Government is a word that we often associate with matters that concern the life of the nation—taxes, infrastructure, defense, and elections. But government is also a critical part of the life of the church.

Jesus had many disciples, but he named twelve men to be his “apostles” (Mark 3:13–15; Luke 6:12–13). These apostles were officers appointed directly by Jesus Christ. They had a special and unique role. They were the foundation on which Jesus would build his church (see Matt 16:18; Eph 2:20; Rev 21:14).

It is through the apostles that Jesus, the king of his church, has provided his church with all that we need to serve him in the world until his return. We no longer have apostles with us in the church. But we do have the Bible that they have given to the church. The Bible is a complete guide for faith and life—everything that God requires a person to believe or to do for salvation is in the Bible (2 Tim 3:14–17).

Part of this apostolic provision for the church in the Bible (and especially in the New Testament) is a form of government for the church. The apostles—by their example and by their teaching—have given us what we need to order our common life as the church. For that reason, we see the two permanent offices of the church—elder and deacon—showing up repeatedly in Acts and the New Testament letters.

In what follows, we are going to ask some basic questions about the two offices of elder and deacon.

- What exactly are they?

- What are the biblical qualifications for the elder and the deacon?

- What responsibilities does Scripture assign to each of them?

- What are some practical considerations that the church has to take into account with its elders and deacons?

- Finally, what does the Bible’s teaching about elders and deacons tell us about Christ’s expectations for leadership in the kingdom of God?

The definition of elders & deacons

First, what are elders and deacons? Let’s take each of those in turn.

Elders would not have been new to the New Testament church. From the beginning, Israel had elders (see Exod 3:16, 18; 4:29). They provided leadership for the people of God under the Old Testament. When the people of God assumes its new form under the New Covenant, elders carry over from Old to New. That is why the New Testament authors mention elders without comment on their origin (see, for instance, the first mention of the church’s elders, Acts 11:30). These are the men whom God gifts and calls to govern the church.

Deacons, however, are an office that is new to the New Covenant people of God. Luke’s account in Acts 6:1–6 gives us the origin of the deacons in the early church. Because of the phenomenal growth of the church, the apostles found that they were no longer able both to “preach the word of God” and “serve tables,” that is, to minister to the needs of widows in the church (Acts 6:2). The apostles would devote themselves “to prayer and to the ministry of the Word” (6:4), while a separate class of officers would take up the work of ministering to the physical needs of the saints (6:3). These men are qualified, elected, and set apart to this ministry (Acts 6:3, 5–6).

The New Testament, then, tells us that there are two standing offices in the church. There are elders (an office of rule or governance) and deacons (an office of service). But we might ask about pastors and bishops—are these not officers in the church, too?

Pastor is a word from the Latin pastor, meaning “shepherd.” The pastor is the spiritual shepherd of the flock. Both Peter and Paul tell us that all elders are shepherds in the church (Acts 20:28; 1 Pet 5:1). But most churches have at least one elder who devotes himself full-time to the public preaching and teaching of the Word of God. Timothy seems to have been just such a man in Ephesus (see 1 Tim 4:11–16). Timothy was an elder serving among other elders. But he was distinct among them as the pastor (or “teaching elder”; see 1 Tim 5:17) of the church.

Some churches have bishops. These are individual officers who preside over the churches in a district and have authority to make decisions about those churches and the pastors who serve those churches. We do not find bishops like this in the New Testament. Rule or governance of the church is never committed to a single ordinary officer, but always to elders acting together (see Acts 11:30; 15:2; 21:18). That is why each congregation in Scripture has a plurality of elders (Acts 14:23; Phil 1:1).

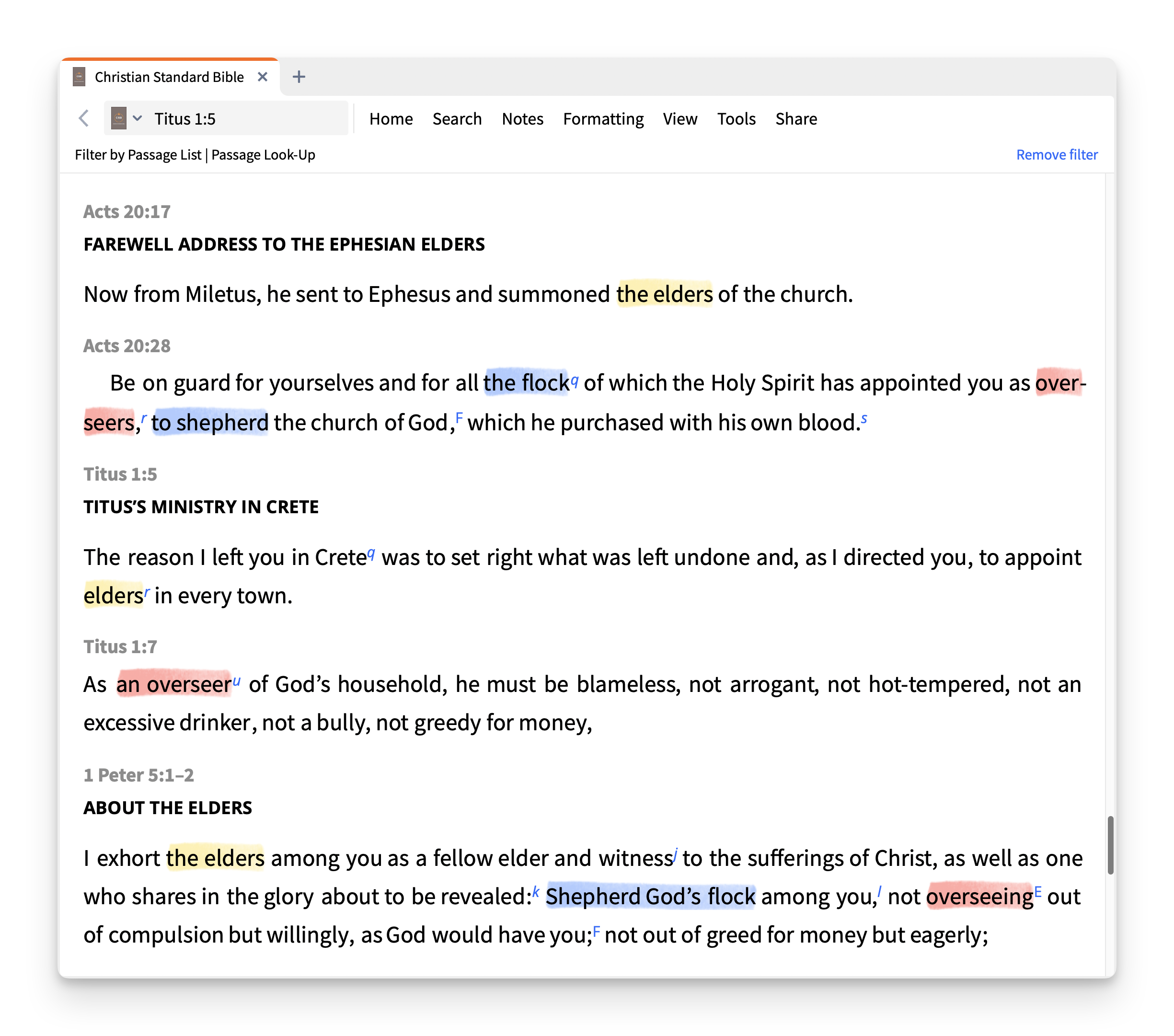

But every elder is a bishop in another sense of that word. The word bishop means “overseer.” Every elder is an “overseer” of the people of God (cf. Titus 1:5; 1:7; Acts 20:17; with Acts 20:28). However many elders a congregation has, that’s how many bishops it has!

Acts 20, Titus 1, and 1 Peter 5 use elder, overseer, and pastor interchangeably

The qualifications of elders & deacons

The New Testament provides us lists of qualifications for elders in 1 Timothy 3:1–7 and Titus 1:5–9, and for deacons in Acts 6:3 and 1 Timothy 3:8–13. What do these lists tell us?

First, the New Testament tells us that the offices of elder and deacon are reserved only for men (see 1 Tim 2:12; 3:1; Acts 6:3; although some appeal to Rom 16:1 and 1 Tim 3:11 in saying that a woman may serve as a deacon in the church). This is not because the New Testament teaches that men are superior to women (it doesn’t—see 1 Cor 11:11–12). Nor is it because women are categorically forbidden from ever teaching and serving within the church (they aren’t— see Tit 2:3–4; Acts 18:26; 9:36, 39). Rather, it is because of the order that God has set within the church—one that extends back to the creation of our first parents, Adam and Eve (1 Tim 2:11–15).

A second thing that these lists tell us is that character matters. While an elder or deacon must have certain gifts to serve the church, it is not enough to be skilled or successful in the tasks of each ministry. An officer must demonstrate a consistent, godly character in all areas and departments of his life. In fact, almost all of the qualifications for each office in 1 Timothy 3:1–13 concern the candidate’s character—his control over his passions, speech, and finances (3:2–3, 8); his relationships both within the church and outside the church (3:7); and his management of his own household (3:4–5, 12).

Each officer must particularly demonstrate character in relation to the work of his office. Because elders shepherd and teach (1 Tim 3:2), they must do so in humility and patience (Titus 1:7), and not out of greed or in anger (1 Tim 3:3). Because deacons often handle and disburse money, it is especially important that they are honest in speech and free from the love of money (1 Tim 3:8).

Why does character count so much for the church’s elders and deacons? One reason is that every officer is an example of Christian speech and conduct to the whole church. Church officers model to their fellow Christians the way in which all Christians must follow Christ (1 Tim 4:12; 1 Pet 5:3). They must be able to say to their fellow Christians, as Paul did to his fellow Christians, “Be imitators of me, as I am of Christ” (1 Cor 11:1).

The responsibilities of elders & deacons

While character is paramount, men must have certain recognized gifts in order to step into the office of elder or deacon.

These gifts—like all gifts in the church—proceed from God (particularly, God the Spirit; see 1 Cor 12:4–11). Thus, no gift is ever cause for boasting in oneself (1 Cor 4:7). Gifts, rather, are given to serve others by edifying the body (see 1 Cor 14:3–4). The gifts that God assigns to elders and deacons are designed to build up the church when they are put to proper use. Let’s look at how that happens.

As we noted above, all elders are called to serve as spiritual shepherds in the church. That work primarily happens through teaching the Word of God. For this reason, all elders must be able to teach (1 Tim 3:2). Teaching is not simply what happens in the pulpit on Sunday morning. It is also leading a Sunday school class or a home Bible study, offering Christian counsel to a family, or sharing Christian wisdom with a younger believer. It is in light of this ministry of teaching the Word of God that believers are called to “obey” their elders and “submit” to them (Heb 13:17). This ministry is what Jesus envisions in the Great Commission—teaching “them to observe all that I have commanded you” (Matt 28:19, emphasis added). Elders do not simply tell people what the Bible says. They also urge them to observe it in their own lives.

This spiritual enforcement of the Word of God will mean that the elders of the church must sometimes gather together and “admonish” people in the church (1 Thess 5:12). Sadly, church members sometimes resist and rebel against the demands of discipleship in their own lives. In such cases, Christ has entrusted a system of discipline to the church that is designed to reclaim the offender and to promote the purity of the church and the honor of Christ (see Matt 18:15–17; 1 Cor 5:1–13). It is the elders who are tasked with the pursuit of straying sheep in hope of their spiritual restoration. They are to do this not in a “domineering” way (1 Pet 5:3), but “in a spirit of gentleness” (Gal 6:1).

There are other tasks that belong to the elders in their gathered capacity. We see elders gathering to make financial decisions for the church (Acts 11:30). We see them gathering in a regional council to refute error and to safeguard the doctrinal purity of the church (Acts 15:1–35). We also see them gathered to set apart other qualified men for the eldership (Acts 13:1–3; 1 Tim 4:14) and the diaconate (Acts 6:6). These various actions, touching on discipline, finance, doctrine, and the admission of men to office (i.e., ordination) are acts of government. The elders undertake them jointly (not individually) and in this way exercise rule in the church (1 Tim 5:17).

Deacons, we saw above, originated from a concrete need in the church—widow care (Acts 6). Paul gives elaborate instructions for the care of widows in 1 Timothy 5:3–16. Surely these were instructions that Timothy was to transmit to the deacons in the Church of Ephesus (1 Tim 3:8–13). A glance at these instructions reveals the authority that deacons have in the church. In particular, deacons are to determine which widows in the church are (and are not) eligible to receive the church’s benevolences.

Deacons serve (the word “deacon” comes from the Greek διάκονος, meaning “servant”), but there is an authority that belongs to that office of service in the church. Although rule or governance belongs to the church’s elders, elders must not prevent or hinder deacons from undertaking the particular ministry to which Christ has called the deacons in the church.

While deacons care for widows, they do not only care for widows. The principle established in Acts 6:1–6 (and reflected in 1 Tim 5:3–13) is that deacons tend to the temporal or this-worldly needs or concerns of the people of God. They serve all kinds of people in the church who are in outward need. They may also tend to any property that the church may own. Although the work of the deacon is, in many ways, physical, it is no less a spiritual act of service. For this reason, deacons must be “full of the Spirit and of wisdom” (Acts 6:3).

Thus, elders and deacons each have authority in the church, but authority for different tasks. As such, these offices and their work are complementary and not competitive. In fact, each office reflects, in its own way, the character and ministry of the Lord Jesus Christ. Elders, when they faithfully teach, preach, and enforce the Word of God, do so as Christ’s representatives (see Eph 2:17; 2 Cor 5:20–6:1; Matt 18:18–20). Deacons remind the church that Jesus ministered on earth as God’s Servant (Matt 12:18–21; 20:28), tending to the needs of others with compassion, sympathy, and humility.

Elders, when they faithfully teach, preach, and enforce the Word of God, do so as Christ’s representatives. Deacons remind the church that Jesus ministered on earth as God’s Servant.

Practical matters relating to elders & deacons

In one sense, everything that we have been discussing is eminently practical—it concerns the day to day life and ministry of the church. But there are some more specific practical questions that we may take up. We will do so under three headings:

- Entering

- Remaining

- Leaving

1. Entering

How do men enter the office of elder and deacon? We have seen that any candidate must have the gifts and character required by the Scriptures for that office. But what else must happen?

First, there ought to be a trial or testing of candidates for office that Paul commits to Timothy (1 Tim 3:10; 5:22). Once candidates have been certified by the elders as eligible according to Scripture (per 1 Tim 3:1–7 or 3:8–13), they should be elected to office by the congregation (Acts 6:3). No man should be placed over a congregation as an elder or a deacon against the congregation’s will. They must ask him to be their elder or deacon. After election, what remains is for the elders to set apart (or “ordain”) that man to office through the laying on of hands and prayer. That act is not sacramental. It is, rather, the elders’ solemn setting apart of a man, admitting him to the office to which he has been called.

2. Remaining

Once a man is ordained to the office of elder or deacon, he ought to continue in that office. Some churches have the practice of term limits for elders or deacons. Whether or not a church has this practice (and there are some good reasons against it, not least the limitations that it places upon the effectiveness of an officer in long-term service in the local church), the officer remains an officer of the church. This is true whether or not he is actively serving a term of office.

Churches typically pay their pastor a salary and benefits, but they usually do not do that for their other elders and for their deacons. The reason for this practice lies in what Paul says to Timothy in 1 Timothy 5:17. Pastors, or “teaching elders,” are “worthy of double honor,” that is, they deserve to be compensated by the church for their labors. (This is the same principle that Paul addresses at length in 1 Cor 9:1–14.) Because they commit themselves vocationally to the work of preaching, those who benefit from their ministry ought to provide them remuneration (Gal 6:6).

3. Leaving

Officers have been admitted by the church to office, and the church may also remove them. Sadly, officers (like other Christians) sin and can sin grievously. This discipline may result in that officer being formally suspended from office or even removed from office. For that reason, they—no less than other Christians—are subject to the discipline of the church (see 1 Tim 5:19–20). The Apostle Paul, for instance, commanded the Church of Galatia to remove the false teachers from their midst (Gal 4:30–31). Such a solemn act is a reminder that holding office is a privilege granted, not an entitlement owed.

The leadership of elders & deacons

It goes without saying that elders and deacons are the leaders that Christ has appointed within and for the church. Because authority and leadership is so subject to misunderstanding and misuse, it is important, as we draw to a conclusion, to reflect on how it is that elders and deacons are (and are not) to be leaders in the church.

Jesus observed—at the Last Supper, no less—his apostles grossly misunderstanding and misusing authority (Luke 22:24). They were jockeying for preeminence, comparing themselves to one another. Jesus makes this sad occasion a teaching moment in the lives of his disciples. Jesus stresses here that our model and paradigm for authority in the church is not the patterns of authority on display in the world around us (Luke 22:25). It is, rather, the person and work of Christ himself (Luke 22:26–27).

One corrective in the church to the misuse of authority is the reminder that authority finds its origin, model, and goal in the Lord Jesus Christ himself. Problems always come when officers look elsewhere for the way in which they exercise their authority in the church. The point is as easily forgotten, it seems, as it is elemental.

We can identify another check or curb to the misuse of authority in the church. Jesus entrusts authority to men who continue to face the reality of indwelling sin (see Rom 7:14–25). Perfection is not a prerequisite for authority in the church. Knowing that, Jesus wisely does not commit governing authority in the church into the hands of a single man. Governing authority, we have seen, is entrusted to the elders jointly. No single man should attempt to wield what belongs to the plurality of the elders in the church.

Furthermore, the New Testament testifies to assemblies of elders at local (Acts 14:23), regional (Acts 20:17; 21:18), and supra-regional (Acts 15:1–35) levels. As the Jerusalem Council demonstrates, a matter can be sent up to the council (Acts 15:1–2) and then resolved by the council (Acts 15:19–21). The council’s decree is then sent down to the churches as something binding upon them (Acts 15:28). This action shows the principle of the mutual accountability of assemblies of elders to one another. These regionally diverse assemblies of elders hold one another accountable in the work to which Christ has called them.

Thus, the New Testament points to two curbs on the authority of elders. One is horizontal (all governing power is jointly exercised). The other is vertical (higher assemblies of elders exercise oversight and control over lower assemblies of elders).

As the New Testament shows us, though, not even in the days of the apostles was the leadership of the church free from sin and the misuse of authority. The solution is not to abandon the idea or exercise of authority (if such a thing were even possible). The solution, rather, is for the church to hold its leadership accountable to the standards of the Bible, including maintaining those checks and balances that Christ has set in place for those fallible men whom he has set in authority.

What the imperfection of even the best of elders and deacons reminds us is that there is only one perfect leader, the king and head of his church, Jesus Christ. No Christian—and certainly not a Christian leader—can ever afford to take his eyes off him. Thankfully, Christ is more than an example to his people (though he is certainly an example to us). He is the merciful and compassionate Savior of sinners. And, in the end, it is Christ who is the great need and help of his church. That glorious reality, in the end, is the leading aim and concern of the church’s government.

Guy Waters’s recommended resources for further study

- The Shepherd-Leader: Achieving Effective Shepherding in Your Church, Tim Witmer

- How Jesus Runs the Church, Guy Waters

- The Elder and His Work, David Dickson

- Elders in the Life of the Church: Rediscovering the Biblical Model for Church Leadership, Newton and Schmucker

Well Ordered, Living Well: A Field Guide to Presbyterian Church Government

Save $4.00 (50%)

Price: $3.99

-->Regular price: $3.99

Church Elders: How to Shepherd God’s People like Jesus (9Marks Building Healthy Churches Series)

Save $0.50 (5%)

Price: $9.49

-->Regular price: $9.99

The Message of 1 Timothy & Titus (The Bible Speaks Today | BST)

Save $0.70 (5%)

Price: $13.29

-->Regular price: $13.99

The Deacon: The Biblical Roots and the Ministry of Mercy Today

Save $0.70 (5%)

Price: $13.29

-->Regular price: $13.99

Additional resources suggested by the editor

The Christian Ministry, with an Inquiry into the Causes of Its Inefficiency, Vols. I & II

Save $0.62 (5%)

Price: $11.87

-->Regular price: $12.49

Sojourners and Strangers: The Doctrine of the Church (Foundations of Evangelical Theology)

Save $1.55 (5%)

Price: $29.44

-->Regular price: $30.99

40 Questions about Elders and Deacons (40 Questions Series)

Save $0.90 (5%)

Price: $17.09

-->Regular price: $17.99

Deacons: How They Serve and Strengthen the Church (9Marks Building Healthy Churches Series)

Save $3.50 (35%)

Price: $6.49

-->Regular price: $9.99

Related articles

- The 16 Best Books on Ecclesiology, Selected by a Theologian

- Ecclesiology: What Do We Believe about the Church?

- Why Protestant Pastors Should Read a Catholic Pope on Pastoral Ministry

- What Are the Keys of the Kingdom? | Jonathan Leeman on Matthew 16:19

1 month ago

36

1 month ago

36

English (US) ·

English (US) ·