“The earliest manuscripts do not have …”

This is how many modern translations introduce Mark 16:9–20 and John 7:53–8:11.

So what is a pastor to do when preaching passage-by-passage through either Mark or John? Do you preach these passages? Do you ignore them? Many in your congregation will be familiar with them and will assume they are part of the inspired Word of God. Skipping over them without comment would be disconcerting. But would discussing the uncertainty of the text undermine your congregation’s confidence in the biblical text?

What should you do?

In this article, I’ll seek to help you answer that question. But before we do, let’s begin by looking at the science and art of what we call “textual criticism.”

Table of contents

What is textual criticism?

Christians are sometimes disturbed to learn that while there is a wealth of ancient manuscript evidence for the text of the New Testament, there are thousands of textual “variants” (different readings) among these many manuscripts. Footnotes in Bibles alert readers to these variants with comments like, “Some manuscripts read …” as they point out omissions, additions, and alternate readings.

While this can be disturbing for Bible readers, it should not surprise us. Before the invention of the printing press in the sixteenth century, all books were copied by hand, a process that inevitably resulted in errors. Indeed, of the more than six thousand ancient manuscripts containing parts of the Greek New Testament, no two are identical.1

While this is technically true, two clarifications are in order. First, none of these variants change any fundamental doctrine of the Christian faith. This is because core beliefs (such as the deity of Christ) are supported by many passages. Second, while absolute certainty concerning the original text of Scripture is unattainable, biblical scholars have developed effective tools to get us very close. The method used is known as textual criticism.

None of these variants change any fundamental doctrine of the Christian faith.

Textual critics examine two kinds of evidence, external and internal. External evidence refers to the manuscripts themselves, their age, relationship to one another, and relative value. In general, older manuscripts are considered more reliable, since they are closer to the originals.

Our oldest New Testament manuscripts are called papyri, since they were written on a paper-like material made from papyrus reeds, which grew in abundance in Egypt. We have approximately 140 Greek papyri of various parts of the New Testament, dating from the second to the fifth centuries AD. They are identified with an Old English “p” followed by the number assigned to that manuscript (e.g., 𝔓45, 𝔓66).

The next oldest manuscripts are the majuscules (also called uncials). These were written on parchment (animal skins) and are named after their block-like style of handwriting. We have over 320 majuscule New Testament manuscripts dating from the fourth to tenth centuries. Our two oldest majuscules are Codex Sinaiticus (ℵ) and Codex Vaticanus (B), both of which date to the fourth century.

The great majority of New Testament manuscripts are called minuscules, named after the cursive or running-style handwriting that gradually replaced the majuscule style beginning around the ninth century. We have over 3,000 minuscule manuscripts of parts or all of the Greek New Testament, as well as almost 2,500 Greek lectionaries: books containing Scripture passages for liturgical reading.

In addition to these Greek manuscripts, external evidence also includes the “versions”: early translations of the New Testament into other ancient languages, like Latin, Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, Georgian, Ethiopic, and Slavonic. It also includes patristic quotations (citations of Scripture made by the early church fathers). Together, this amounts to a massive body of evidence for the New Testament text.

If external evidence refers to the age and value of the manuscripts, internal evidence evaluates the readings found in these documents, seeking to identify changes based on the tendencies of authors and copyists. Copyists tended to alter the text in predictable ways, such as smoothing out difficulties, harmonizing parallel passages, and adding natural complements (like adding “Christ” to the name Jesus). These kinds of changes are usually quite easily recognized by following standard rules of textual criticism. One such rule is that “the harder reading is usually the better one.” This is because a copyist is more likely to smooth out a difficult passage than to make an easy one difficult. Another rule is that “an unharmonized reading is usually better than a harmonized one,” since copyists tended to harmonize parallel passages.

Students of the Word should also be encouraged to learn that the great majority of textual variants are minor ones, related to small issues of style or grammar. In fact, of the many variants found throughout the New Testament, only two are of significant length. By “significant,” I mean more than a sentence or two. These are:

- The longer ending of Mark’s Gospel (Mark 16:9–20)

- The account of the woman caught in adultery (John 7:53–8:11)

In the following discussion, I will briefly examine the textual evidence related to these two passages, as well as discuss how pastors might handle them in their preaching ministry in the local church.

The longer ending of Mark’s Gospel

The textual evidence of Mark 16:9–20

In our earliest manuscripts, Mark’s Gospel ends in a surprising and puzzling manner (Mark 16:1–8).

On Sunday morning following the crucifixion and burial of Jesus, three women come to Jesus’s tomb to anoint his body with spices. To their surprise, the stone sealing the tomb is rolled to one side and a young man in a white robe—presumably an angel—announces that Jesus has risen from the dead. The man tells the women to report this to Peter and the other disciples, and that they should go to Galilee, where they will see Jesus alive. The text ends with the statement that “Trembling and bewildered, the women went out and fled from the tomb. They said nothing to anyone, because they were afraid” (Mark 16:8 NIV). There is no resurrection appearance, no great commission, and no account of Jesus’s ascension.

While our earliest manuscripts end here, the great majority of manuscripts include additional verses which recount three resurrection appearances:

- to Mary Magdalene

- to two disciples “walking in the country”

- to the eleven disciples, whom Jesus rebukes for their unbelief

Jesus commissions them to preach the gospel to all of creation, promises them miraculous powers, and ascends to the right hand of God in heaven. The disciples go out and preach the gospel everywhere, accompanied by miraculous signs (Mark 16:9–20).

There is another, shorter ending that occurs together with the longer ending in four majuscule manuscripts that date from the seventh to ninth centuries. It reads, “Then they quickly reported all these instructions to those around Peter. After this, Jesus himself also sent out through them from east to west the sacred and imperishable proclamation of eternal salvation. Amen.” Although this variant has no claim to authenticity, it confirms that copyists were wrestling with the abruptness of Mark’s ending.

The vast majority of New Testament scholars consider verses 9 to 20 to be a later addition, introduced in the second century by a Christian copyist who was evidently disturbed by Mark’s brusque ending. While most later Greek manuscripts contain these verses, our earliest ones—Codex Vaticanus (B) and Codex Sinaiticus (ℵ)—and some other early witnesses do not. Furthermore, the early church fathers Clement of Alexandria and Origen show no knowledge of verses 9–20, and both Eusebius, the early church historian, and Jerome, the translator of the Vulgate, claimed that this passage was absent from almost all Greek manuscripts known to them.2

View and sort Biblical manuscripts with Logos’s New Testament Manuscript Explorer.

The internal evidence also weighs strongly against these verses.

- The vocabulary and style are dramatically different from what we see elsewhere in Mark.

- The transition from verse 8 to verse 9 is also very awkward. Verse 9 begins with a masculine singular participle referring to Jesus (“having risen”), but Jesus is not named, and the previous verse has the women as its subject.

- The resurrection appearances that follow appear to be summaries from the other Gospels (to Mary Magdalene [John 20:11–18]; to the Emmaus disciples [Luke 24:13–32]; to the Eleven [Luke 24:36–43]; Great Commission [Matt 28:18–20]; ascension [Luke 24:50–51; Acts 1:9–11]).

- In verse 9, Mary Magdalene is introduced as though she were a new character, even though she has been present in the previous three episodes (15:40, 47; 16:1).

- The other two women disappear from the scene, and Mary alone sees Jesus and reports to the disciples (as in John 20).

- Finally, while the angel said they would see Jesus in Galilee (v. 7), the longer ending mentions only appearances in the vicinity of Jerusalem.

Other themes in these verses do not sound like Mark. Speaking in tongues (v. 17) and confirmation of the gospel through signs (vv. 17–20) are more characteristic of the book of Acts than Mark (Acts 2:3–4, 4:30; 5:12; 10:46; 19:6). Picking up snakes (v. 18; cf. Luke 10:19) and drinking poison without harm (v. 18) occur nowhere else in Mark.3

Considering these many factors, the primary debate among scholars is not whether verses 9–20 were original to Mark’s Gospel (they clearly were not), but whether Mark intended to end at 16:8, or whether Mark’s original ending was lost.

How to handle Mark 16:9–20 when preaching

So how should a preacher, preaching passage-by-passage through Mark, handle its ending?

First, we need to start with a clarification concerning Mark’s ending. While it is sometimes said that there is no resurrection in the shorter ending of Mark, this is incorrect!

- Jesus, who is an absolutely reliable character in Mark, has repeatedly predicted that he will rise from the dead (8:31; 9:9, 31; 10:34). From the perspective of Mark’s narrative theology, therefore, Jesus rose from the dead!

- Furthermore, the angel—also an absolutely reliable character in Mark’s story—announces that Jesus has risen from the dead (16:7). There are also resurrection appearances in Mark’s Gospel, even if they are not narrated as part of the story.

- Jesus earlier announced that the disciples would see him alive in Galilee (14:28), and the angel repeats this prediction (16:7).

From Mark’s perspective, therefore, Jesus rose from the dead and was seen alive by his disciples.

So why are there no resurrection appearances narrated? As noted above, there are two main views:

- Mark intended to end at 16:8.

- Mark’s original ending was lost.

Both views are well defended by highly reputable scholars.4

I have gone back and forth on this question but have come to believe that 16:8 was likely Mark’s intended ending. A lost ending seems problematic both historically and theologically.

From a historical perspective, it seems unlikely that the last page of the codex would have been lost before it was copied even once. If Mark had any role in disseminating his Gospel—as church tradition suggests—would he have let it circulate in an incomplete form? If his original was damaged, why not simply rewrite its ending?

For those who believe in the divine inspiration of Scripture, there is also a theological problem. If the Holy Spirit inspired Mark to include resurrection appearances, would God, in his providence, have allowed something so important to be lost? It seems best to conclude that Mark’s Gospel came to us in essentially the form God intended.

We would tentatively (and humbly!) conclude, therefore, that Mark intended to end his Gospel at 16:8. While this ending may seem strange and surprising, Mark’s Gospel is full of strange and surprising things (see, for example, 4:10–12; 6:5; 8:22–26; 11:12–14; 14:51–52). The ending makes good sense if we see the whole of Mark’s Gospel as a call to faith—to respond to the announcement of the kingdom of God: “Repent and believe the good news!” (1:14–15).

In the end, the women experience two things, an empty tomb and the announcement of the resurrection. But how will they respond? With fear and silence? Or by overcoming their fear with faith and proclaiming the message of the resurrection? Mark’s original readers are in the same position. They are experiencing persecution and even the threat of death. They have heard the announcement of the resurrection. But how will they respond? With fear and silence? Or with faith and action, proclaiming the good news?

This is how I would preach this passage:

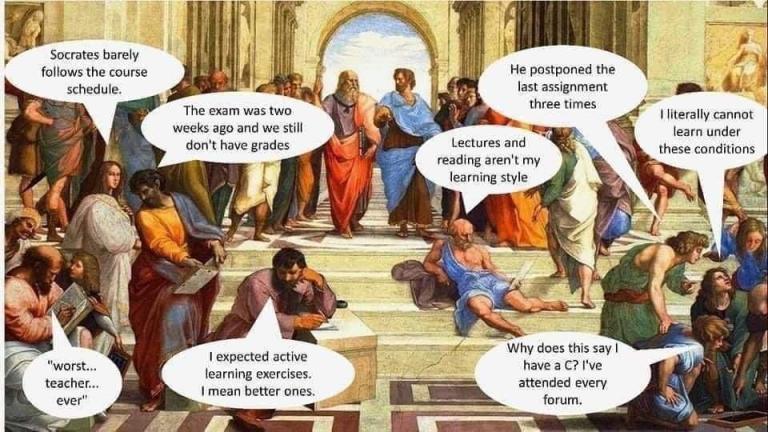

- Take the opportunity to teach your congregation about the reality of textual variants. While there are certainly copyist errors in our manuscripts, God has preserved its essential message. Too often we as Christian leaders affirm the inspiration and authority of Scripture but fail to mention that we don’t have perfect copies. This “lie of omission” then comes back to bite us when our young people go off to study in the real world and learn about the imperfection of our biblical manuscripts. Better to equip them by teaching the truth of textual variation in a safe place, where they can ask questions and hear honest and affirming answers.

- Emphasize that Mark’s Gospel strongly affirms the historical reality of the resurrection and the resurrection appearances. The fact that Mark does not narrate resurrection appearances does not change his strong affirmation of the historicity of the resurrection.

- As noted above, I would explain the options, but conclude with Mark’s call for faith and action in 16:8. This is the proper response to the resurrection announcement: faith, not fear.

The account of the woman caught in adultery

The textual evidence of John 7:53–8:11

As with the longer ending of Mark’s Gospel, the account of the woman caught in adultery was almost certainly not an original part of John’s Gospel. Both the external and the internal evidence weigh strongly against it.

In terms of external evidence, the passage is absent from our earliest Greek manuscripts. This includes the earliest papyri (𝔓66 and 𝔓75) and four of our earliest majuscule manuscripts, Codex Sinaiticus (ℵ), Codex Vaticanus (B), Codex Alexandrinus (A; 5th cent.), and Codex Ephraemi (C; 5th cent.).5 The passage begins to appear in Greek manuscripts around the fifth century. The patristic evidence supports this conclusion. C. K. Barrett notes the passage is omitted by all the early church fathers, “including Origen, Cyprian, Chrysostom, and Nonnus, who, in expounding, commenting, or paraphrasing, pass directly from 7.52 to 8.12.”6

The internal evidence is also against the passage’s placement in John. The Greek vocabulary and style differ from John’s elsewhere, and the passage interrupts the flow of John’s Gospel. When it is omitted, the transition from 7:52 to 8:12 is smooth, as Jesus continues teaching in the temple and debating the religious leaders there.

Explore text critical issues using the Textual Variants section in Logos’s Exegetical Guide.

While the vast majority of New Testament scholars do not believe that this passage was originally part of John’s Gospel, many consider it to be an authentic story about Jesus that was passed down independently of the canonical Gospels. Jesus’s emphasis on God’s love and mercy for sinners and his strong rebuke of the religious leaders’ hypocrisy fit well with what we know of the historical Jesus. Support for this idea of a “floating tradition” is that while the passage appears after John 7:52 in most manuscripts, in a few it appears elsewhere in John (after 7:36; after 7:44, after 21:25) and even in a different Gospel (after Luke 21:38)!7

So while Mark 16:9–20 is likely a scribal addition meant to fill in an apparent gap in Mark’s narrative, John 7:53–8:11 is probably an authentic Jesus tradition that eventually found its way into John’s Gospel.

How to handle John 7:53–8:11 when preaching

As in the case of Mark’s ending, the account of the woman caught in adultery provides a good opportunity to give your congregation a more mature understanding of the biblical text. We don’t need to “dumb down” reality or protect them from the truth. Instead, use this as an opportunity to acknowledge variations within the biblical text, to affirm its reliability, and to explain how the tools of textual criticism can be used to establish something very close to the original.

We don’t need to “dumb down” reality or protect them from the truth.

Several years ago, I was teaching through John’s Gospel in a local church setting. When I reached this point (7:53–8:11), I announced that we were going to take a week off of John’s Gospel and discuss this passage, which was probably not originally located here in John but was almost certainly an authentic story about Jesus. In this way, they got to hear this episode taught as a wonderful example of Jesus’s teaching about God’s grace and mercy. The next week, we returned to John’s Gospel and for the next few months carried on, following John’s narrative theology to the end of his Gospel.

Conclusion

In this article, we have discussed the only two textual variants of significant length in the New Testament, the longer ending of Mark (16:9-20) and the account of the woman caught in adultery (John 7:53–8:11). In both cases, we concluded that these passages were not originally part of their respective Gospels, and we offered suggestions on how they could be preached. Mark’s Gospel likely originally ended at 16:8 with the announcement of the resurrection. This ending can be powerfully preached as a call to proclaim Christ’s resurrection with an attitude of faith, not fear. While the account of the adulterous woman was almost certainly not an original part of John’s Gospel, it is worthwhile to preach it as an authentic story about Jesus that demonstrates God’s grace and forgiveness.

As Christians, we love to speak in absolute terms. We have an infinite God who is all-knowing, all-powerful, and eternal. His actions are perfect and his Word is infallible. Yet we must also acknowledge that, as humans, we are finite beings. Our knowledge of God will always be limited, and our interpretation of his Word will always be imperfect (1 Cor 13:9–12).

Whatever we might propose about the autographs of Scripture, the copies that we have contain flaws. But we also believe that the Spirit of God has preserved its essential message and will continue to guide his servants in its faithful interpretation and application. When it comes to teaching God’s Word to God’s people, then, the best policy is to speak the truth with clarity, to acknowledge our own limitations with humility, and to trust the Lord, who affirms that “my word that goes out from my mouth … will not return to me empty, but will accomplish what I desire” (Isa 55:11 NIV).

Related resources for further study

A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, Second Edition

Save $1.50 (5%)

Price: $28.49

-->Regular price: $29.99

Revisiting the Corruption of the New Testament

Save $1.20 (5%)

Price: $22.79

-->Regular price: $23.99

Textual Criticism of the Bible: Revised Edition (Lexham Methods Series)

Save $8.75 (35%)

Price: $16.24

-->Regular price: $24.99

Myths and Mistakes in New Testament Textual Criticism

Save $1.40 (5%)

Price: $26.59

-->Regular price: $27.99

New Testament Textual Criticism: A Concise Guide

Save $5.25 (35%)

Price: $9.74

-->Regular price: $14.99

The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable?

Save $0.60 (5%)

Price: $11.39

-->Regular price: $11.99

New Testament Text and Translation Commentary

Save $9.10 (35%)

Price: $16.89

-->Regular price: $25.99

A Student’s Guide to Textual Criticism of the Bible

Save $0.55 (5%)

Price: $10.44

-->Regular price: $10.99

Perspectives on the Ending of Mark: Four Views

Save $0.50 (5%)

Price: $9.49

-->Regular price: $9.99

Does Mark 16: 9–20 Belong in the New Testament?

Save $0.63 (5%)

Price: $12.02

-->Regular price: $12.65

Related articles

- How Textual Critics Reconstruct the Bible’s Text: 6 Key Principles

- What Is Textual Criticism of the Bible? A Crash Course

- Original Language Research: What to Do, What Not to Do

- How the Dead Sea Scrolls Changed Our Bibles: 3 Exciting Examples

- Top Preaching Tools & Resources That Belong in a Pastor’s Library

2 weeks ago

33

2 weeks ago

33

English (US) ·

English (US) ·