Gerald Bray’s Athens and Jerusalem– Part Eight 2025-04-04T16:36:45-04:00 Ben Witherington

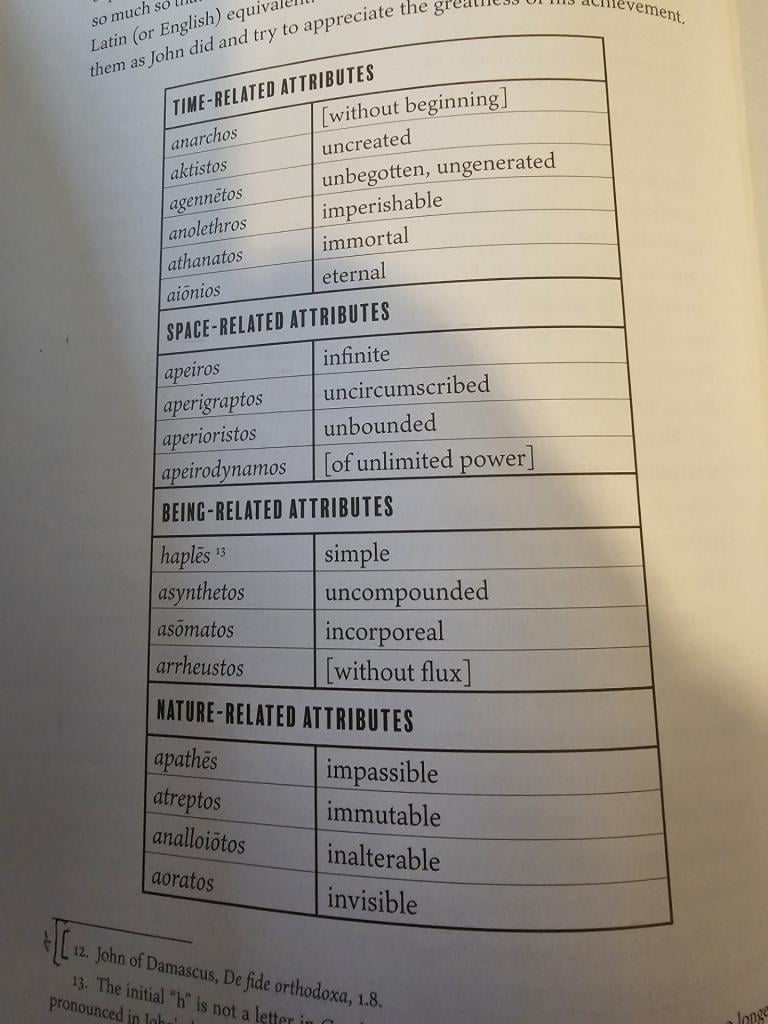

According to Gerald Bray, the first real systematic theologian of the Christian church was John of Damascus (675-750). He lived under Muslim rule in Syria and then Palestine as well. He was a leading critic of iconoclasm, which was the movement to destroy images on the basis that it was a sacrilege to represent God in images, since God is spirit. But as John was to argue, there couldn’t be images of the divine nature since it is invisible, but rather images of God in flesh in the person of Christ. This was based on the notion of enhypostasia, that the Son didn’t just appear to be human but was genuinely incarnated in the flesh. But as John went on to say it is possible to enumerate the divine attributes of God following the via negativa which tells us what God is not (the so-called apophatic approach. Here is Bray’s very helpful summary chart (p. 108):

We have already spoken of some of the problems with the term impassible especially if it is taken to mean without pathos or emotions— which is not true of the God of the Bible, but the term immutable, if it means without a change in God’s moral character is fine. But certainly the incarnation reflects an ontological change in the second person of the Trinity who adds humanity to his divine identity. Nevertheless, John took us a significant step forward in systematics and was right to say “philosophy is love of wisdom, and true wisdom is God; therefore the love of God is the true philosophy” (Dialectica 136-37 as quoted by Bray p. 109).

One of the things that became apparent over time was that theologians who leaned more on Plato tended to be realists, in the sense that they believed there really was a blueprint or idea for humanity at least in the mind of God, of which individual humans were manifestations of that paradigm in different ways, but for those theologians following Aristotle, they were nominalists (from the word for name) who did not believe there was a generic pattern human , but rather human is just a term or name for a group of similar beings. One encounters only individual persons, not a generic HUMAN. But is there not something to the phrase ‘we share a common humanity’ even though one can also say there is enormous diversity among humans. This sort of distinction becomes important when comparing humans with other higher orders of creatures, such that humans can always be distinguished from say monkeys, or apes, or dolphins etc. But from a theological point of view the most important distinction is that humans are created in God’s image, unlike the lesser creatures. Perhaps the most famous of the medieval nominalists was William of Ockam.

As Bray comments, the irony is that what we mean by real today, is the opposite of what that term meant in the middle ages, which was ‘the ideal’ for blueprint for the mundane examples of ‘the ‘real’. Nominalism in this sense rules today. Ideas are not seen as ‘real’ indeed they may be fictions or false ideas, but material objects are seen as real.

Bray’s judgments on iconoclasm (p. 107) are right on target. Images of Christ and the saints do not amount to idolatry, but on the other hand the Eastern theology that divine energies could work through icons to produce healing etc. (in other words a form of magic) was going too far. Today what one usually hears that icons are windows on heaven, that gives one a picture of the glorious character of heavenly worship and those involved in it.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·