The Great Commission serves as the church’s marching orders, which she does well to revisit.

Matthew’s Gospel closes with the resurrected Jesus appearing to the eleven disciples and declaring,

All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age. (Matt 28:18–20)

The so-called Great Commission closes the gospel narrative while initiating the mission of the church that would follow.

But it’s also powerfully evocative of earlier events, offering us a variety of frames for understanding the import of Jesus’s words. As we consider these frames, the nature of our Christian calling will come into crisper focus.

Table of contents

Jesus’s story as a mirror of Israel’s

The start of Matthew’s Gospel contains several elements that recall the book of Genesis.

- Its opening words (1:1)—“the book of the genealogy” (Βίβλος γενέσεως)—are only found in identical form elsewhere in Genesis 2:4 and 5:1, where they are used of the heavens and the earth and of Adam.

- Matthew then traces Jesus’s ancestry from Abraham (1:2–17).

- He tells us of a son of Jacob named Joseph, who had dreams (Matt 1:18–25; cf. Gen 37:5–11) and led his people into Egypt (Matt 2:13–15; cf. Gen 46:1–27).

We soon move into themes from the book of Exodus:

- A king kills baby boys (Matt 2:16–18; cf. Exod 1:15–22), from which Jesus, like God’s chosen deliverer, Moses, is spared (cf. Exod 2:1–10).

- Jesus and his family are called out of Egypt after a dream in which Joseph was told that those seeking Jesus’s life were dead (Matt 2:19–23; cf. Exod 4:19–20).

- Like Israel, Jesus passes through the waters of baptism (Matt 3:13–17; cf. Exod 14).

- Afterwards, he is led up by the Spirit into the wilderness, where he stays for forty days and is tested (Matt 4:1–11; cf. Israel’s forty years, Exod 16:35).

- He then teaches concerning the Law from a mountain (Matt 5–7; cf. Exod 19).

As Peter Leithart has argued, Matthew tells the story of Jesus in a way that purposefully mirrors the story of Israel, underlining the way in which the identity and destiny of the latter is fulfilled in the former.1

This pattern does not conclude with the end of Israel’s wilderness wanderings, but continues through the story of the conquest (e.g., Matt 10:1–23; cf. Num 13:1–20), the rise of the kingdom (e.g., Matt 12:1–8; cf. 1 Sam 21), the prophetic ministry of Elijah and Elisha (e.g., Matt 15:32–39; cf. 2 Kgs 4:42–44), and the fall of the kingdom and the exile that follows (e.g., Matt 26:50–66; cf. Jer 26). Jesus’s death is paralleled with the destruction of the temple and the fall of the kingdom to the Babylonians (e.g., Matt 27:39; cf. Lam 2:15–16).

A kingly, political declaration

Given this schema, it should not surprise us that the Gospel of Matthew concludes with verses that strongly recall the final verse of the Old Testament canon in certain orderings2 (2 Chron 36:23):

Thus says Cyrus king of Persia, “The Lord, the God of heaven, has given me all the kingdoms of the earth, and he has charged me to build him a house at Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Whoever is among you of all his people, may the Lord his God be with him. Let him go up.”

By framing Jesus’s statement (Matt 28:18–20) as he does, Matthew invites us to compare it to Cyrus’s declaration. There are doubtless similarities between the two.

- Both are commissions that serve as the final words of their respective books.

- Both Cyrus and Jesus begin by asserting that God has given them universal dominion.

- Both assure the commissioned parties that the divine presence is with them.

- Recognizing the character of the church as a living temple, we might draw a further parallel between Cyrus’s charge to build the temple and Jesus’s charge to preach the gospel.

In Isaiah 45:1, the Lord refers to the Persian emperor Cyrus as “his anointed” (literally his “Christ” or “Messiah”). The Lord’s establishment of Cyrus’s imperial dominion prefigures the universal rule of Jesus, the true King of kings and Lord of lords. The background in the charge of Cyrus should heighten our awareness of political overtones to its parallel in Matthew 28.

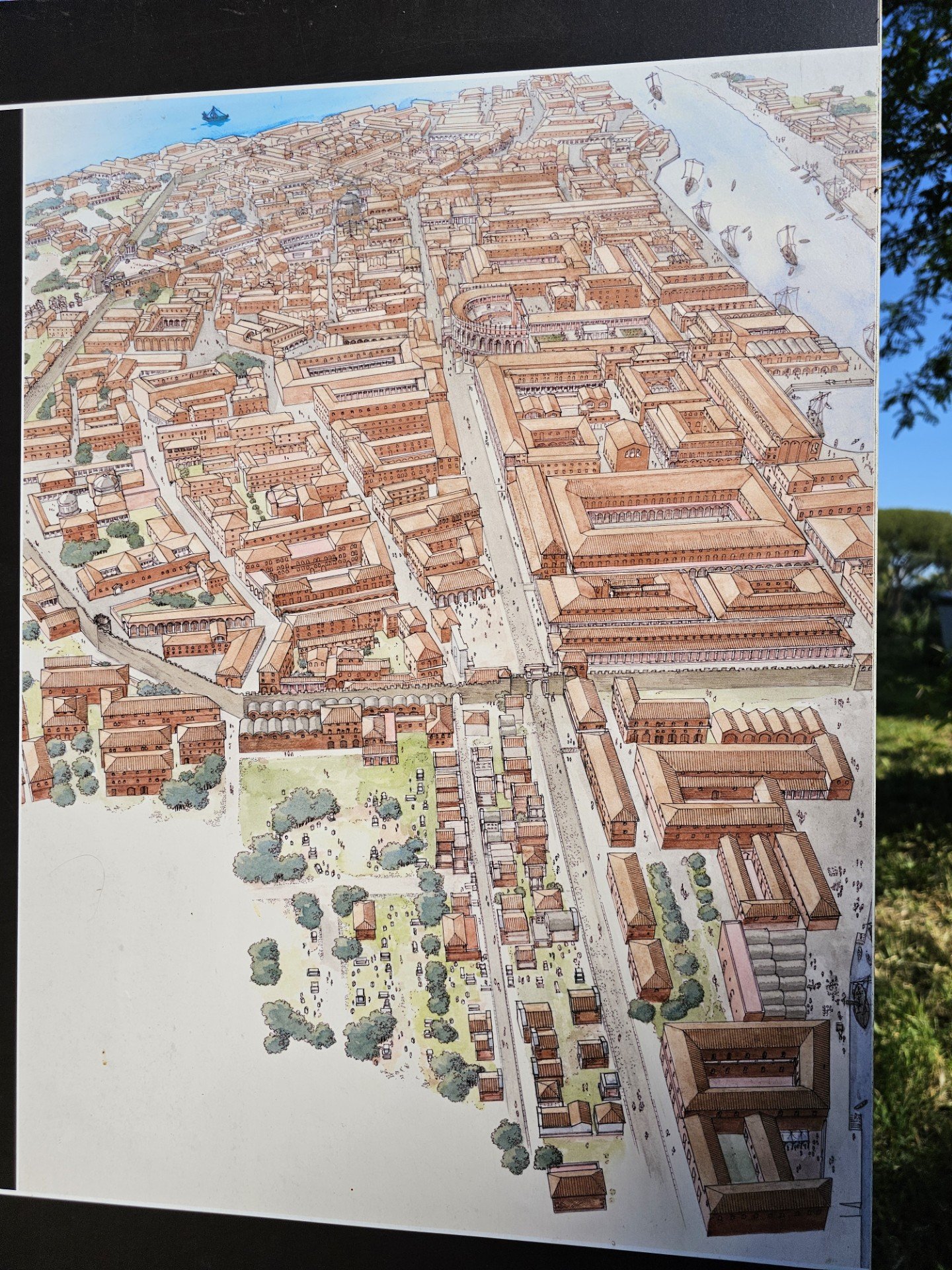

While Jesus’s instruction to “make disciples of all nations” chiefly refers to making disciples from all the nations, this reference to nations presents the comprehensive realm of the church’s mission with a particular aspect (see also Matt 24:9, 14; 25:31–32). Unlike the longer ending of Mark, which describes preaching the gospel to an undifferentiated “whole creation” (Mark 16:15), Matthew casts the church’s mission against the backdrop the world’s peoples, rulers, and empires to which we were introduced in Genesis 10 and 11. Jesus is not merely saving an indiscriminate group of individuals. He is asserting his lordship over all peoples, forming his own people among each of them.

Abram & the original commission

Our minds might also be drawn back to the initial call of Abram (Gen 12), which occurred in the shadow of the failed imperial project of Babel (Gen 11). In its city-building aspect, Babel was an attempt to gather humanity together as a single empire. In its tower-building aspect, Babel was an attempt to assert godlike human power, uniting heaven and earth under its sway. After God frustrated this project, he called Abram out of Ur of the Chaldeans, promising him that he would make his name great (Gen 12:2)—one of the aspirations that the Babel-builders had for themselves (Gen 11:4)—and that all nations would be blessed through him.

The call of Abram in Genesis 12:1–3 is the “great commission” with which the story of Israel begins:

Now the Lord said to Abram, “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. And I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and him who dishonors you I will curse, and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed.”

This commission calls Abram out from the nations, in particular from his fatherland and people, but promises that, through this initial separation, God will one day make Abram a blessing to all peoples.

God’s promise to bless the nations

There is an early occasion of this blessing later in Genesis, as, through Joseph’s wise administration of Egypt, many peoples are preserved during the seven years of famine (Gen 41). Joseph, presumed to be dead by his brothers and father, is in fact raised to the right hand of Pharaoh and given authority over the entire kingdom. When his eleven brothers visited, they bowed before him (Gen 43:26, 28; cf. Matt 28:16–17). After Joseph disclosed his identity to them—as one alive from supposed death—he gave them a commission (45:8–10):

God … has made me a father to Pharaoh, and lord of all his house and ruler over all the land of Egypt. Hurry and go up to my father and say to him, “Thus says your son Joseph, God has made me lord of all Egypt. Come down to me; do not tarry. You shall dwell in the land of Goshen, and you shall be near me, you and your children and your children’s children, and your flocks, your herds, and all that you have.”

Like Matthew’s, this commission begins with the assurance of a universal rule and the charge to bear good news to another (“Joseph is lord!”). However, it is primarily a call to “come” rather than to “go.” As Jacob and his family come to Joseph in Egypt, they will enjoy the presence of the beloved son that has seemingly raised from death.

Analyze the Bible’s intertextuality with Logos tools like the New Testament Use of the Old Testament.

Daniel’s “son of man”

Cyrus’s commission, with which the Old Testament closes, is, in certain respects, a reiteration of the calling of Abram. Now addressed not merely to one man and his household, but to Jews throughout his empire, Cyrus’s commission summons Jews to leave their current places of exile and return to their ancestral land. This occurs against the backdrop of a newly failed Babel project—Babylon.

Throughout its first half, the book of Daniel alludes to the story of Babel.

- After the defeat of Judah, its leaders are brought to the land of Shinar, the place where Babel was built (Dan 1:2; cf. Gen 11:2).

- The chapters that follow record a series of frustrated towering structures, which are also frustrated attempts to unite the peoples under a single human power. We encounter the great image of Nebuchadnezzar’s first dream broken by the stone cut without hands (Dan 2:31–35), the image of gold resisted by the three friends of Daniel (Dan 3:1–18), and the towering tree of Nebuchadnezzar’s second dream (Dan 4:10–17).

- We also witness a crisis of interpretation: the two dreams of Nebuchadnezzar (Dan 2:1–45; 4:4–27) and the writing on the wall (Dan 5:5–31), and frustrated language: the decree of Darius (Dan 6:6–9).

These allusions create the background for the prophetic vision of Daniel 7, where the figure of “one like a son of man” is given the rule that is stripped from the beasts. In verses 13 and 14, we read,

I saw in the night visions, and behold, with the clouds of heaven there came one like a son of man, and he came to the Ancient of Days and was presented before him. And to him was given dominion and glory and a kingdom, that all peoples, nations, and languages should serve him; his dominion is an everlasting dominion, which shall not pass away, and his kingdom one that shall not be destroyed.

It is to this that Jesus alludes in his statement before the Sanhedrin in Matthew 26:64. Jesus has the universal dominion foretold in Daniel’s vision. Or, as Richard Hays expresses it,

Daniel’s vision of Israel at last vindicated and ruling over the Gentile nations is to be enacted precisely through the disciples’ work of preaching and teaching. Their mission will instantiate the triumph of Israel’s God by extending his sovereignty over all the nations on earth. Integral to Matthew’s vision, however, is his insistence that the sovereignty of God over the nations will become effectual through nonviolent means. The nations are “conquered,” as it were, through baptism into the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit and through their instruction to obey the teachings of a master who has insisted that the meaning of the Torah is summed up in acts of love and mercy.3

The Psalter’s testimony

This dominion was also anticipated in the Psalms.

For instance, Psalm 2:7–9 states,

I will tell of the decree: The Lord said to me, “You are my Son; today I have begotten you. Ask of me, and I will make the nations your heritage, and the ends of the earth your possession. You shall break them with a rod of iron and dash them in pieces like a potter’s vessel.”

Likewise, Psalm 72 alludes to the calling of Abraham, presenting the universal dominion of the heir of David (“May all kings fall down before him, all nations serve him,” v. 11) as the way the universal blessing promised in Genesis 12 would be realized (“May people be blessed in him, all nations call him blessed,” v. 17).

God’s presence for Joshua-like conquest

The Great Commission further recalls the commission that the Lord gave to Joshua after Moses’s death.

- Joshua was charged to “be strong and very courageous” (Josh 1:6), going over the Jordan into the land and taking possession of it all.

- The Lord assures Joshua of his presence with him: “I will not leave you or forsake you” (v. 5); “the Lord your God is with you wherever you go” (v. 9).

- Like the disciples in Jesus’s Great Commission, Joshua is told to obey everything that the Lord commanded him (vv. 7–9), commands that he will teach to the people (vv. 10, 13).

The Great Commission initiates a new sort of conquest, as the apostles are given the church’s marching orders. No longer simply entering a promised land, they go out into a promised world.

A commission as old as creation itself

Behind all these commissions lies a more fundamental one, which we find in the first chapter of Holy Scripture:

Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it, and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over every living thing that moves on the earth. (Gen 1:28; cf. Ps 8:4–6)

Man is created and empowered to go into all the world and bring it under righteous rule.

All subsequent commissions develop out of, or return us to, this first one. The Great Commission of Matthew fulfills it: As the reign of Christ is established throughout the world, the calling of humanity arrives at its true end. In the ascension and universal lordship of Christ, humanity is exalted to its destined station (Heb 2:5–10), and, as this lordship is proclaimed throughout the world by the church, Christ’s glory is displayed.

Rejecting the satanic alternative

Alongside the fundamental human commission, a satanic alternative arises. It is seen in the serpent’s deceptive promise that godlike authority is to be enjoyed through taking the forbidden fruit. In this same vein, the summons of Babel (Gen 11:4) inverts God’s original commission: Instead of filling the earth (“lest we be dispersed”), they join their forces to build Babel. Rather than humbly obey, they rebelliously pursue self-exaltation (“let us make a name for ourselves”).

So, likewise, those hearing the Great Commission in the wider context of Matthew might also hear in Jesus’s words a recollection of the final wilderness temptation of Matthew 4:8–10:

Again, the devil took him to a very high mountain and showed him all the kingdoms of the world and their glory. And he said to him, “All these I will give you, if you will fall down and worship me.” Then Jesus said to him, “Be gone, Satan! For it is written, ‘You shall worship the Lord your God and him only shall you serve.’”

At the end of Matthew 28, we are once again on a mountain (v. 16). However, Jesus is now being worshiped (v. 17) and possesses the dominion the devil offered him at the beginning of his ministry. Having resisted the satanic temptation of Eden and Babel, Jesus is raised to the right hand of the Father as the faithful Son, realizing humanity’s proper destiny.

Conclusion

Almost two thousand years after it was given, the Great Commission continues to direct the labor of the church. Attuning our ears more fully to its rich scriptural resonance, the true greatness of what it places before us gives clearer shape and impetus to our calling.

In the Great Commission, we see the fulfillment of the promise made to Abraham in his call, of Daniel’s vision and the psalmists’ praises, the declaration of a new empire, and the outworking of a new conquest—divine grace stripping this world’s ruler of his former dominion. As Jesus’s disciples boldly proclaim his authority amidst all the rulers and peoples of this world, forming communities obedient to his word, God’s purposes for and promises to humanity will be fulfilled.

Suggested resources on the Great Commission

The Great Story and the Great Commission: Participating in the Biblical Drama of Mission (Acadia Studies in Bible and Theology)

Save $8.40 (35%)

Price: $15.59

-->Regular price: $23.99

40 Questions about The Great Commission (40 Questions Series)

Save $1.25 (5%)

Price: $23.74

-->Regular price: $24.99

Four Views on the Church’s Mission (Counterpoints)

Save $0.85 (5%)

Price: $16.14

-->Regular price: $16.99

What Is the Mission of the Church? Making Sense of Social Justice, Shalom, and the Great Commission

Save $5.25 (35%)

Price: $9.74

-->Regular price: $14.99

Great Commission, Great Compassion: Following Jesus and Loving the World

Save $0.60 (5%)

Price: $11.39

-->Regular price: $11.99

Understanding the Great Commission

Save $2.80 (35%)

Price: $5.19

-->Regular price: $7.99

The Temple and the Church’s Mission: A Biblical Theology of the Dwelling Place of God (New Studies in Biblical Theology, vol. 17 | NSBT)

Save $1.00 (5%)

Price: $18.99

-->Regular price: $19.99

The Mission of God’s People: A Biblical Theology of the Church’s Mission (Biblical Theology for Life)

Save $1.65 (5%)

Price: $31.34

-->Regular price: $32.99

Related articles

- What Is the Great Commission—& Is It Even for Me?

- What Is the Creation Mandate—and Does It Still Matter?

- What’s the Purpose of Work? How Vocations Participate in God’s Mission

- What Does It Mean to Take God’s Name in Vain? | Carmen Joy Imes on Exodus 20:7

2 weeks ago

32

2 weeks ago

32

English (US) ·

English (US) ·