In his work On Friendship, the philosopher Alexander Nehamas observes that friendship begets the most complicated emotions, from “joy and contentment … to affliction and misery.”1 We can think of Augustine’s famous stolen pears story which led him to realize that friendship can be a dangerous enemy (Conf. 2.8.16–2.9.17), to the more recent literary humanist E. M. Forster, who said, “If I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country.”2. Friendships, truly, rearrange our world.

And this is uniquely true for pastors.

Recent studies on pastoral resiliency have brought to the forefront the impact that loneliness has on pastors and pastoral burnout. Many pastors admit to having few friends whom they can truly open up to. Anecdotally, I have known many pastors who have sought friendship within their church only to find that it creates a risk dynamic that comes with great cost, either driving parishioners away from their church or driving pastors deeper into loneliness and confusion within their ministry. Whether it is due to a pastor’s own emotional neediness, or the parishioner’s inability to handle their pastor’s burden, the results have not been promising—both for the pastor or the parishioner.

Should pastors seek out friendships among those whom they are called to shepherd, or is it wiser to look elsewhere? What do the Scriptures and the Christian tradition have to say? These types of questions are the focus of this article.

First, we will consider what friendship is according to Scripture and with insights from the Christian tradition. After that, we will turn more directly to our question: Should pastors be friends with members of their own local church?

Table of contents

1. The Bible & friendship

All of us enjoy a variety of social arrangements that we bring into the local church—from marriage, parenthood, siblings, citizenship, and so on. The New Testament does not annihilate these social arrangements but elevates them, even as it relativizes them. For example, the New Testament reframes marriage typologically, with Christ as a husband and the church as a bride (Eph 5:25–33); it holds sibling relationships now in relation to Christ (Mark 10:29–30); it anchors our true citizenship in heaven (Phil 3:20). All of these social arrangements exists within an already/not yet matrix: Some will have continuity between the present age and the age to come, while others will fully give way to the age to come—“For when they rise from the dead, they neither marry nor are given in marriage, but are like angels in heaven” (Mark 12:25).

Friendship is one such social arrangement that the Scriptures never speak to directly. Never once are we commanded to be friends with anyone, but we are commanded to love our brothers and sisters in Christ (John 13:34–35), love our wives as Christ loves the church (Eph 5:25), love our neighbors as ourselves (Mark 12:30–31), and love our enemies (Matt 5:43–48).

Nonetheless, while the Bible has zero imperatives related to friendship, it does speak very tenderly about friendship. So what can we learn about friendship from various passages in the Old Testament and New Testament. More specifically, what can we say about the possibility of pastors enjoying friendship in their local church?

The Old Testament on friendship

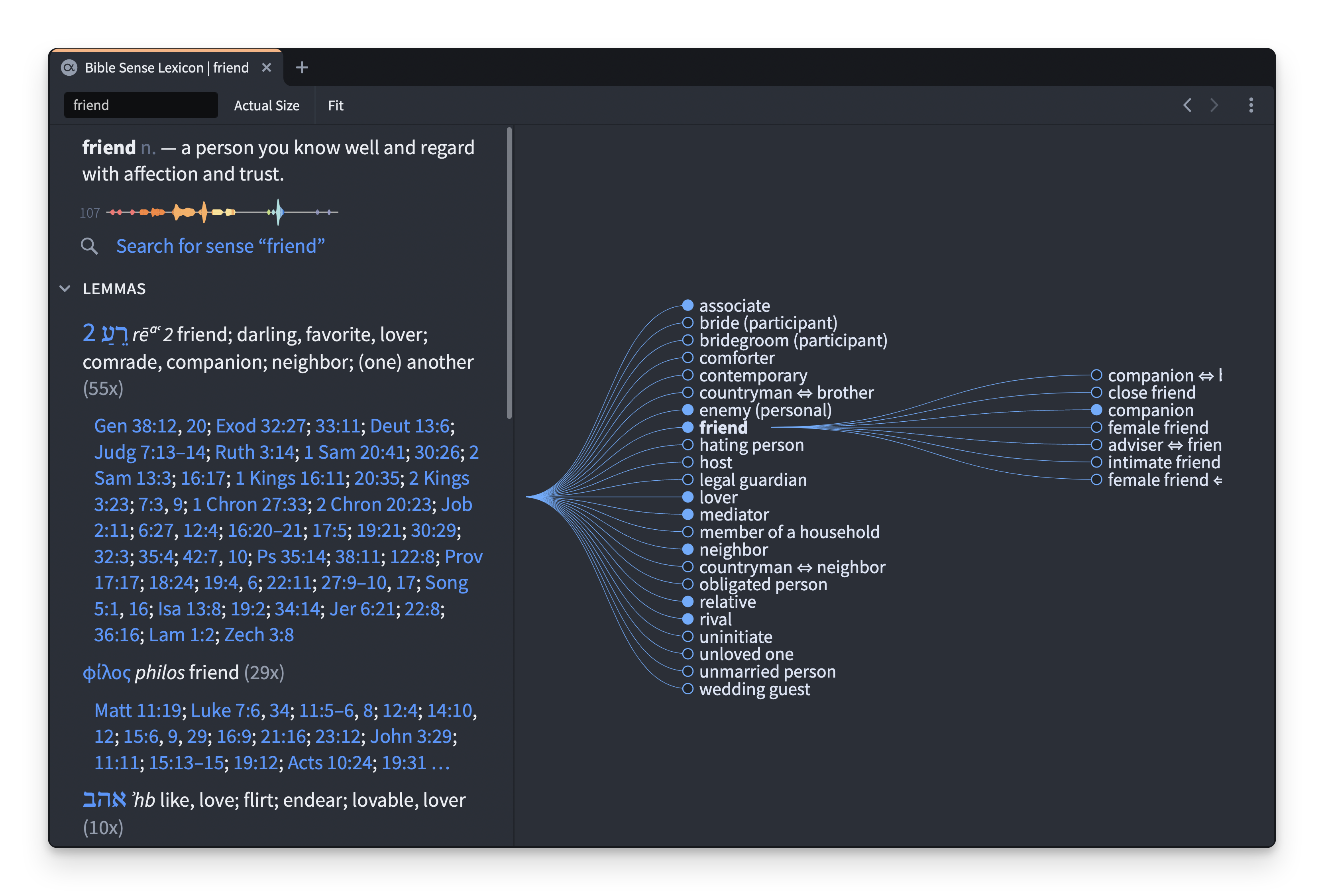

In the Old Testament, friendship is variously expressed through emotional, social, political, and material aspects. The most common terms associated with friendship are רֵעַ and its related words (Lev 19:18; Judg 14:20; 2 Sam 3:8; 16:16–17; Ps 35:14; Job 6:14; Prov 17:17; 27:9), which broadly speaking is defined as a close associate with whom one has a reciprocal relationship. Another important expression of friendship is the Hebrew noun חָבֵר, which is derived from the verb חבר, (“to join”), often used in the context of forming political alliances (e.g., Gen 14:3). The noun חָבֵר refers to a person with whom one is associated or allied, though it does not necessarily carry a political meaning (e.g., Ps 45:7; 119:63; Prov 28:24). The related Aramaic word חֲבַר is used to describe Daniel’s companions—Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah—in Daniel 2:13–18.

A moving example of friendship in the Old Testament is that between David and Jonathan—two men who found each other both enmeshed in the early days of Israel’s monarchy. In 1 and 2 Samuel, we see the following qualities between these two men: tender emotion, intimacy, open communication, loyalty, and unmotivated kindness. Interestingly, their friendship is described not with the noun רֵעַ, as one might expect, but with the verb אהב (“to love”): “The soul of Jonathan was knit to the soul of David, and Jonathan loved [אהב] him as his own soul” (1 Sam 18:1; cf. 20:17). Three times in 1 Samuel, we read that Jonathan loved David “as his own soul” (18:1, 3; 20:17). And then in 2 Samuel, David says of his dead friend, “I am distressed for you, my brother Jonathan; very pleasant have you been to me; your love [אַהֲבָה] to me was extraordinary, surpassing the love of women” (2 Sam 1:26). While the central theme of friendship we see between David and Jonathan is covenant faithfulness, highlighted by the Hebrew word חֶסֶד (ḥesed) in 1 Samuel 20, it is ultimately their lived experience of love towards one another within the monarchal struggle that makes this truly a friendship.

The key ingredient of friendship we see here is what we today call reciprocity, which is the back and forth exchange of truly entering into the sorrows and joys of another person because we know that person can also enter into our same sorrows and joys. Reciprocity, as we will see, is one of the key dynamics we have to ask about between a pastor and parishioner: Can it exist at the level of friendship?

Use Logos’s Bible Sense Lexicon to uncover words related to concepts like friends.

Jesus on friendship

When we turn to the New Testament, the concept of friendship (φιλία) is closely tied to the Greco-Roman patronage system of the first century AD. Friendship within this frame was seen as a reciprocal relationship between two individuals who were social equals, marked by the exchange of services, mutual loyalty, and intimacy. Even though patrons were typically of a higher social status, they would often refer to their clients as friends (φίλος, philos). Regardless of social rank, the defining characteristic of friendship was the expectation of reciprocity. This concept of reciprocity makes it all the more remarkable that Jesus enjoyed friendship with his apostles (John 15:15) and sinners (Luke 7:34)!

In John 15:13–15, we see three key aspects of friendship highlighted by Jesus.

First, he shows us that love (ἀγάπη, agape) shown through sacrifice is central to friendship. We see this in verse 13. “Greater love has no one than this, that someone lay down his life for his friends [φίλος].” Friendship, according to Jesus, entails self-donation. You know a true friend when you meet someone who doesn’t just give you what you need, but in the truest sense gives you themselves and will risk themselves for you—even their reputations, which explains Jesus’s friendship with tax collectors and sinners (Matt 11:19). Friends donate themselves freely. They are unguarded.

Friendship, according to Jesus, entails self-donation. You know a true friend when you meet someone who doesn’t just give you what you need, but in the truest sense gives you themselves.

Second, Christ shows us that his true friends are those who obey his commands. “You are my friends [φίλος] if you do what I command you” (v. 14). While there is a particular asymmetry that Jesus has with us that we don’t have with others (he is Lord in all relationships), obedience is a rich component in all friendships. Friends obey one another when they seek to please one another, which makes the bond all the stronger. The bond aims to be both pleasable and unbreakable, and it grows in its strength when it is mutually experienced.

Finally, we see that Jesus calls his disciples friends because they have been made aware of something that he has not told anyone else. “No longer do I call you servants, for the servant does not know what his master is doing; but I have called you friends [φίλος], for all that I have heard from my Father I have made known to you” (v. 15). That is, I have just told you a divine secret. In this case, his apostles have been made aware of God’s will for the Messiah that lies on the horizon. Analogous to what we know about all true friendships, Jesus is saying a friend is someone who lets you all the way in and tells you his or her secrets. Friends are unbuffered.

In summary, we are seeing that friendship according to Jesus entails an unguarded, unbreakable, unbuffered bond with others. Depicted in both the Old and New Testaments, friendship is not a casual relationship but a deep, voluntary bond that influences all aspects of life, founded upon the gift of reciprocity.

If reciprocity, then, is one of the central aspects of friendship, we will eventually have to ask: Is it realistic—or wise—for pastors to share in this level of friendship with those they are called to shepherd?

2. The Christian tradition & friendship

Moving beyond the New Testament, there is much to glean from the Christian tradition on friendship among clergy. From the friendship of Basil and Gregory, to Ambrose’s expectation of his clergy to cultivate friendships with one another, to Augustine’s routine travels to see friends, to Heinrich Bullinger’s and John Calvin’s friendship at the heart of the Reformation, to Charles Spurgeon’s friendship with the former slave Thomas Johnson, to the eloquent writings of C. S. Lewis, the Christian tradition offers us a lot of wisdom.

Here we will just consider Ambrose, Augustine, and C. S. Lewis—two pastors and one parishioner.

Ambrose on friendship

Ambrose wrote three books On the Duties of the Clergy. In book 3, Ambrose wrote,

Do not desert a friend in time of need, nor forsake him nor fail him, for friendship is the support of life. … If friends in prosperity help friends, why do they not also in times of adversity offer their support? Let us aid by giving counsel, let us offer our best endeavours, let us sympathize with them with all our heart. If necessary, let us endure for a friend even hardship. … Preserve, then, my sons, that friendship ye have begun with your brethren, for nothing in the world is more beautiful than that.3

At the heart of Ambrose’s vision for his clergy was the double gift of pastor and friend. Mike Aquilina reflects on Ambrose’s strong admonitions to his clergy in his book Friendship and the Fathers,4 highlighting that while bishops are the chief pastor to pastors, bishops like Ambrose understood that their role was to cultivate a synodical culture where clergy could exists as both friends and pastors to one another. It’s one thing for pastors to show pastoral decorum with each other, it’s another thing for pastors to show friendship.

Pastors, under Ambrose, did not merely debate and decide on church matters, but they related to one another the way parishioners related to them. Pastoral fidelity and longevity was rooted in reciprocity among pastors holding friendship with one another. Again, Ambrose says, “It is indeed a comfort in this life to have one to whom thou canst open thy heart, with whom thou canst share confidences, and to whom thou canst entrust the secrets of thy heart.”5

Not said explicitly, but we might assume, clergy enjoyed friendship not within their local congregation, but within their local diocese, which is a consortium of priests who shepherd parishes in a particular region. Within my own Anglican tradition, we have a diocese that consists of priests overseeing many parishes throughout the western part of the US. Some of my deepest bonds come from these relationships with other clergy who “get” what I am experiencing.

Augustine on friendship

Peter Brown narrates in his biography on Augustine6 that in the final season of his life, he evidently traveled for two primary purposes: theological consultations and to visit friends. Matters of faith and friends were all that mattered to him in the end.

Even in his own preaching, he understood the value of friendship for his own people, for “[i]n this world two things are essential: a healthy life and friendship. God created humans so that they might exist and live: this is life. But if they are not to remain solitary, there must be friendship.”7

In his most personal work, the Confessions, Augustine says,

You only love your friend truly, after all, when you love God in your friend, either because he is in him, or in order that he may be in him. That is true love and respect. There is no true friendship unless You weld it between souls that cling together by the charity poured forth in their hearts by the Holy Spirit.8

As it pertains to his own life, we see how central his friends were to him on three occasions. First, with his lifelong and best friend, Alypius, we see friendship expressed as “where you go I will go, and where you lodge I will lodge. Your people shall be my people, and your God my God” (Ruth 1:16). Like Augustine, Alypius was at one time a Manichean, and the two friends were both converted to the Catholic faith and baptized together by Ambrose in 387. Alypius later became a member of Augustine’s first monastery in Tagaste. When Augustine was ordained a priest in Hippo, and founded a community in that city, Alypius joined him there and was subsequently ordained bishop of Tagaste around 384. Augustine praised Alypius, whom he called “the brother of my heart.”9 Whether it was Augustine who influenced Alypius or Alypius who influenced Augustine, it is hard to know. As James K. A. Smith notes in his On the Road with Saint Augustine, friendship and personal identity for Augustine run in the same grooves, the “rutted paths worn by others become the easiest way to go. And so I go with the flow and live someone else’s life.”10

Second, with the famous unnamed friend in Confessions, Augustine writes movingly about this friend falling ill, converting to the faith, and then being quickly baptized. Augustine, still unconverted, recounts visiting his sick friend:

And I did this as soon as he was able, for I never left him and we hung on each other overmuch—I tried to jest with him, supposing that he also would jest in return about that baptism which he had received when his mind and senses were inactive, but which he had since learned that he had received. But he recoiled from me, as if I were his enemy, and, with a remarkable and unexpected freedom, he admonished me that, if I desired to continue as his friend, I must cease to say such things.11

Striking here is how this friend placed a wedge between Augustine and himself as it related to his new life in Christ. Friendship was being relativized before Augustine in relation to Christ, which becomes a significant feature of friendship for Augustine in the years to come. A few days later, this unnamed friend dies. Augustine falls into what reads like a despair:

My heart was utterly darkened by this sorrow and everywhere I looked I saw death. My native place was a torture room to me . . . And all the things I had done with him—now that he was gone—became a frightful torment. My eyes sought him everywhere, but they did not see him; and I hated all places because he was not in them, because they could not say to me, “Look, he is coming,” as they did when he was alive and absent.12

Lastly, when on the eve of the barbarians’ arrival at the gates, the aged Bishop Augustine lay on his deathbed, encircled by North Africa’s church leaders—many of them once his classmates, now his closest friends. Augustine wanted to face the end with his closest friends around him.

There is no greater consolation than the unfeigned loyalty and mutual affection of good and true friends … the more friends we have and the more dispersed they are in different places, the further and more widely extend our fears that some evil may befall them from among all the mass of evils of this present world.13

This very brief look at Ambrose and Augustine highlights a key dynamic for pastors and friendship. While friendship in the local congregation may or may not be possible, friendship among those who serve in the kingdom is very possible. Most often for pastors, the closest companion may be the pastor down the street or the priest in your diocese. What we are seeing with Ambrose and Augustine is that there is something of a built-in congruence that exists among pastors that makes friendship for them readily available, not directly with those they serve in the local church, but among those who are called to serve the local church.

C. S. Lewis on friendship

In his book The Four Loves, C. S. Lewis dedicates a lengthy and memorable chapter on friendship (philos) that engages a crucial plot point in the history of friendships. What is peculiar about Lewis’s discussion on friendship is how much he believes it has been devalued in the modern world. He writes, “To the ancients, friendship seems the happiest and most fully human of all loves… the modern world, in comparison, ignores it.”14 He goes on, “Few value it because few experience it,” because it is “the least natural of loves; the least instinctive, organic, biological, gregarious, necessary.”15

This alleged devaluing of friendship may strike many of us as odd, especially if we think we have a lot of friends. So we have to ask: What is friendship according to Lewis, and how does this accord with what we’ve observed so far?

Perhaps his most famous quote from Four Loves defines friendship as:

aris[ing] out of mere companionship when two or more of the companions discover that they have in common some insight or interest or even taste which the others do not share and which, till that moment, each believe to be his own unique treasure (or burden). The typical expression of opening friendship would be something like, “What? You too? I thought I was the only one.”16

Key to this definition is the word “discover.” When we “discover” something, we “find” something that was not a given, it is more like a gift.

Lewis restates this definition in another way, saying it arises out of mere companionship when two or more of the companions discover that they have a common love for the same thing which gives birth to love for another. This kind of love, as Emerson said, “Do you love me?” means “Do you see the same truth?”—Or at least, “Do you care about the same truth as me?”17 When we “discover” friendship, we are discovering someone seeing what we see in a similar way that we see it and caring about it the way we care about it. This does not mean we have complete agreement on everything, but it does mean we have complete respect. This discovery becomes a “mutual choosing” of each other because of a common love for the same object.

Lewis understands as a parishioner what Ambrose and Augustine understand as pastors. We could say that Lewis strikes awfully close to what we said earlier: Friendship entails a high degree of reciprocity. You encourage the other person to open up as they encourage you to open up because there is a sense of seeing the same thing. This puts friendship in a sort of catch-22 dynamic—who moves first? It is born of something both reciprocal and vulnerable.

3. Pastors & friendship

We now turn more directly to the question: Can, or should, pastors be friends with members of their own church?

As we have seen, friendship requires reciprocity and vulnerability. But when we consider the pastoral office in the New Testament, we discover that there is clear incongruence in the relationship between pastor and parishioner: Pastors are called to preach (2 Tim 4:2), teach (1 Tim 3:2), administer sacraments (Matt 28:19; 1 Cor 10:16–17), marry (1 Cor 7:39), and bury (Gen 23:19; Matt 8:21). They are also called to give counsel (2 Tim 3:16–17), hear confessions (Jas 5:16), and always hold confidence (Prov 11:13).

Pastors, we could say, experience a built-in incongruence among their people that exists simply by nature of their calling. This incongruence is perhaps why pastors have callings that are so unique that they are to be more highly esteemed for having them (1 Thess 5:12–13), and yet will be judged more strictly if they fail in them (Jas 3:1). Pastors are warned the most severely (Acts 20:28; 1 Pet 5:1–3; 1 Tim 3:1–7), and yet are forgiven the most tenderly (John 21:15–19).

The role of a pastor entails them having and holding very intimate knowledge of the people they are called to shepherd, which is a type of knowledge that is not always, nor appropriately, to be reciprocated back to their people. As Bonhoeffer says, “the pastor only wants to know in order to help,”18 not so he can reciprocate. The pastor’s office of spiritual care “does not exist to declare solidarity but to listen and to proclaim the gospel. Proper distance helps establish proper closeness,” says Bonhoeffer.19

Ultimately, as Bonhoeffer says, “the pastor does not bind anyone to himself at any stage, but only to the Word and Spirit of Christ.”20 The Word and Spirit, we could say, create what we might call an “intimate distance” between the pastor and their parishioner. The pastor knows a lot about their parishioner, but it is not knowledge to be appropriated for closeness to themselves, but so that the parishioner might appropriate closeness to Christ.

The uniqueness of this calling makes friendship in the local church between pastor and parishioner one of the more difficult relationships to navigate. And strikingly, the New Testament is silent on the social arrangement of friendship between pastors and parishioners. While we can draw out valuable insights from Jesus’s friendship with his apostles and the tax collectors and sinners, the asymmetry between him and us must also be preserved. Perhaps we may find more sure footing by seeking to obey the fifth commandment (Exod 20:12), to honor our ancestors of the faith who have gone before us and how they thought deeply about this complex subject.

If we may tie the insights of Ambrose, Augustine, and Lewis together to form a threefold chord (Eccl 4:12), we observe that although it’s not impossible for a pastor to find friends in the local church, it’s also not a guarantee. Maintaining the relationship between pastor-as-pastor to parishioner and pastor-as-friend to parishioner is complex. It will always entail risk (but then again, so do all friendships).

Friendship in the local church for a pastor will always be a gift and not a given. But what is a given is that friendship is always a kingdom reality, regardless of whether it is experienced as a local church reality.

My own story is one of friendships both inside and outside the local church. I can say that one of the greatest gifts I have received in ministry, next to serving the people of God in the church, is a group of pastors I call friends. During long seasons where I had no friends in my own local church, these pastoral friendships have sustained me. There have been seasons where I have enjoyed the gift of friendship in the church, during which these same pastoral friendships have shaped me to be a better friend.

Can pastors have friends in their local congregation? Maybe. Can pastors have friends in the kingdom of God? Absolutely! We aren’t called to be friends with everybody, but we are called to love everybody. Friendship is both unique and necessary for pastors, but where it will be found is not certain.

Bedell’s recommended resources for further study

- Friendship and the Fathers: How the Early Church Evangelized, by Mike Aquilina

- Pastoral Friendship: The Forgotten Piece to a Persevering Ministry, by Michael A. G. Haykin, Brian Croft & James B. Carroll

- Made for Friendship: The Relationship That Halves Our Sorrows and Doubles Our Joys, by Drew Hunter

Saint Augustine: Confessions (The Fathers of the Church)

Save $1.55 (5%)

Price: $29.44

-->Regular price: $30.99

The Four Loves (Audio)

Save $0.70 (5%)

Price: $13.29

-->Regular price: $13.99

Additional works on friendship and pastoral ministry

The Pastor as Friend? Understanding Dynamics of Friendship and Friendliness Within a Pastoral Ministry

Save $0.96 (5%)

Price: $18.29

-->Regular price: $19.25

The Solo Pastor: Understanding and Overcoming the Challenges of Leading a Church Alone

Save $0.54 (5%)

Price: $10.25

-->Regular price: $10.79

Holy Friendships: Nurturing Relationships That Sustain Pastors and Leaders

Save $0.58 (5%)

Price: $10.96

-->Regular price: $11.54

Related articles on practical ministry

- Leading with Repentance: On Pastoring Between Pew and Politics

- Why Protestant Pastors Should Read a Catholic Pope on Pastoral Ministry

- How to Plan a Pastoral Hospital Visit

- Mental Illness and Ministry: A “Whole-Person” Pastoral Approach

- Why Christian Vocation Now Requires Learning About Other Faiths

3 weeks ago

31

3 weeks ago

31

English (US) ·

English (US) ·