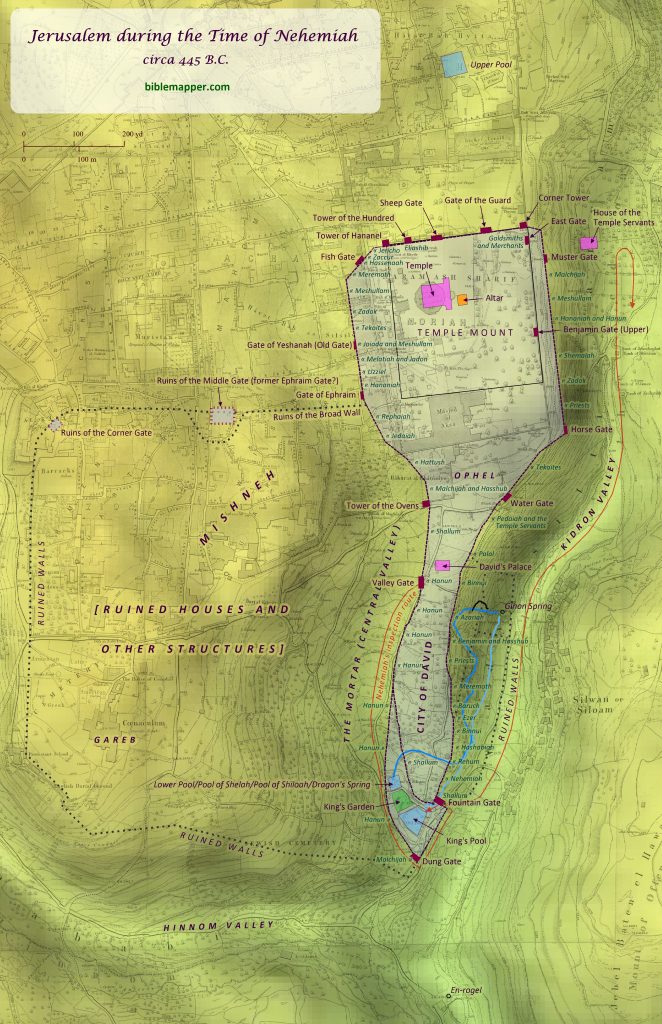

Author’s Note: This map draws heavily upon the careful work of Dr. Leen Ritmeyer (www.ritmeyer.com) regarding the probable location of gates, walls, and other features, though I have deviated at points from his data, based on my own research and conclusions.

A wealth of archaeological evidence supports the existence and location of many of the structures shown on this map, and great care has been taken to correlate them as faithfully as possible with the data provided in the book of Nehemiah and other biblical texts. Nevertheless, the specific identification of virtually all of these items is open to great debate. For this reason, no attempt has been made on this map to indicate any degree of uncertainty for the identifications that have been included, since the vast majority of these would be marked as uncertain anyway.

The shaded relief has been overlaid with the Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem (1865), by Charles Wilson.

The book of Nehemiah is one of the last books of the Old Testament written, and it recounts the efforts of Nehemiah to rebuild the walls of Jerusalem long after they had been destroyed by the Babylonians (2 Kings 24-25; 2 Chronicles 36:17-21; Jeremiah 39:1-10; see “Nebuchadnezzar’s Final Campaign against Judah” map). Nehemiah had been a trusted official in the Persian royal court who acquired a special commission to return to his ancestral land of Judea for the rebuilding effort (Nehemiah 1-2; see “Jews Return from Exile” map). After arriving in Jerusalem, he quickly surveyed the condition of the walls and then organized the people of Judea into work teams (Nehemiah 2-3). These teams each worked on a designated portion of the walls, and the entire project was completed in 52 days (Nehemiah 6:15). The builders came from Jerusalem and from towns throughout the greater province of Judea, and most of these towns are included in the map of “Judea under Persian Rule”.

It is far beyond the scope of this article to present all the textual and archaeological evidence that forms that basis for the indentifications made on this map, but two specific portions of this map seem to warrant explanation:

Ephraim Gate vs. Gate of Ephraim

The Gate of Ephraim is mentioned in Nehemiah 8:16 and 12:39, and it is noted as lying along the path of the walls that Nehemiah rebuilt. This has indirectly led to some confusion, however, regarding the location of a gate called the Ephraim Gate in 2 Kings 14:13 and 2 Chronicles 25:23, which both note that King Jehoash of Israel broke down the wall of Jerusalem from the Ephraim Gate to the Corner Gate, a distance of 400 cubits. This confusion stems from equating the Gate of Ephraim with the Ephraim Gate. Assuming the biblical text to be reliable, this assumption would require that the Corner Gate, which is mentioned also in 2 Chronicles 26:9; Jeremiah 31:38; and Zechariah 14:10, would have been located somewhere along the wall about 600 yards (549 meters) from the Gate of Ephraim. Placing it directly west of the Gate of Ephraim of Nehemiah would place it very close to the Middle Gate, perhaps suggesting that the Middle Gate was in fact the Corner Gate. But Jeremiah’s mention of both the Middle Gate (39:3) and the Corner Gate (Jeremiah 31:38) in the same book make this equation unlikely. Placing the Corner Gate directly north of the Gate of Ephraim near the northwestern corner of the Temple Mount seems plausible at first glance, but this location is very hard to reconcile with both Jeremiah 31:38 and Zechariah 14:10. Jeremiah 31:38 traces a line from the Tower of Hananel to the Corner Gate, but this would make little sense if the Corner Gate were located in very close proximity to the Tower of Hananel. Similarly, Zechariah 14:10 appears to be using the Corner Gate as a marker for the far western extreme of Jerusalem, but a location at the northwest corner of the Temple Mount hardly seems like the intended location.

A more likely solution can be found by regarding the Ephraim Gate of 2 Kings 14 and 2 Chronicles 25 as different than the Gate of Ephraim of Nehemiah, though perhaps the Gate of Ephraim had been renamed after the exile to hearken back to the old Ephraim Gate, which had been destroyed. If this is true, the Ephraim Gate may actually have been the same as the Middle Gate of Jeremiah 39:3 (Jeremiah never mentions the Ephraim Gate), or perhaps it was a gate near where the Middle Gate was built later. This location, then, would place the Corner Gate at the far western corner of the larger wall around greater Jerusalem, as shown on this map. The distance between these two gates is about 600 yards (549 meters), and the appropriately named Corner Gate would be a fitting candidate to mark the far western extreme of the city.

It should also be noted that this solution, however, requires that the Ephraim Gate existed prior to Hezekiah’s building activity. This stands in contrast to the common assertion that the wall encompassing greater Jerusalem (which Josephus calls the First Wall) was built by Hezekiah in response to the dramatic increase in residents that relocated to Jerusalem due to the fall of the northern kingdom of Israel. But the only mention in the Bible of Hezekiah building a new wall is 2 Chronicles 32:5, which notes that he built a wall “outside” the wall that was broken down (2 Chronicles 32:5). This is most likely referencing a wall in the Kidron Valley that has since been found by archaeology, and perhaps a second wall around the Temple Mount. So it would seem that elsewhere Hezekiah merely repaired or replaced portions of a wall that already existed but was in disrepair. This synchronizes well with Isaiah 22:11, where Isaiah rebukes a leader (perhaps Hezekiah) for breaking down houses “to fortify the wall” (not build a new one).

Wall Enclosing the King’s Pool

Another common assumption that is difficult to correlate with Nehemiah is the placement of the King’s Pool and the Lower Pool outside the main wall of the City of David. (The King’s Pool was like the same as the Old Pool mentioned in Isaiah 22:11. The Lower Pool appears to be alternately called elsewhere the [Pool of] Shiloah/Siloam [Isaiah 8:6] and the Pool of Shelah [Nehemiah 3:15], which is fed by the Dragon’s Spring [Nehemiah 2:13].) Two different passages in Nehemiah (Nehemiah 3:13; 12:31) clearly trace a path along a wall from the Valley Gate (likely midway up the western wall of the City of David) directly to the Dung Gate, with no mention of any other gates or distinct changes in direction. Likewise, both Nehemiah 3:15 and 12:37 note that the Fountain Gate (likely located immediately northeast of the King’s Pool on this map) was reached after passing by the Dung Gate. This author has become convinced that this requires that the Dung Gate lay along a portion of the wall that must have extended directly from the area of the Valley Gate. Further details are given in Nehemiah 3:13, which notes that Hanun and the inhabitants of Zanoah repaired 1000 cubits (1500 feet; 1372 meters) of the wall from the Valley Gate to the Dung Gate. If the Valley Gate and the Dung Gate were indeed located at the two places shown on this map, and a wall between them followed the path shown here, the distance between them along the wall would have measured about 1548 feet (472 meters), or 1032 cubits–extremely close to the 1000-cubit distance given in Nehemiah 3:13. The existence of this wall is also supported by Isaiah 22:11-12, which notes that a reservoir for the waters of the Old Pool (likely the same as the King’s Pool on this map) had been build “between the two walls.” This could be understood to refer to Josephus’s First Wall and the wall immediately north of the King’s Pool, but this author suspects instead that it is referring to the wall that must have already existed immediately south of the Lower Pool and the King’s Pool on this map.

This map is designed to be printed at 11in. x 17 in., but it may scale acceptably at larger or smaller sizes as well.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·