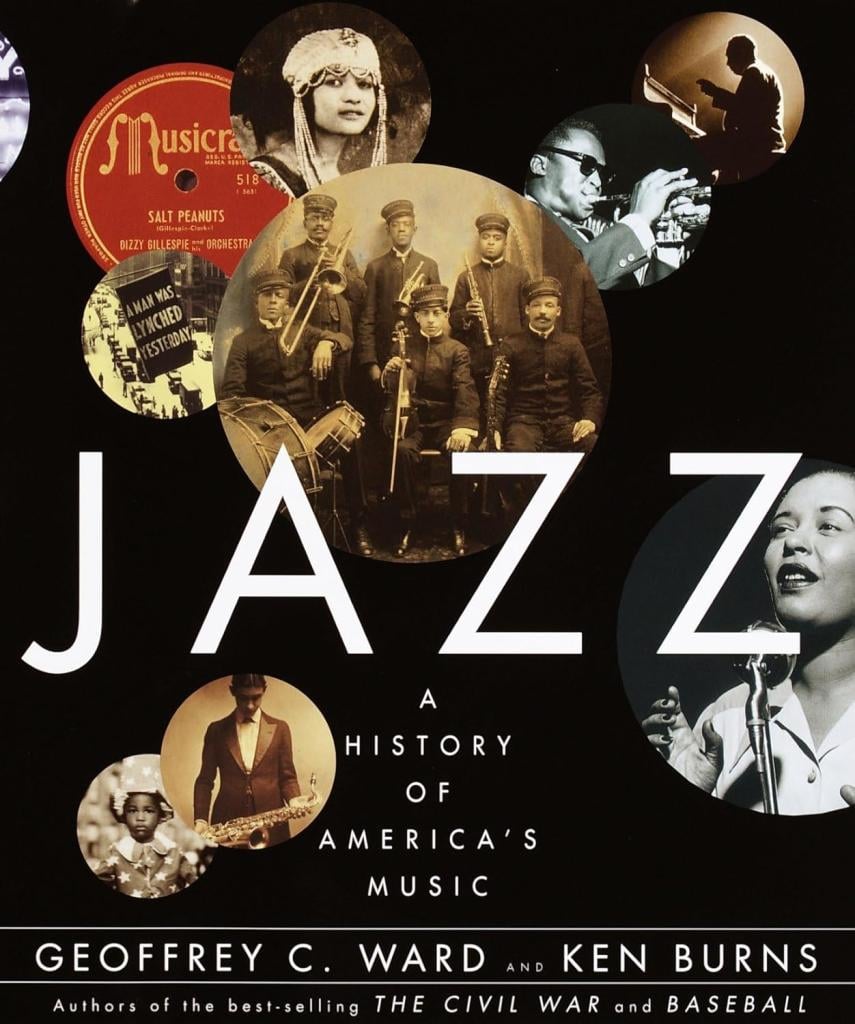

There are several excellent compendiums that survey the history of jazz in one way or another. The latest of these three major contributions is Ted Gioia’s The History of Jazz (OUP, 2021). Before that is Keith Shadwick’s, The Encyclopedia of Jazz and Blues (New Burlington Books, 2001), and before that G.C. Ward and Ken Burns’ Jazz, A History of American Music, Knopf, 2000). The latter of course accompanied Burn’s series on PBS, which was excellent as usual (though on the whole his series on the Civil War was better and award winning).

Sadly, only about 5% or less of the sales of CDs, or before that lps, are from jazz. It is indeed the most indigenous form of modern music that actually originated in the U.S., and yet the least well known. Classical music originated in Europe, as did folk music, and we could debate about rock n’ roll, because it was the British Invasion with the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and others that really led to the vast appeal and sales of rock n’ roll in America. Yes of course there was Elvis, but notice that he was channeling the blues, when he wasn’t doing show tunes and ballads of various sorts, and the blues, of Bo Diddley, Robert Johnson, Chuck Berry, B.B. King and others was ‘black’ music in its origins. So the claim by Burns and others that jazz is indeed the form of music that deserves the claim to be American born and bred is correct. And yet, it has been the most neglected art form amongst the various kinds of music. I say all this to make clear that jazz deserves all the recent detailed attention it has gotten, both on screen (Bird, Mo Better Blues, La La Land, Chicago, Greenbook, Miles Ahead…. and more from before 1988 when Clint Eastwood did Bird).

Of these three major compendiums, the visually most interesting, with the most pictures is Burns’ book, and he gives full attention to ‘white jazz’ of the big band era, Tommy Dorsey, Glenn Miller, and also to the giants of that form of jazz like Duke Ellington or Count Basie, but his book is clear that jazz and blues arose out of the black experience in the South– for instance, New Orleans, Memphis, and also the Midwest in Kansas City. What happened in the late thirties and forties and fifties was the migration of African Americans to the big cities in the north– Philadelphia, New York, Chicago especially due to all the racism and attacks on blacks, which only intensified during the Civil Rights Movement beginning in the late 50s throughout the 60s. My own home state of N.C. can attest to this migration part of the story because John Coltrane (born in Hamlet, but raised from infancy in my home town of High Point where he learned to play reed instruments), Thelonius Monk, Nina Simone, Robert Flack, and just over the border in Cheraw S.C. Dizzy Gillespie, all left and became famous in the big cities of the North. It is a sad story. I am happy to report that High Point has in more recent times honored Coltrane with a statue downtown near the performing arts center, a section in the High Point museum with his piano among other things, and the city now owns his childhood home built by his grandfather on Underhill St. near where Coltrane went to William Penn High School and learned music, and graduated. I lobbied for years for all this to happen, and am thankful it finally has. Coltrane’s famous album, A Love Supreme, was the first jazz album by anyone to sell a half million records well before the next big seller— Miles Davis’s famous Kind of Blue.

While Burns is giving us a history of jazz, much more detailed is Gioia’s, fine recent volume, except that he skimps on the recent history of jazz, including jazz fusion, and smooth jazz (which some would say is jazz lite— less filling but tastes great). If the essence of jazz is improvisation then most of smooth jazz isn’t that. But still to be clear, at least the jazz fusion of Pat Metheny and Lyle Mays deserves much more attention than it gets in these three volumes. A bare mention of Lyle Mays on one page will not do, not least because his own solo lps and films scores deserve attention. And yes, Metheny and Mays, were masters at improv. It is the Pat Metheny group that has done the most since the late 70s to spread the fame of jazz worldwide, and draw gigantic audiences all over the world, both in Europe and Asia. And without question one of the top ten jazz albums of all time is the jazz symphony entitled The Way Up in 4 movements, which was the last Lyle Mays contributed to the group, before he passed away prematurely. He was the really beneficiary of and successor to Bill Evans, and deserves far more credit.

The interesting thing about Shadwick’s volume is he divides the volume into jazz and then the blues, giving each their proper due, but raising questions about how one can make such a distinction when jazz owes so much to, and offers up blues, in the midst of jazz. And again, the more recent history of jazz is neglected in this volume. One page given to Pat Metheny and no pages to Lyle Mays will not do.

All three of these volumes are valuable resources, and as one who has spent much of the last 30 plus years learning and learning about jazz, and collecting essential samples, I am thankful for these three compendiums. Sadly, jazz is much bigger in Europe and Japan than it is here in America. Here’s a few CDs to try out if you are wanting a starter kit. Start with Scott Joplin and his ragtime piano numbers, The Complete Piano Works of Scott Joplin by Dick Hyman. Then, pick a big band lp or two— Duke Ellington’s All the Hits and More is a good starting place, and also Benny Goodman The Essential Benny Goodman. Follow this with several CDs from the classic jazz period including of course Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue and Bitch’s Brew, Bill Evans, Sunday at the Village Vanguard, and You Must Believe in Spring, and John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman, John Coltrane Blue Train, Theolonius Monk with Coltrane at Carnegie Hall, Monk Complete Albums Collection 1957-61, Weather Report, Heavy Weather, Pat Metheny Group, Offramp, Letter from Home, The Way Up, Pat Metheny solo Secret Story, We Live Here. and with Charlie Haden, Beyond the Missouri Sky. I have left out the famous vocalists of the whole period, which deserve separate attention. This is enough to get your motor running. In some ways, Shadwick’s encyclopedia is the easiest entrance into the story of jazz and blues, and there are no pictures in the third edition of Gioia’s volume, but it reads well. The Burns volume is meant to be a companion to the TV series, and so both should be explored together for a more complete picture.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·