Even while professional theologians celebrate the 1700th anniversary of the Council of Nicea (325 C.E.), its formulations of classical Christology remain largely unknown and strange among lay folks. To many the christological affirmations of the Nicene[-Constantinopolitan] Creed from 381 sound curious at their best and alien at their worst:

- “begotten of the Father before all ages,”

- “very God of very god,” or

- “of one essence with the Father”!

And add to the puzzle that this divine figure was also the incarnate, the human person, to suffer, die, and to be buried! No wonder that this “two-nature Christology” raises the question of the relevance and meaningfulness of classical creedal affirmations. Why bother with technical terms such as homoousios (of one essence)?

So, what is the legacy of the statement of Nicea (325) and the ensuing creed (381), as well as the summit of all early christological creeds, namely Chalcedon (451)? This essay suggests for your consideration this tentative answer: Classical creedal christological affirmations continue to serve as the authoritative yardstick and guide for our times as long as the creed’s nature is to be conceived as a “horizon” or a “perspective” rather than a fixed formulation. I suggest that the classic creeds are authoritative relatively speaking, in relation to their intended work. That is the way, I believe, the creeds best serve the ever-diversifying world Christianity of our times.

To develop my claim, I will focus mostly on the Chalcedonian Definition as it is the significant culmination of the long development started at Nicea. While I am not claiming a direct historical connection between Nicea and Chalcedon, there is no denying that the legacy, the continuing meaning and significance, of Nicea culminated in Chalcedon.

I develop the discussion in three stages:

- I will briefly address Christianity’s global diversity and its significance to our topic.

- I will remind us about what the Nicene and Chalcedonian creeds were—or were not—all about.

- This will help us to re-imagine creeds’ meaning through theological-hermeneutical lens as a “horizon” rather than positive definition.

The diverse, global context of the creeds

Contrary to some voices, the global nature of Christian church and theology is not a new phenomenon. In fact, the church has been global and diverse from the very beginning: linguistically, geographically, culturally, ethnically, and so forth.

The implications of this to the content and nature of the creeds are many. For instance, the Roman-Hellenistic vocabulary and way of argumentation at Chalcedon did not do justice to the Church in the East beyond the Greek-speaking church (the main actor in the drafting of the creeds). Particularly painful was its reception in the Syriac-speaking Christianity and its spread in China and many other places. They, of course, came to be accused of the Nestorian heresy. On the other side, the Chalcedonian miaphysite controversy led to African and Asian Christian communities being labeled heretical, creating a division with the West that continues to this day. Just think of the beginnings of Christianity in India!

In sum, the patristic church that first established the creeds along with the contemporary church which continues to embraces them are both global and diverse. This has everything to do with the ways the creedal statements are to be understood and appropriated.

What the creeds were—or were not—all about

The Council of Chalcedon (451) represented only the leaders from the Greek speaking and Latin speaking segments of the church. It attempted to solve the christological debates in a way that could be embraced by both Alexandrians and Antiochenes, the main segments in the Christian East, and the Christian West (whose influence was on the rise particularly due to the growing influence of Rome). As the late historian of theology Jaroslav Pelikan aptly stated: Chalcedon was “an agreement to disagree.”

Even then, the church fathers—and they were all men as far as we know—were not the only stakeholders in the issues of then world Christianity. What about the Middle East, to use a somewhat elusive characterization, or the Church of the East? And some other early Christian centers?

The Council, of course, never reached its noble goal to unite Christians over the christological issues—not even among the sections of early Christianities which were participants in the process! The only thing the Council could do was to combat the major deviating views present among the Greek and Latin communities.

Reaffirming the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, Chalcedon rejected what has become to known as Nestorianism and forms of miaphysitism (Apollinarism and Eutychianism). It sufficed to try to steer a middle course between the dangers of Nestorianism, which separated the two natures—thus its use of the words “indivisibly” and “inseparably”—and Apollinarianism (as well as, Eutychianism), which eliminated the distinction between the two natures—thus its use of the words “inconfusedly” and “unchangeably.”

On the one hand, Chalcedon functioned as a signpost pointing in the right direction, and on the other hand, it was a fence separating orthodoxy and heresy.

The council, however, was unable to state definitely how the union of the two natures occurred (and how it could be possible for a finite human mind to grasp this divine mystery). In fact, provided that Jesus Christ was both truly divine and truly human, the precise manner in which this is articulated or explored is not of fundamental importance for faith. One could perhaps say that, on the one hand, Chalcedon functioned as a signpost pointing in the right direction, and on the other hand, it was a fence separating orthodoxy and heresy.

As said, the terminology, worldview, and even the way of argumentation at Chalcedon, trying to negotiate the many misunderstandings and lack of understanding between Latin and Greek theologies, used intellectual tools quite foreign to, say, the Syriac church and many miaphysite churches. Hence, not surprisingly, our current world Christianity with its ever intensifying diversity and plurality often struggles as to how to best understand and appropriate the creedal statements stemming from Nicea.

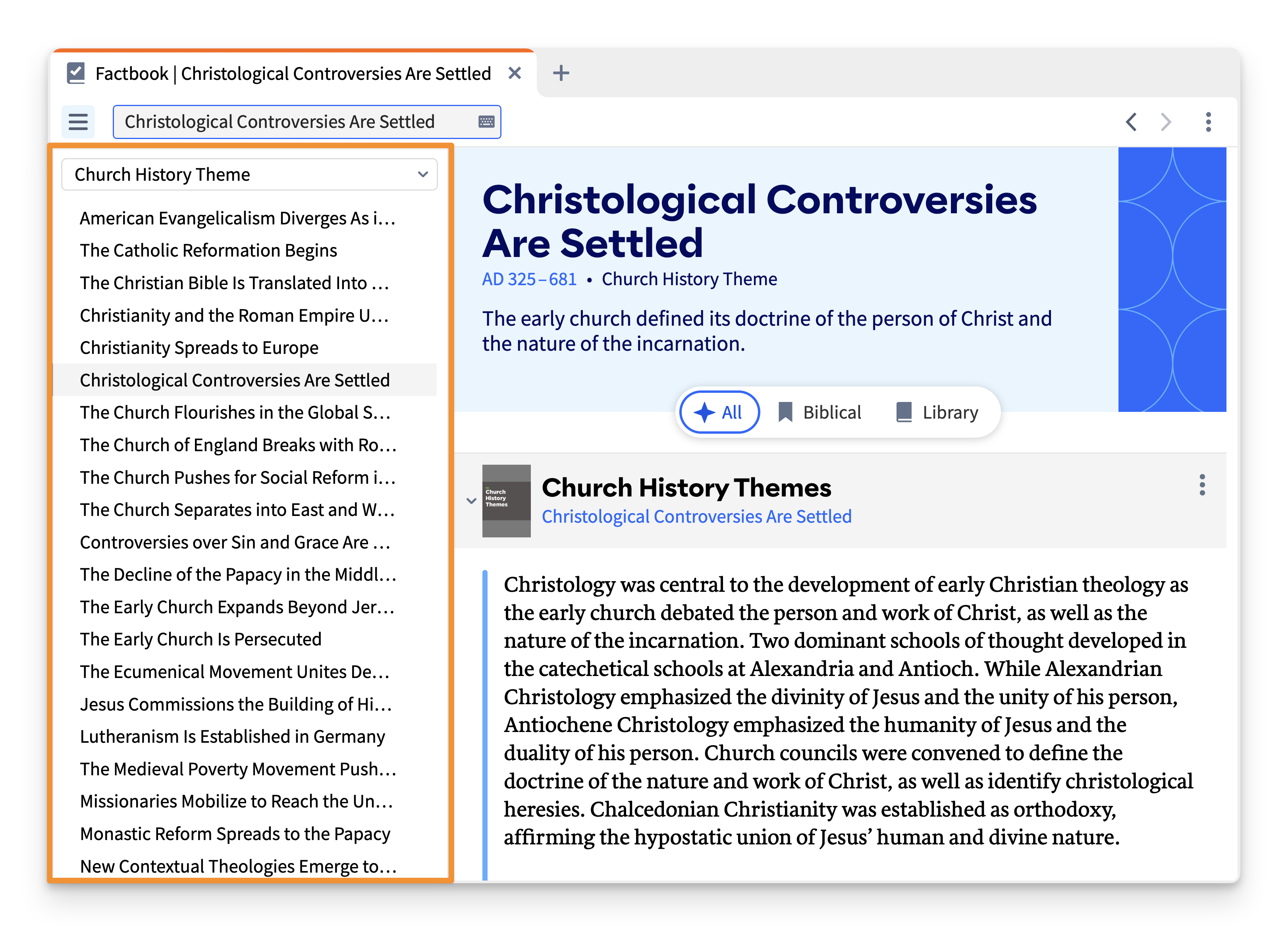

Make use of Logos’s Church History dataset to jumpstart your study on topics like early church Christology.

A way forward: Chalcedon as a “horizon”

Insightfully, Sarah Coakley prefers to speak of Chalcedon (and in my interpretation, of other creeds as well) in terms of a horizon rather than a definition. Note that the etymology of the Greek term for “definition” is horos, from which we get horizon. The other related meanings of horos are boundary, limit, standard, pattern, and rule.

The last one particularly reminds us of the way early Christianity understood creedal statements—they were “rules of faith” (regula fidei). The term “rule” means something like guidance and boundaries that help the community of faith to rule out heretical views and point to the shared consensus, even when many things are not exactly defined. The classic term “analogy” and the current term “metaphor” reflect the same kinds of sentiments. Even the old term of “symbol” used of the creeds reminds us of the same.

This is not to say that therefore the creedal (or doctrinal) statement is not understood to refer to something that really happen. It is rather to say that the creed speaks of something believed to have really happened but in a way that can only be expressed in terms of an analogy, symbol, or rule of faith. This is what Karl Rahner was aiming at when reminding us that every theological formula, including Chalcedon, is “beginning and emergence, not conclusion and end.” Theological formulation is a “means … which opens the way to the-ever-greater-Truth.” This helps put the (Chalcedonian) creed in the right perspective:

We shall never stop trying to release ourselves from it, not so as to abandon it but to understand it, understand it with mind and heart, so that through it we might draw near to the ineffable, unapproachable, nameless God, whose will it was that we should find him in Jesus Christ and through Christ seek him. We shall never cease to return to this formula, because whenever it is necessary to say briefly what it is that we encounter in the ineffable truth which is our salvation, we shall always have recourse to the modest, sober clarity of the Chalcedonian formula. But we shall only really have recourse to it (and this is not at all the same thing as simply repeating it), if it is not only our end but also our beginning.

In the final analysis, the basic affirmation of Nicea and Chalcedon, namely, the coming together of the divine and human in an irreversible yet distinguishable unity, can be appropriately called a mystery and metaphor. It is mystery in the sense that it goes beyond human capacity to understand. It is paradox in the sense that it is a statement against our expectations. However, it is not so much against reason that it is a contradictory or senseless statement. Finally, it is metaphor, a picture of reality that goes beyond ordinary language, yet depicts events that have happened. So, it is a “true” metaphor.

As a rule of faith, the creedal christological affirmation is a “grid” through which reflections on Christ’s person and work pass.

As a rule of faith, the creedal christological affirmation is a “grid” through which reflections on Christ’s person and work pass. As such, it only says so much, and even of those things it considers important to delineate, it does not say everything. Indeed, it leaves open a host of issues, including the most obvious one: What is it that “human” and “divine” nature consist of?

Conclusion: creeds as guides to our Savior

In the midst of all questions and debates—ancient and contemporary—about the legacy of Nicea, let us keep in mind clearly the ultimate question, namely the soteriological intent: By confessing belief in the God-man, Jesus the Savior, these early Christians succinctly expressed the grammar of their salvation.

At the same time, they also wanted to say as much as they could about the person and “nature” of the Savior. Coakley summarizes Chalcedon:

It does not … intend to provide a full systematic account of Christology, and even less a complete and precise metaphysics of Christ’s makeup. Rather, it sets a “boundary” on what can, and cannot, be said, by first ruling out three aberrant interpretations of Christ (Apollinarism, Eutychianism, and extreme Nestorianism), second, providing an abstract rule of language (physis and hypostasis) for distinguishing duality and unity in Christ, and, third, presenting a “riddle” of negatives by means of which a greater (though undefined) reality may be intimated. At the same time, it recapitulates and assumes … the acts of salvation detailed in Nicea and Constantinople.

All this is to say that as authoritative pan-Christian statements, what Nicea and Chalcedon are saying provides us a horizon and a rule about Jesus of Nazareth, the Son of God, our Savior. The creeds are the church’s indispensable means to express something crucial about the divine mystery. As Dietrich Bonhoeffer put it, “The Chalcedonian Definition is an objective, but living, statement which bursts through all thought-forms.”

Recommended resources from Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen

- Sarah Coakley, “What Does Chalcedon Solve and What Does It Not? Some Reflections on the Status and Meaning of the Chalcedonian ‘Definition,’” in The Incarnation: An Interdisciplinary Symposium on the Incarnation of the Son of God, ed. Stephen T. Davis et al. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), chap. 7.

Christ and Reconciliation: A Constructive Christian Theology for the Pluralistic World, vol. 1

1 month ago

24

1 month ago

24

English (US) ·

English (US) ·