Christian Church, marked by rapid expansion and consequent increased demand by individuals and by the congregations for copies of the Scriptures, the speedy multiplication of copies, even by non-professional scribes, sometimes took precedence over strict accuracy of detail.9

In addition, scholars have discerned that manuscripts often share typical variant readings and have sorted them into textual groupings, labeled the Alexandrian text-type, the Byzantine text-type, the Western text-type, and the so-called “Caesarean” text-type.

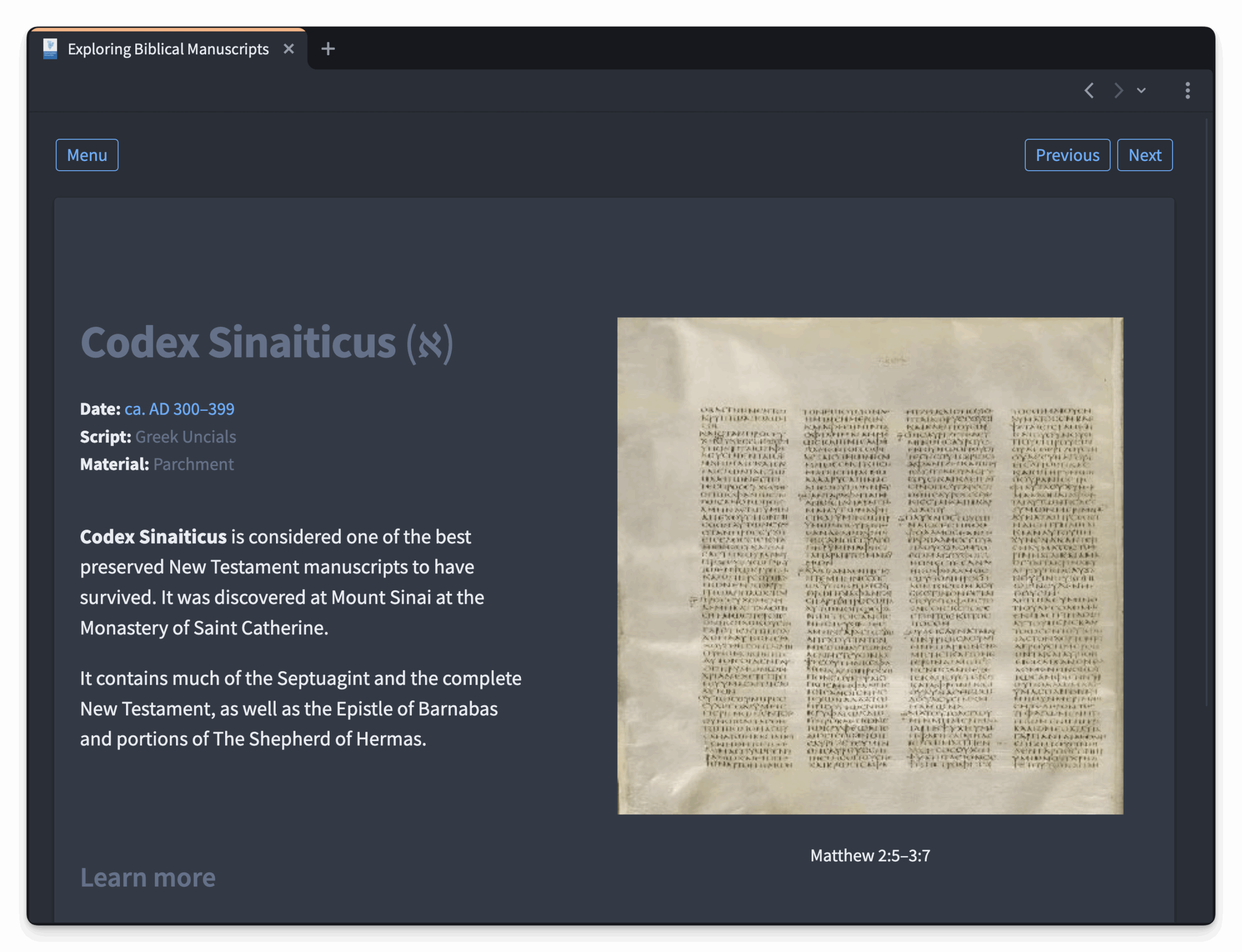

Logos’s Exploring Biblical Manuscripts interactive provides a visual guide to learn about Old and New Testament witnesses.

What is the goal of textual criticism?

The main goal of earlier textual criticism was to establish the original reading of the biblical text. The terminology of “original” text is now seen as problematic because textual critics have recognized the complexity of the writing and “publication” process in ancient times.10

For New Testament textual criticism

However, the goal of establishing the Ausgangstext (the earliest form of the text from which all extant copies descend) is feasible for the New Testament since we have an abundance of manuscripts copied shortly after the autographs themselves were written.11

The primary complication for NT textual critics is deciding between the many copies and variant readings of the NT. Yet, as Wegner notes,

The plethora of New Testament manuscripts is a great benefit when trying to determine the original reading of the New Testament, for it is easier to sift through and evaluate the various extant readings than to emend texts with no evidence.12

A further goal of NT textual criticism that is pursued by current textual scholars is the history of the transmission of the text, a study that has valuable implications for students of history, exegesis, and theology.13

For Old Testament textual criticism

The situation is more complicated for the Old Testament. Most scholars recognize that the OT underwent modifications during the long process of its formation. Wegner cites three examples for which “even the most conservative scholars must allow for some modification of the original texts”:

- The reference to “Dan” in Genesis 14:14

- The account of Moses’ death in Deuteronomy 34

- The phrase “and within yet sixty-five years Ephraim will be shattered from being a people” in Isaiah 7:814

But the lines between the original author’s composition, the editorial work of scribes, and the “simple” copying of final manuscripts are blurry. Unlike the majority of NT textual critics, the OT textual critic has to decide exactly which stage of the OT composition or transmission is the goal.

The goal of OT textual criticism we adopt is to reconstruct the text’s “final literary product.”15 This final form developed during a complex and irretrievable compositional history. At whatever point it reached its final authoritative status, the text then stood at the beginning of an equally long transmission history.

For some books or sections of the OT, there were apparently several valid “final forms” of the text. Such is the case with the book of Jeremiah, which is significantly longer and arranged differently in the Hebrew of the Masoretic Text from in the Hebrew Vorlage that stands behind the Septuagint.16 Thus, rather than deciding which version of Jeremiah is “right,” textual critics should try to determine the final form from which the Septuagint developed and the final form from which the Masoretic Text (and thus, the English Bible) developed. This goal is similar to reconstructing the Ausgangtext since both focus on finding the text that gave rise to the known textual variants.

Logos’s OT, LXX, and NT Manuscript Explorer provide databases on extant manuscripts along with links to view them.

What are the limitations of textual criticism?

Textual criticism serves an important role in the study of the Bible. People who value the Bible as God’s Word should be interested in the earliest wording of the text, and textual criticism helps answer this question.

But it cannot answer everything we want to know. For example, it may be able to determine that Mark 16:9–20 and the story of the adulterous woman in John 8 are not original to the works of Mark and John, but it cannot say whether these added texts are inspired. It cannot tell us who wrote the Pentateuch or the letter to the Hebrews, and it cannot detail the process of how the Bible came together. Textual criticism cannot speak to the historicity of every story or the reason for conflicting accounts.

Many of these questions are considered by scholars working in other areas of biblical criticism such as canonical criticism, form criticism, historical criticism, redaction criticism, and source criticism. But textual criticism must be the starting place for all biblical study because it works to establish the very text of the Bible used for further research.

Textual criticism must be the starting place for all biblical study because it works to establish the very text of the Bible used for further research.

Glossary of key translation and textual criticism terms

- Textual criticism: The process of evaluating variants in the biblical text to determine which reading was likely the earliest.

- Textual critic: A scholar who examines variants in the biblical text to determine the most authentic readings.

- Autograph: The original manuscript or document of a writing. The Greek word autographos literally means “written in one’s own hand.” No autographs of biblical books have survived.

- Scribe: A copyist or writer who copied texts prior to the invention of the printing press.

- Variant: A term of textual criticism describing the different wording of one text when compared with another; also called a variant reading.

- Variation unit: A place in the text where there is variation in the wording of the ancient manuscripts. A specific different reading in a variation unit is called a variant.

- Witness A particular manuscript, translation, or quotation that is cited as evidence of a variant reading in a variation unit.

- External evidence: Manuscript evidence in textual criticism that relates to the age, grouping, quantity, and distribution of the biblical manuscripts.

- Internal evidence Manuscript evidence in textual criticism that relates to the habits of scribes and the stylistic and theological bent of the author.

- Text-type The older term for a grouping of NT manuscripts based on their similarity of text; the term is thought by many current textual critics to be misleading because it implies clearer boundaries than actually exist between the groupings. The names of the “text-types” (Alexandrian, Byzantine, Western, or Caesarean) are typically still used in text-critical discussions, but they are called groupings, streams, or traditions.

- Family: A group of manuscripts that are so closely related that it is possible to create a family tree, called a stemma, showing how they all descend from a common textual ancestor.

- Dead Sea Scrolls: A large collection of ancient Jewish manuscripts found in caves on the northwest end of the Dead Sea at various times between 1946 and 1956. These texts in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek date from 250 BC to AD 70. They represent the oldest existing copies of the OT (including almost all OT books) and include religious texts outlining the practices of a Jewish sect.

- Ausgangstext: German for “beginning text” or “start text”; sometimes translated as “initial text.” This term is used in NT textual criticism to reflect the process of examining all variant readings for a variation unit, and discerning which reading is the starting point for all of them.

- Source language: The language of a text being translated.

- Target language: The language of a text being produced from a text in another language (source language).

- Masoretic Text: Refers to any Hebrew text of the OT preserved by the Jewish scholars known as Masoretes in the early medieval period. This standard Hebrew text of the OT is abbreviated as MT and is usually based on the copy from the Leningrad Codex, the oldest complete Masoretic manuscript and dating from AD 1009.

- Septuagint: The Greek translation of the Hebrew Old Testament (Genesis–Malachi) begun around 250 BC. Sometimes abbreviated with the Roman numeral for seventy (LXX) based on the tradition that seventy translators participated.

- Critical edition: A printed biblical text created by textual critics that either primarily represents the text of a single manuscript (a diplomatic edition) or presents the best hypothetical original text of the Bible (an eclectic version); created by evaluating and selecting superior textual variants according to the standards of textual criticism; includes a critical apparatus detailing the variants and editorial choices.

What are resources on Bible translation?

Beekman, John, and John Callow. Translating the Word of God: With Scripture and Topical Indexes. Zondervan, 1974.

Beekman and Callow’s Translating the Word of God is a how-to manual for the serious translator, but it also includes information that can be helpful for understanding the difficulties of translation and the decisions translators make.

Duvall, J. Scott, and J. Daniel Hays. Grasping God’s Word: A Hands-On Approach to Reading, Interpreting, and Applying the Bible. Zondervan, 2020.

Duvall and Hays provide a helpful discussion of the inherent difficulties of translation in any language. They also explain and illustrate formally and functionally equivalent Bibles, as well as some that are periphrastic. Their work is a popular textbook for introductory hermeneutics courses.

Klein, William W., Craig L. Blomberg, and Robert L. Hubbard. Introduction to Biblical Interpretation. Zondervan, 2017.

This book includes a brief section on translation techniques. While their text covers the same basic content as Duvall and Hays, their treatment is shorter and includes fewer examples.

Nida, Eugene A. Toward a Science of Translating. Brill, 1964.

Eugene Nida was a pioneer in Bible translation theory and linguistics and is best known among Bible students for his joint project with Johannes Louw, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament Based on Semantic Domains. Nida is widely associated with the theory of dynamic equivalence.

What are resources on textual criticism?

The best resources for textual criticism vary in complexity. Some are designed for beginners, while others are written with the student of Greek or Hebrew in mind. Additionally, some resources deal with textual criticism for the entire Bible, but many focus on only the OT or the NT.

Black, David Alan. New Testament Textual Criticism: A Concise Guide. Baker Academic, 2006.

Black calls his guide “a simple and direct introduction” that “packages up … and delivers” countless workshops he has presented on the topic of textual criticism to pastors and laypeople. He overviews how and which errors occur, details the history of NT textual criticism, and illustrates the process on several NT texts.

Brotzman, Ellis R., and Eric J. Tully. Old Testament Textual Criticism: A Practical Introduction. 2nd ed. Baker Academic, 2016.

Brotzman’s book has been a standard introduction to OT textual criticism since its publication in 1994. In his endorsement on the back cover of the first edition, Waltke says the book brings together “an introduction to the Hebrew texts and versions, the theory of textual criticism, an introduction to BHS, and a sample of its practice.” With this second edition, Brotzman has collaborated with Eric J. Tully to update and expand the work to incorporate the latest research on the textual history of the OT.

Comfort, Philip. Encountering the Manuscripts: An Introduction to New Testament Paleography and Textual Criticism. B&H, 2005.

Comfort’s two-pronged study explores the role of scribes in the production of NT manuscripts.

McCarter, P. Kyle, Jr. Textual Criticism: Recovering the Text of the Hebrew Bible. Guides to Biblical Scholarship. Fortress Press, 1986.

McCarter’s introduction is succinct and filled with examples of OT text-critical issues. Part of a longstanding series of helpful guides to biblical scholarship, McCarter’s manual includes a glossary and a bibliography of primary sources, with descriptions of the textual characteristics of each biblical book.

Porter, J. Scott. Principles of Textual Criticism with Their Application to the Old and New Testaments. London: Simms and M’Intyre, 1848.

Porter’s introduction was the first of its kind in English. Most of his successors (e.g., Warfield, Robertson, Metzger) dealt exclusively with the NT, but Porter handled both Testaments. His book begins with a chapter on the “Object and Necessity of the Science,” in which he describes the extent of variation in the biblical manuscripts and the reasons for such variation. He notes that in light of these variations, textual criticism should be “exercised with due diligence, fidelity, and impartiality.”17

Wegner, Paul D. A Student’s Guide to Textual Criticism of the Bible: Its History, Methods and Results. InterVarsity Press, 2006.

Wegner’s introductory book is an excellent resource for a more detailed overview of textual criticism for both Testaments—though, as an Old Testament scholar, he is stronger in his treatment of the OT. He surveys the history of the discipline and its methods and discusses the goals and results of textual criticism. He also describes each kind of transmissional error and includes a chart summarizing the kinds of errors.

Textual Criticism of the Bible: Revised Edition (Lexham Methods Series)

Save $7.50 (30%)

Price: $17.49

-->Regular price: $24.99

Grasping God’s Word: A Hands-On Approach to Reading, Interpreting, and Applying the Bible, 4th ed.

Price: $49.99

-->Regular price: $49.99

New Testament Textual Criticism: A Concise Guide

Save $4.50 (30%)

Price: $10.49

-->Regular price: $14.99

Old Testament Textual Criticism: A Practical Introduction, 2nd ed.

Save $9.60 (30%)

Price: $22.39

-->Regular price: $31.99

Encountering the Manuscripts: An Introduction to New Testament Paleography and Textual Criticism

Save $7.20 (30%)

Price: $16.79

-->Regular price: $23.99

Principles of Textual Criticism

Save $5.00 (40%)

Price: $7.49

-->Regular price: $12.49

A Student’s Guide to Textual Criticism of the Bible

Save $2.20 (20%)

Price: $8.79

-->Regular price: $10.99

This article is adapted from Wendy Widder and Amy Anderson, Textual Criticism of the Bible, rev. ed. (Lexham Press, 2018).

Related articles

The Greek New Testament: 3 Most Common Editions & Which You Should Use

Why We All Need the Biblical Languages

Original Languages Is Worth the Pain

Original Language Research: What to Do, What Not to Do

Pastor, Are You Making These Common Lexical Mistakes?

4 days ago

17

4 days ago

17

English (US) ·

English (US) ·