I’m not the least bit artistic. I can write. I can express ideas with a pen, but not images with a paintbrush.

So too, for the longest time I resigned myself to this limitation homiletically. My preaching had carefully chosen words of explanation or exposition, but lacked thoughtfully expressed pictures.

I was in this rut until, in a class with Bryan Chapell, he asked, “What do you think is the last thing your people remember about your sermon?”

I answered, “The main idea.”

“No,” he replied. “They’ll remember your last illustration. What about the second thing they’ll remember?”

“The conclusion,” someone else said.

“No,” he replied. “They’ll remember your second-to-last illustration.”

It struck me then that I was not only being homiletically imbalanced but pastorally irresponsible. My people do need my pen-work, my careful explanation. But they also need me to “paint,” to illustrate.

In this article, I hope to demonstrate how preachers can, and ought to be, “painters,” thereby adding clarity to our communication and dimension to our gospel declaration. I’ll do so by addressing the following four considerations:

Table of contents

- Should we illustrate? The precedent for illustrating

- Why illustrate? The purpose of illustrating

- How to illustrate? The practice of illustrating

- Where to get illustrations? Resources for illustrating

Conclusion

1. Should we illustrate? The precedent for illustrating

Before we consider the work of illustrating, allow us first to make a case for it by reviewing its pedigree, so we can learn from those who came before us. What we’ll find is that both the New Testament’s as well as church history’s greatest preachers prioritized illustration. If they “painted,” so should we.

Let’s consider two examples from the New Testament and another two from church history.

i. Jesus illustrated

No one illustrated more effectively and frequently than Jesus. He made constant use of illustrations.

For instance, he bookends his Sermon on the Mount (Matt 5–7) with illustrations. After the Beatitudes, his sermon’s “introduction,” he illustrates his disciples’ role as “salt and light” (Matt 5:13–16). Then he concludes the sermon with three illustrations inviting his hearers to kingdom living:

- Two gates or ways (Matt 7:13–14)

- Two trees or fruits (Matt 7:15–23)

- Two builders or foundations (Matt 7:24–27; Luke 6:47–49)1

Elsewhere, Jesus’s use of parables demonstrates his commitment to illustration. In parables, meaning is conveyed through imagery. This was his primary mode of preaching: He saturated his message with imagery intended to clarify and convey it.

Because Jesus’s message made demands on people’s lives, illustrations from life proved most sensible. A message for everyday life is best illustrated from everyday life. Thus, he drew illustration from:

- Agriculture (Matt 7:15–20; John 15:1–8)

- Farming (Matt 11:29; 13:3–9; John 10:11–29)

- Everyday objects (Matt 17:20; John 6:35; John 10:9–16)

- Significant life events (Matt 22:1–4; Luke 15:1–32; John 16:21)

Alan Cole explains the advantages of Jesus’s use of illustrations:

Jesus used many parables, vivid illustrations of spiritual truth, drawn from everyday life. Those who preach the gospel in the open air, specially in the Third World, will know well the value of this method. It captures and holds the interest of ordinary listeners, and if they are thoughtful, will lead them to see the spiritual truth. Otherwise, they will just enjoy the story, laugh and forget it, as often happened in Jesus’ day.2

Jesus’s model challenges those who prioritize explanation at the expense of illustration.

ii. The apostles illustrated

Apostolic preaching is ripe with illustrations.

- Peter illustrates the inestimable value of the gospel by contrasting it with treasure (Acts 3:6).

- Paul communicates God’s providence and abundant provision with examples from nature (Acts 14:17).

- Paul establishes a connection with his audience with a cultural reference to the poet Aratus (Acts 17:28).

As Dennis Johnson argues, the apostles’ preaching models for us an effective pattern of illustrating:

Apostolic preaching refuses to veil its world-changing truth behind dialects intelligible only to the initiated (2 Cor. 4:2–6) or to lock its life-giving power away from spiritual aliens who most need it. This missiological dimension of apostolic preaching has enormous implications for our choice of vocabulary and illustration and for our engagement with the cultures and worldviews that have molded our hearers, as we preach in the same redemptive-historical epoch as the apostles, despite the passing of two millennia.3

iii. John Chrysostom illustrated

Having considered the New Testament’s use of sermon illustrations, we now turn to Christian preaching across church history. There are several figures we could consider,4 so we’ll restrict ourselves to two of the most notable homiliticians, who in turn represent two major eras: John Chrysostom in the patristic era, and Martin Luther in the Reformation era.

Chrysostom, a nickname meaning “Golden-Mouth,” is arguably the greatest preacher of the patristic era. Philip Schaff, who edited and compiled Chrysostom’s wealth of homilies, described him as “the prince of commentators among the Fathers.”5

His greatness was in large part due to his effective use of word-picture illustrations. The beauty and warmth of his language enhanced the clarity and depth of his exposition. For example, in the conclusion of his homily on Matthew 1:1, Chrysostom says,

Thus “learn,” saith He, “of me, for I am meek and lowly in heart, and ye shall find rest unto your souls.” Therefore in order that we may enjoy rest both here and hereafter, let us with great diligence implant in our souls the mother of all things that are good, I mean humility. For thus we shall be enabled both to pass over the sea of this life without waves, and to end our voyage in that calm harbor; by the grace and love towards man of our Lord Jesus Christ, to whom be glory and might for ever and ever. Amen.6

Here he employs two metaphors, a mother and a peaceful voyage into a harbor, to explain the value of humility. What makes his use of illustrations so strong is not primarily their verbal beauty but how they aid clarity.

Chrysostom also relied heavily on the Bible for illustrations. M. B. Riddle explains, “The same study [of the Bible] gave him the wealth of Scriptural illustration and suggestion so noticeable in his Homilies. Knowledge of the whole Bible and love of the whole Bible are manifest everywhere.”7

Yet whether the Bible’s or his own, illustrations mattered greatly to this chief patristic expositor. If one with a “Golden-Mouth” prioritized illustrations, how much should we of more ordinary skill strive after the same?

iv. Martin Luther illustrated

Martin Luther is unquestionably a leading expositor of the Reformation era, immensely skilled at illustrating. But he wasn’t only good at illustration, he also made frequent use of it. R. C. Sproul explains the importance of illustrations for Luther: “That which makes the deepest and most lasting impression on people is the concrete illustration. For Luther, the three most important principles of public communication were illustrate, illustrate, and illustrate.”8

Like Chrysostom before him, Luther prioritized both word-pictures and biblical illustrations. For instance, in a sermon on John 1, Luther provides the following illustration, explaining the relationship of the New to the Old Testament:

The New Testament is not more than a revelation of the Old, just as when a man had first a closed letter and afterwards broke it open. So the Old Testament is a testament epistle of Christ, which after His death He opened and caused to be read through the Gospel and proclaimed everywhere.9

Whether or not you agree with Luther’s hermeneutic here, he displays the strength of a powerful word-picture. It is brief, specific, and clarifies the key idea. The listener’s mind both works and rests: It works because the image functions as explanation, yet it rests because the image helps the mind “see” rather than give it more information to process.

Luther also used biblical narratives for illustration. Sproul explains, “He encouraged preachers to use concrete images and narratives. He advised that, when preaching on abstract doctrine, the pastor find a narrative in Scripture that communicates that truth so as to communicate the abstract through the concrete.”10 Luther historian Roland Bainton observes that the key to Luther’s powerful use of illustrations was his strong imagination. He “loved to think how he would have felt if he had been there—Mary, Joseph, the Shepherds and the wise men.”11

We may not be blessed with Luther’s imagination or verbal skill. But if we cannot match him in practice, we should certainly replicate how he prioritized illustrating.

v. We should illustrate

As we’ve seen, the New Testament assumes the use of illustrations in preaching: Both Jesus and the apostles illustrated in order to aid their teachings. An absence of illustrations would have been foreign to New Testament preaching. And beyond the New Testament, the church’s greatest preachers were likewise masterful illustrators.

Homiletical history is unanimous: Illustrations matter. Despite variations in their approaches, all major Christian preachers have used illustrations to clarify and enrich their sermons since the beginning.

Most of us would acknowledge the value of illustrating. In practice, however, it can be easy to give illustrations the least of our homiletical efforts. Perhaps you’ve had the experience. You get to the end of your week of sermon prep, and then it hits you: You didn’t plan for any illustrations! This is not merely poor homiletical planning. It’s a lack of homiletical priority.

If we would follow the greatest preachers—those of Scripture and history—we must prioritize illustrations. We cannot, whether intentionally or by negligence, relegate them to the margins of our preparation. To deprioritize illustrations is to reject the witness of our greatest homiletical heritage.

Write your sermons using Sermon Builder with a free trial of Logos today!

2. Why illustrate? The purpose of illustrating

Having made a case for illustrations, let’s consider their purpose. What is the point of “painting”?

As I’ll explain, illustrations serve two purposes:

- To provide clarity in communication

- To regulate the listeners’ life with the gospel

Preachers should illustrate for homiletical clarity and gospel practicality.

i. For clear communication

Clarity is the prime pursuit of homiletical strategy (Col 4:4), and illustrations are fundamentally instruments of clarity. To illustrate means to “throw light” on a subject.12 Jay Adams calls them aids to comprehension.13 They are not primarily intended to engage, though they may. They are primarily intended to enhance meaning.

When we plan illustrations, we should not consider where people may be bored, but where they may be confused.

We are more likely to misuse illustrations when we consider them a function of creativity over clarity. We must not think about illustrations primarily as decorations to spruce up a wilted sermon. When we plan to deploy an illustration, we should not consider where people may be bored, but where they may be confused.

ii. For gospel regulation

Illustrations can bring the gospel into the normal elements of life. Well-crafted word pictures associate divine meaning with the ordinary. We set narrative illustrations within the grand metanarrative. We use historical illustrations to proclaim the victories of the gospel throughout time. We share biblical illustrations that culminate in the gospel. I’ve found no better summary of this principle than James Kay’s:

If the turn of the ages has taken place in the cross and continues to take place in the work of the cross, then what is required of preachers are not simply illustrations from history and nature, but illustrations that place history and nature, indeed all of life, into the crisis of the cross.14

Illustrations are not merely homiletical devices but theological resources. Grant Osborne explains:

The whole world surrounding you is a treasure house of metaphors, examples and illustrations. The purpose of an illustration is to awaken the senses of the audience so they can feel the point of the text in a fresh, evocative way. You are building a word picture in their minds, turning their senses into a rich canvas onto which you are painting a portrait of the biblical truth involved.15

In fact, Osborne contends that illustrations are a subset of application,16 as illustrations from everyday life serve to bring our lives under the subjection of the Scriptures and the gospel.

Thus, we illustrate as part of stewarding the gospel. Our congregations do not need more creativity, entertainment, or engaging delivery tactics. They need illustrations that view their lives through the lens of the gospel. Be a painter, for the gospel’s sake.

3. How to illustrate? The practice of illustrating

But now that we’re committed to illustrating and understand it’s purpose, how should we illustrate? Allow me to provide some practical suggestions on how to use your paintbrush effectively—as well as some sloppy brushstrokes to avoid.

i. Types of illustrations to use

a. The Bible

The Good Book is your richest mine for illustrations. Use Bible stories and characters to reinforce a truth or idea.

An important caveat: When using Scripture to illustrate, distinguish it by varying your language and delivery so that it doesn’t come across as additional explanation. One benefit of an illustration lies partly in allowing the mind a moment of rest, a shift in how information is processed. So use illustrative language. Don’t just compound biblical content.

b. Stories

Stories can be either fiction or non-fiction, from your own life, history, or elsewhere. Good illustrations can come from anywhere.

But remember, let the meaning you intend to illustrate drive the story. Don’t let the story drive. If you tell a story, tell it well—but never at the expense of your sermon.

c. Word-pictures

These are a favored type of illustration. They provide clarity, yet are very time-efficient. They allow you to say a lot with a few words. Again, refer to our aforementioned homiletical heavyweights.

d. Church history

Illustrations drawn from church history—whether events, stories, or people—inspire, engage, and naturally integrate into sermons.

Additionally, illustrations from church history can help anchor congregations in who they are and where they come from. Sermons offer wonderful opportunities to reorient congregations to their theological heritage.17

ii. What to avoid when illustrating

a. Preaching the illustration itself

We’ve all done this or heard it done. We walk away remembering the illustration—but not it’s point. Don’t let your delivery of an illustration overtake or cloud its homiletical intent. An illustration must serve the sermon, not overshadow it.

b. Wasting time

You only have so much time, and illustrations supplement the text. So don’t let them take over.

I don’t manuscript, but I generally write my illustrations so that I don’t waste time searching for clarity as I deliver them.

c. Making yourself the hero

If using yourself as an example, don’t crown yourself the hero. We are broken mouthpieces and bumbling heralds for the king of glory. Let’s say what God has said and sit down.

d. Complicated illustrations

Simpler is better. If you have to construct an illustration before you can use it, it’s too complicated. Illustrations exist to explain and clarify. They should not require explanations themselves.

Discard a forced illustration rather than muddy your canvas with confused explanation.

4. Where to get illustrations? Resources for illustrating

To conclude, allow me to offer some suggestions on where to get your “painting supplies.”

i. Live curiously

Develop the “homiletical habit,” observing everything through a preaching lens.18 For example, our aforementioned Chrysostom mastered this habit:

He watched the ships and the sailors, acquainted himself with the customs, good and bad, of commercial life, curiously inspected a great variety of mechanical processes, often visited his farm and closely observed agricultural operations and the various phases of rural life, was constantly seeing and hearing what occurred in his home and in other homes that he visited, supplemented his own observation by inquiring of others as to all the manifold good and evil of the great world that surged around him, and everywhere and always was asking himself, till that became the fixed habit of his mind, What is this like? What will this illustrate?19

Ask homiletically curious questions about everything:

- “What does [blank] teach me about God?”

- “What elements of theology might be represented in [blank]?”

- “How is God teaching me about his love in [nature, my parenting, etc.]?”

Logos’s Sermon Assistant can generate illustration ideas based on your sermon. Try Logos for free!

ii. Read widely

Read books on various topics and times. Illustrations will jump off the page to those refining their “homiletical habit.”

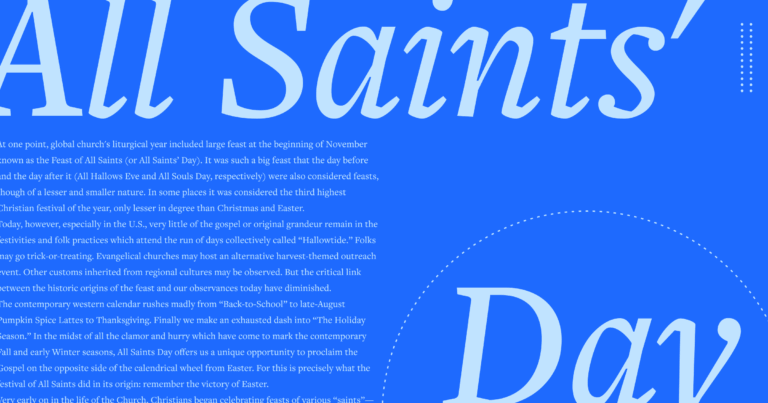

iii. Use Logos

Logos makes finding illustrations in your digital library easy. Use the Illustration section in Logos’s Guides to locate illustrations on any given passage.

For instance, I’m currently preparing a sermon on Nehemiah 9–10. When I entered this reference in my Passage Guide, the Illustrations section provided a word bubble of topics related to my passage (see image below). Click on a topic, and Logos will provide a list of illustrations to open and explore.

Conclusion

Preacher and teacher, your congregation needs to hear the Word clearly and the gospel beautifully. So use your pen, but also improve your skill with a paintbrush.

Kyle Grant’s recommended books on sermon illustrations

On Preaching: Personal & Pastoral Insights for the Preparation & Practice of Preaching

Save $0.55 (5%)

Price: $10.44

-->Regular price: $10.99

Illustrating Well: Preaching Sermons that Connect

Save $4.90 (35%)

Price: $9.09

-->Regular price: $13.99

Using Illustrations to Preach with Power

Save $3.85 (35%)

Price: $7.14

-->Regular price: $10.99

Preaching the Word with John Chrysostom

Save $0.60 (5%)

Price: $11.39

-->Regular price: $11.99

Preaching Illustrations from Church History

Save $0.75 (5%)

Price: $14.24

-->Regular price: $14.99

The Modern Preacher and the Ancient Text: Interpreting and Preaching Biblical Literature

Save $1.95 (5%)

Price: $37.04

-->Regular price: $38.99

A Manual for Preaching: The Journey from Text to Sermon

Save $9.00 (30%)

Price: $20.99

-->Regular price: $29.99

Related content

- How to Prepare a Sermon: 32 Hacks for Preachers

- 4 Steps to Faster Sermon Prep (Without Sacrificing Quality)

- Top Preaching Tools & Resources That Belong in a Pastor’s Library

- Pastor, Learn How to Maximize Your Sermon Prep

- Sermon Planning: How to Get Ahead without Stressing Out

4 weeks ago

37

4 weeks ago

37

English (US) ·

English (US) ·