Riddles were the currency of Israel’s sages—those authors of the book of Proverbs. Because their community looked to them to solve life’s riddles, we should not be surprised to find them responding with riddles of their own.

Yet until we learn to unravel their riddles, many messages in Proverbs will remain hidden from us.

This article argues that Proverbs consists of numerous cohesive poems, challenging a longstanding practice of proof texting from Proverbs.

Table of contents

Proverbs’ 3 forms of riddles

First, let’s identify the types of riddles that occur in Proverbs.

1. Riddles within single sayings

At the most basic level, riddles often reside in the single sayings of Proverbs.

Frequently, sages explained an abstract concept by comparison with a concrete image. In fact, the Hebrew for “proverb” (מָשָׁל) means “comparison.” In one instance, they compared the onset of social strife (an abstract concept) to a tiny trickle of water starting to escape, as if from the base of an earthwork dam (the corresponding concrete image; see Prov 17:14). From this abstract/concrete comparison, the hearer should deduce that social strife must be resolved swiftly, before too much damage is done and the trickle becomes a flood.

For more examples of concrete/abstract riddles within a single saying, consider how “binding a stone into a catapult” compares with “giving glory to a stupid person” (26:8), or how “a gold ring in a pig’s snout” compares with “an attractive woman who turns away from discriminating taste” (11:22).1

2. Riddles beyond single sayings

The sages also fashioned riddles that reached beyond the level of single sayings.

At times, a pair of adjacent sayings seem to contradict each other, as with this pair from chapter 26:

Do not reply to a stupid fellow in a manner corresponding to his folly, lest you become like him—even you! (26:4)

Reply to a stupid fellow in a manner corresponding to his folly, lest he become wise in his own estimation. (26:5)

The riddle resolves when the two are read in light of each other: We see that it is folly to treat all fools alike.

3. Lengthy riddles: Proverbs’ poems

It seems reasonable to recognize riddles operating within single sayings, or even in adjacent verse pairs. Conversely, to ignore these riddles would miss the sages’ intended meaning.

But how far may such riddles run? How broad was the sage-poet’s capacity for composing more lengthy, cohesive poems or poetic lectures?

None question the sages’ capacity for composing poems. We need only recall a few examples:

- The gang’s overtures (Prov 1:10–19)

- Wisdom’s counter-overture (1:20–33)

- The witless youth (7:1–27)

- Lady Wisdom’s resume (8:1–36)

- The competition between Lady Wisdom and Dame Folly (9:1–18)

- A farming lesson (27:23–27)

- The alphabetic acrostic of the resourceful wife (31:10–31)

But what about the great remainder of riddles, the remaining portions of Proverbs 1–9, and yet still broader swaths within chapters 10–29? Could it be that poems populate these regions as well?

The broader context of a poem imparts richer meaning to each constituent proverb. When read cohesively as a poem, individual sayings join to deliver a more dynamic message.

Herein lies Proverbs’ richest riddle—to responsibly recover poems beyond those that emerge so obviously. For wherever a poem comes into view, the broader context of that poem imparts richer meaning to each constituent proverb. Further, when read cohesively as a poem, individual sayings join to deliver a more dynamic message, much as an entire orchestra is able to deliver a richer performance than that of a solo instrument.

3 steps to identifying Proverbs’ poems

The challenge lies in taking care lest we invent poems not originally present, rather than recovering a structure that is truly indigenous to the composition. We must listen to the text deeply and repeatedly until it discloses its own architecture.

Three steps are necessary if we would recover poems, rather than invent them. Those steps involve:

- Detecting outer borders

- Tracing internal coherence

- Second-guessing seeming discontinuities2

These steps must first be studied among the more obvious poems (esp. in Prov 1–9) until we “get the feel” for how the sages constructed their poetic lectures. Then we can venture into subtler, more sophisticated regions (esp. chs. 10–29). For that reason, most of the illustrations offered below derive from chapters 1–9. They show that the principles are grounded in the sages’ simpler, more obvious poems.

Use the Compare Pericopes tool in Logos’s Passage Analysis to view how versions structure Proverbs.

1. Detect a poem’s borders

“Borders” refer to beginnings and endings of poems. The sages established these textual boundaries using the following six devices:

A. Shift in theme

Sages would signal a poem’s beginning (or the start of a major portion within a poem) by a shift in theme or by inserting a wisdom commendation, or both. For an example of shift in theme, notice how a warning against the lure of the gang (Prov 1:10–19) transitions to an invitation issued by Wisdom (1:20–33). Or consider how the young man’s tragic susceptibility to the seductress (7:1–27) gives way to a majestic hymn lauding the capabilities of Lady Wisdom (8:1–36).

B. A wisdom commendation

The second marker of beginnings involves a wisdom commendation. This refers to a saying (sometimes more than one) that commends the worth of wisdom generally, without expressing situation-specific advice. Consider these examples, noting especially the high value placed on wisdom (or synonyms such as “instruction,” “commandments,” “reproof,” “insight,” or “words”), combined with the absence of situation-specific advice:

My son, my instruction you must not forget, and may your mind preserve my commandments. For longevity, years of life and peace will they add to you. (Prov 3:1–2)

Listen, my sons, to a father’s reproof, and pay attention so that you may learn insight. (4:1)

Listen, my son, and take my words so may they multiply for you years of life. (4:10)

Some wisdom commendations take the shape of imperatives (as with the three examples above; cf. Prov 4:20–22; 5:1–2; 6:20–24; 7:1–5). Other commendations elevate wisdom without issuing an imperative, as seen in the next examples. Each of these, too, marks the start of a poem.

The Proverbs of Solomon. A wise son will bring a father joy, while a stupid son is his mother’s grief. (Prov 10:1)

To engage in planning seems like a joke to a stupid person, but it is wisdom to a perceptive person. (10:23)

Whoever loves reproof loves knowledge, while one who hates reprimand is dense. (12:1)

C. Closure

In addition to signaling poem-beginnings through predictable literary devices, the sages also tended to mark the end of poems (or the close of major portions within a poem) through one or more characteristic devices. These include closure, inclusio, recap, and character summary.

Closure operates when either concepts or actual words or phrases that appeared earlier in a poem recur in concentrated fashion toward that poem’s close. Thus in the poem spanning Proverbs 1:1–9, four components appear at various points in verses 1–7, then produce closure when they reappear in concentrated fashion in the poem’s final two sayings (vv. 8–9). Those four components are “son,” “reproof,” “listen,” and “epitome”/“head” (the last two terms are etymologically linked).

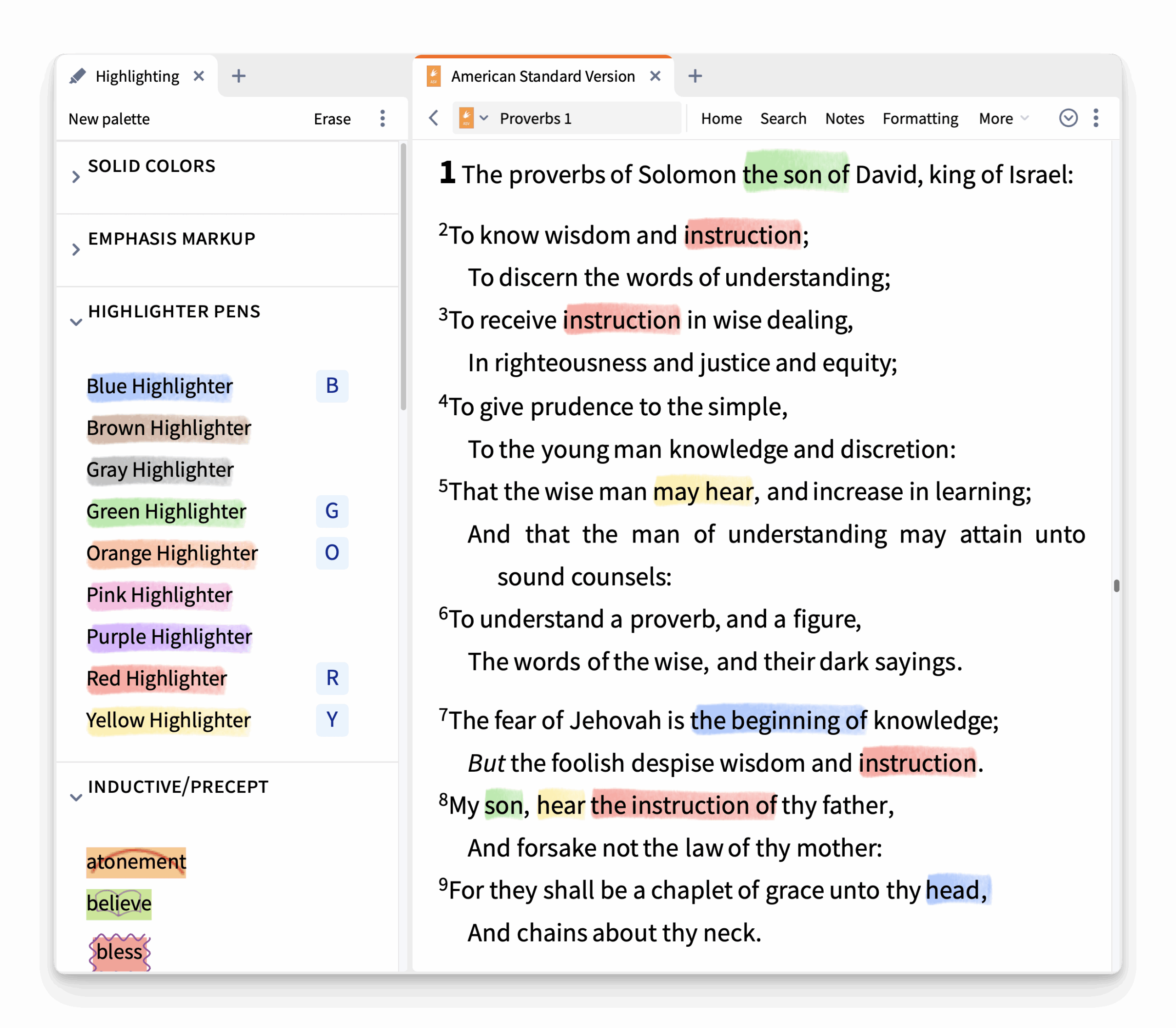

Logos’s Highlights tool used to identify repeated Hebrew words in Proverbs 1:1–9.

D. Inclusio

Inclusio, a second way to signal a lower border, also involves closure, but on a narrower scope. Here the recurring term or concept must appear at the very first saying and again in the very last saying (or close to either of those points). An inclusio operates in the poem spanning Proverbs 4:20–27, since the instruction to “turn” (נטה) appears first in verse 20 (stated positively) and again in verse 27 (as a prohibition).3 Inclusio occurs also in the poem spanning Proverbs 21:5–22:16. There the expression “surely winds up in need” appears in 21:5 and again in 22:16.

It should be noted that a form-related device such as inclusio (form-related since it operates independent of meaning) does not by itself suffice to establish the borders of a poem. It must be corroborated by additional formal devices, such as broader evidence of closure or by a content-based device such as continuity of theme. For instance, the borders marked by inclusio (a formal device) in the poem spanning 21:5–22:16 are further endorsed by both closure and theme-based continuity.4

E. Recap

Recap, a third device to mark a lower border, obtains when principal points established earlier in a poem reappear in tighter rank towards its close. (In contrast to recap, closure can operate when isolated expressions—or merely minor points—reappear later in a poem.) As an example, notice how a poem devoted to warning against adultery (Prov 6:20–35) concludes by reinforcing (a) the certainty of punishment and (b) the source which explains that ineluctable punishment (i.e., the enraged husband). Those final four sayings (vv. 32–35) form a recap, reinforcing the message lying at the core of that entire lecture (for further examples of recap, cf. 13:24–25 and 20:2–4).

F. A character summary

The character summary offered the sage a final device for marking lower boundaries. A character summary consists of one or two (occasionally more) sayings that shine the spotlight on a particular character trait, whether commending it or, if undesirable, censuring it. Often diametrically opposed characters appear side by side in a character summary, implicitly requiring the reader to choose which character he or she now will emulate. The poets of Proverbs employed character summaries rather liberally to mark the close of a poem or a major portion (e.g., 3:34–35; 21:3–4). A character summary may also appear before the close of a poem (e.g., 11:8; 14:11, 19, 34).

One such character summary closes the poem in which Wisdom extends her offer to enroll pupils (Prov 1:20–33). Here “the naïve” and “fools” comprise the negative character alternative in verse 32, while “one who listens” to wisdom epitomizes the recommended character trait in verse 33.

Surely the waywardness of the naive will slay them, and the fools’ complacency will destroy them. But one who listens to me shall dwell securely and will remain undisturbed by dreadful terror. (Prov 1:32–33)

An aside may be helpful at this point. Since the sage typically used the barest of outlines to sketch a character summary, that summary may only vaguely resemble the thrust of the poem as a whole. Consequently, the modern reader will be inclined to disregard the character summary—a rather simplistic letdown at the close of a robust and dynamically persuasive lesson. Instead, we should treat the character summary as an invitation to pause, to reflect carefully on all that the sage has been urging through a given poem. Then we must select with determination the path of the wise character.

2. Trace internal coherence

For outer borders to be reliable markers of a poem, the content found within those borders must demonstrate a reasonable degree of coherence. The sages fostered coherence within poems by various combinations of the following six devices:

A. Repetition & multiple synonyms

To illustrate such coherence fostered by repetition of identical words or phrases and by multiple synonyms, notice in the poem spanning Proverbs 4:1–9 how the expression “my words” repeats verse 4 and again in verse 5b (inclusio on a small scale, since vv. 4–5b present the first segment of the grandfather-sage’s principal teaching). Notice also how the synonyms “love her” and “cherish her” appear in verses 6 and 8–9 (another small-scale inclusio, since vv. 6–9 give the second segment of that principal teaching). By repeating the double exhortation, “Acquire wisdom! … [A]cquire insight!” in verse 5a and again in verse 7, the sage laces together the first and second principal teachings (vv. 4–5b coheres with vv. 6–9).

Use Logos’s Emphasis Visual Filter to identify repetition.

B. Imperative-plus-incentive

Imperative-plus-incentive (or explanation) comprises a third device fostering coherence within a poem. Notice how the imperative-incentive connection joins the following sayings:

- Imperative: “My son, my instruction you must not forget, and may your mind preserve my commandments” (Prov 3:1).

- Incentive: “For longevity, years of life and peace will they add to you” (3:2).

Or again in chapter 5:

- Imperative: “Keep your way a good distance from her [i.e., the strange woman], and do not approach the door of her house” (5:8).

- Incentive: “Lest you give over to outsiders your splendor, and your years to the cruel” (5:9; further incentives extend through v. 14).

C. Dual-theme introduction

A dual-theme introduction creates coherence by presenting two themes initially in a compressed manner, after which each theme is expanded in turn. Thus in the poem describing the gang’s efforts to recruit the naïve youth, the opening saying presents in compressed form both the gang’s appeal (Prov 1:10a) and the wise response of refusal (v. 10b). Thereafter, the gang’s offer unfolds in greater detail (vv. 11–14), followed by a detailed explanation of why the youth must refuse that offer (vv. 15–18). Occasionally such an introduction launches not two themes, but three (e.g., 15:7, where this initial verse of a poem introduces themes of discernment, disbursing counsel, and a healthy mind).

D. Palistrophe

A palistrophe (or extended chiasm) describes coherence that results when a series of concepts or terms reappear in reversed order (A, B, C, C’, B’, A’, or alternatively A, B, C, D, C’, B’, A’, where “D” serves as a single pivot saying). The total number of steps may vary, but each step should balance its offsetting partner in length. That is, if step B consists of one saying, but the balancing B’ contains three sayings, the palistrophe may be an invention of the reader, not indigenous to the text. Palistrophes operate in Proverbs 1:11–18, again in 22–33, and also in 8:5–21.

E. Problem-plus-resolution

A problem-plus-resolution offers the last feature fostering internal coherence. As an example, unwise financial risks present a problem in Proverbs 6:1–2, followed by the sage’s solution in verses 3–8. The lure of promiscuity comprises the problem in 5:3–6, followed by solutions both negative (the young man should keep far from the “strange woman,” vv. 7–14) and positive (he should be devoted to his wife, vv. 15–20).

3. Second-guess seeming discontinuities

What about cases of seeming discontinuity? What should we make of situations where, despite outer borders that suggest several sayings belong together, within those boundaries an apparent discontinuity of topic or theme separates one saying from the next?

A. Study the target saying

Two steps must be taken in such cases. The first requires us to carefully study the target saying from multiple angles. Instead of concluding prematurely that the saying is out of place, we must slowly rotate it, like a faceted gem, and ask ourselves what aspect of this saying may have moved the sage to link it with what precedes and follows. At times, the clue emerges from something the sage said, not only in adjacent sayings, but multiple sayings earlier within the same poem.

As an example, consider the masterful lecture diagnosing the consummate evildoer (Prov 17:4–19:9). The primary lessons of that poem (17:4–18:22) conclude with this observation:

He who has found a wife has found what is good, and has obtained approval from the Lord. (Prov 18:22)

Since the topic of marriage has not appeared earlier in this lecture, and since this particular saying contains no mention of the evildoer or related behavior, at first glance it seems out of place. It seems to have no connection with the poem within which it appears.

However, further reflection reveals that, although marriage was not mentioned earlier, the poet has lifted up rich family bonds as the desirable alternative to evil conduct. In fact, that winsome alternative was established very early in the poem: “Grandchildren are a crown for the elderly, and splendor of sons is their fathers” (Prov 17:6). Add to this the fact that a fundamental trait of the evildoer centers in greed, which has rendered him a “loner” (18:1). On these bases (i.e., the desirability of family bonds and the hazard of being a loner) the appearance of a “wife” in 18:22 emerges as precisely the antidote for the evildoer. For in order to build a rich and resilient marriage, he will be obliged to begin caring beyond his greedy core, effectively dismantling his penchant for self-serving cruelty.

Instead of concluding prematurely that the saying is out of place, we must ask ourselves what aspect of this saying may have moved the sage to link it with what precedes and follows.

What remains in the evildoer poem (after the saying about “finding a wife”) amounts to an appendix. It continues the concept of loneliness, but explains that some loneliness results not from self-centered greed, but from social rejection (Prov 18:23–19:9). This shift of focus beginning at 18:23 indicates that the sage has strategically positioned the saying about “finding a wife” in verse 22. It stands as a climactic conclusion to the primary teaching about the evildoer.

B. Detect deployed proverbs

The second strategy when weighing apparent discontinuity is to detect deployed proverbs. When a speaker or writer wishes to clinch an argument, he or she may deploy a wise saying for persuasive effect. The connection between the deployed saying and the surrounding argument will lie in the saying’s underlying lesson, not in the surface vocabulary.

Thus, when Bildad wanted to convince Job of the cause/effect relationship between his suffering and his supposed prior sinning, he deployed a saying about a papyrus plant (Job 8:11). For, as all would readily admit, a papyrus requires marshy soil (the prior cause) in order to sprout up (the effect). Seeming discontinuity (Bildad’s discourse did not deal in botany) is resolved since the theme of the discourse (the reliability of cause/effect relationships) matches the underlying meaning of the deployed proverb.

In Proverbs, the poem refuting the gang’s overtures (Prov 1:10–19) includes a deployed saying (1:17). On its surface, that saying deals with hunting birds—quite in contrast to the theme of the surrounding poem. Seeming discontinuity resolves as we consider the fowler’s saying’s underlying meaning. The sage teaches that if the youth were to decide to join with the murderous gang, he must possess less brains than do birds. For they, at least, have sense enough to sidestep a net which was spread before their watching eyes. Not so the net-spreading thugs. Into their own net they will rush headlong!

Use Logos’s Bible Outline Browser to compare how your commentaries outline Proverbs.

4 benefits of discerning the larger poems of Proverbs

What benefits accrue from recovering poems within Proverbs? There are four.

1. Poems reveal richer meaning to their single sayings

Consider how single sayings reveal richer meaning when read in context with neighboring sayings. To a substantial degree, meaning arises out of context. Once it is illuminated by themes and expressions at work in its host poem, a single saying will disclose connotations that would go unseen when read only in isolation. Recall how the climax was the impact of “finding a wife” (Prov 18:22), once its relationship to (and strategic position with) the loner-evildoer poem came to light (see above).

2. We discover messages emerging from entire poems or lectures

Consider the benefit of discovering the sage’s cohesive messages, spanning entire poems or lectures. They prove to have been constructed with clearly defined introductions, with sub-points elaborating a central theme, and close with climactic conclusions calculated to drive home the sage’s primary objective for that poem.

As an example, notice the lecture devoted to portraying the height of human flourishing (Prov 20:5–21:4). After a profound wisdom commendation in 20:5, the sage anchors faithful love as the elusive foundation for human flourishing:

Many a mortal may proclaim, “A person consists of his faithful love.” But a person characterized by faithfulness, who can find? (Prov 20:6)

Then follows a triple-theme introduction, mapping out the nature of such “faithful love” through three zones of life (Prov 20:7–9). The next three sections expand—in sequence—those same three zones (20:10–23, 24–28, and 20:29–21:2). In those expansions, it becomes clear that the zones correspond to the successive seasons of one’s life: youth, the years of one’s prime, and later years. The poem’s closing quatrain reverberates with ethical impact: “Executing morality and justice is more preferable to the Lord than sacrifice” (21:3, reminiscent of Samuel’s solemn caution to Saul in 1 Sam 15:22). That quatrain concludes by cautioning against arrogance (Prov 21:4).

3. Adjacent poems cluster together to deliver a cumulative lesson

As we identify themes that dominate whole poems, we are able to notice how clusters of adjacent poems collaborate to deliver a distinct lesson.

Take, for example, the progression of thought moving from one poem to the next across Proverbs 25–29. Taking our cue from scenarios that the sages address in these poems, the audience envisioned for this portion has advanced beyond the level of prospective pupils who must be convinced that wisdom is worth pursuing. (For such was the audience for chs. 1–9.) Further, the audience of chapters 25–29 has matured beyond the level of apprentice sages who need instruction concerning wealth, security, and how to find deep satisfaction and resilient joy. (Such was the audience intended for chs. 10–24.) Instead, those for whom the poems of chapters 25–29 were designed have actually begun to shoulder responsibilities within the community, whether serving as advisors to the monarchy or serving as the monarch.

The progression of thought across the four poems of Proverbs 25–29 unfolds in the following manner.

- An introductory lecture sets forth the program for this group of poems: to enable two sorts of leaders to raise their nation from mediocrity to magnificence (25:1–12). The two sorts of leaders specified in the introduction are kings and their courtiers or advisors.

- After the introductory lecture, the second poem focuses on courtiers and their role in raising the land from mediocrity to magnificence (Prov 25:13–27:22).

- The third poem bridges between courtiers and kings, drawing lessons of leadership from animal husbandry (27:23–27).

- This division of Proverbs (25–29) closes, predictably, with a fourth lecture primarily directing monarchs along a path leading out of mediocrity and into magnificence (28:1–29:27).

The four-lecture division concludes with a saying steeling leaders never to quit the field in the interminable struggle against evil (29:27).

From so powerful a poem-by-progression stretching across Proverbs 25–29, one can register the substantial benefit that accrues as we recover the cumulative message delivered by the sages through a cluster of related lectures.

4. A book-wide curriculum of wisdom training comes into view

A fourth benefit emerges as a book-wide grasp of Proverbs enables us to distinguish between foundational, intermediate, and advanced topics suitable for wisdom instruction. A high-altitude view of Proverbs according to its four divisions discloses a broad and escalating curriculum in wisdom training.

- These four divisions begin with the novice training of Division I (Prov 1–9; notice mention of named author in 1:1), lessons that invest considerable energies convincing youth that training in wisdom deserves their enrollment.

- In the apprentice training of Division II (Prov 10–24; notice mention of named author in 10:1), we discover less time spent convincing youth to enroll. More time is spent on topics having popular appeal, such as how to get rich. Division II lectures then transition to more needful topics: how to become secure, how to lead, how to truly flourish, how to transmit wisdom to others.

- In Division III (Prov 25–29; notice mention of authorship in 25:1), more advanced instruction is reserved for pupils who have begun to serve in positions of community responsibility. Here kings and courtiers learn to lift their realm from mediocrity to magnificence, closing with monarchial instruction.

- The sage in Division IV (Prov 30–31) returns both to simpler style (poems here present easily discernable borders) and foundational topics, elevating reverence and censuring greed in Proverbs 30 (reminiscent of basic lessons found in Division I). In chapter 31, the author offers instruction for royalty (Prov 31, reminiscent of the close of Division III). This closing poem fittingly concludes the entire curriculum, portraying in the resourceful wife, a likeness of Lady Wisdom, whom the youth should pursue, not momentarily, but as a lifelong partner (Prov 31:10–31).

By thus comparing the successive divisions of Proverbs, there comes into view the sage’s progressive curriculum in wisdom training. This curriculum can instruct us as well in how to cultivate and transmit wisdom today.

Conclusion

The Israelite sages’ love of riddles shines through the wisdom they bequeathed to us. Their riddles range from the smallest single saying, extending to lecture-long poems, reaching as far as book-wide curricular schemes. Only by probing these riddles can we unlock the full riches of life lessons stored for us in this remarkable book.

Paul Overland’s recommended resources for further study

- Heim, K. M. Like Grapes of Gold Set in Silver: An Interpretation of Proverbial Clusters in Proverbs 10:1–22:16. Walter de Gruyter, 2001.

- Meinhold, A. Die Sprüche. 2 vols. ZBK. Theologischer Verlag, 1991.

- Plöger, O. Sprüche Salomos: Proverbia. BKAT 17. Neukirchener Verlag, 1984.

- Whybray, R. N. Proverbs. New Century Bible Commentary. Eerdmans, 1994.

Proverbs (Apollos Old Testament Commentary | AOT)

Save $7.75 (25%)

Price: $23.24

-->Regular price: $30.99

The Anchor Yale Bible: Proverbs 1–9 (AYB)

Save $4.01 (10%)

Price: $35.99

-->Regular price: $35.99

Anchor Yale Bible: Proverbs 10-31 (AYB)

Save $6.01 (10%)

Price: $53.99

-->Regular price: $53.99

Proverbs, 2 Volumes (New International Commentary on the Old Testament | NIC)

Save $27.99 (23%)

Price: $89.99

-->Regular price: $89.99

Consider Logos’s commentary collections on Proverbs

Best Proverbs Commentaries (7 vols.)

Save $39.44 (16%)

Price: $194.99

-->Regular price: $194.99

Proverbs Commentaries: Exegete (5 vols.)

Save $39.96 (16%)

Price: $200.99

-->Regular price: $200.99

Proverbs Commentaries: Exposit (5 vols.)

Save $23.46 (20%)

Price: $89.99

-->Regular price: $89.99

Proverbs Commentaries: Apply (5 vols.)

Save $16.96 (19%)

Price: $67.99

-->Regular price: $67.99

Related articles

- Everything You Need to Know for Preaching Proverbs

- Get Them to Call It “Wisdom Literature”: A Screwtape Letter

- 9 Commentaries on Wisdom Literature (& Why It Matters)

- The Meaning of Ecclesiastes | Bobby Jamieson

- Is the Song Allegorical? | Fellipe do Vale on Song of Solomon

1 month ago

34

1 month ago

34

English (US) ·

English (US) ·