To profess the Christian faith is to make a profound theological and political claim. If God raised Jesus from the dead, that necessitates we confess him as Lord. But to declare Jesus is Lord in a world of many lords is a dangerous thing to do.

Over the course of Christian history, Christians have explained the connection between the ideal earthly political order and the kingdom of God in different ways, giving us what many call political theology. One of the contributions to this project that emerges from a uniquely American context is Black theology: the theological emphases and traditions originating in enslaved communities and developing throughout American history in response to white supremacy’s political domination and economic exploitation.

In the face of racist oppression, Black Christians have looked to the Scripture to frame, not only methods of political survival, but also methods of political resistance.

A contextualized theology: race, religion & resistance

To invoke Black theology is to invoke political theology. As James Cone began his classic, A Black Theology of Liberation, “Christian theology is a theology of liberation.” By this, Cone summarized a framing of Christian theology that is especially native to Christianity in Black American communities: an understanding that Christ’s primary purpose was and is to set us free, both spiritually and materially.

What this means, then, is that, particularly for Black Christian communities, the Christian faith has always been political. It has always been concerned with matters of power, resources, justice, and communities.

The Christian faith has always been political.

In order to properly understand these commitments of Black political theology, however, we have to understand the context of that theology: Black political thought.

Blackness as political reality

To invoke Blackness is to invoke a political reality. Europeans created the category of race, particularly the concepts of “Blackness” and “whiteness,” to justify the continued enslavement of Africans. Race is not an ontological reality, but it is a political one formed for the purpose of political domination and economic exploitation. As W. E. B. Du Bois said in his autobiography, “the black man is a person who must ride ‘Jim Crow’ in Georgia,” indicating that Blackness is first and foremost a political category, a category imposed to enforce a social position.

As such, Blackness requires a sociopolitical response: How will people gather themselves in order to survive and thrive in such a world?

Black theology as liberation theology

What is true of Black political thought, then, is also true of Black theology. As political theorist Michael Dawson argues, “the core concepts … have developed out of the experiences of slavery and the forced separation of the races during the period of retrenchment that followed the post-Civil War Reconstruction period.” For Black Christians, this history birthed particular political and theological foci.

Most immediately, Black Christians suffering under the regime of racialized chattel slavery clearly saw themselves in the Scriptures: the people of Israel declared to be a people following their liberation from Egypt. While slavers insisted on hiding the liberative elements of the Scriptures from the enslaved, in some cases by even aggressively abridging the text, Black men and women saw the God of the Scriptures and were comforted by the fact that God was a God of liberation. The same God who set the Hebrew slaves free from Egyptian oppression and who set humanity free in Christ would set them free from white enslavers. In fact, to believe any less would be to deny the Scriptures themselves.

Explore Black Theology using Logos’s Factbook.

3 portraits of Black political theology

Perhaps the best way to see this is to focus on three exemplary individuals:

- The influential free Black abolitionist David Walker

- The fearless antilynching activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett

- The Baptist preacher and civil rights advocate Martin Luther King Jr.

These three, operating in three different eras of American history, battled particular racist evils. They did so, not only as significant political thinkers, but also as Christians, marshaling the resources of Scripture to justify and strengthen their claims.

The abolitionist: David Walker

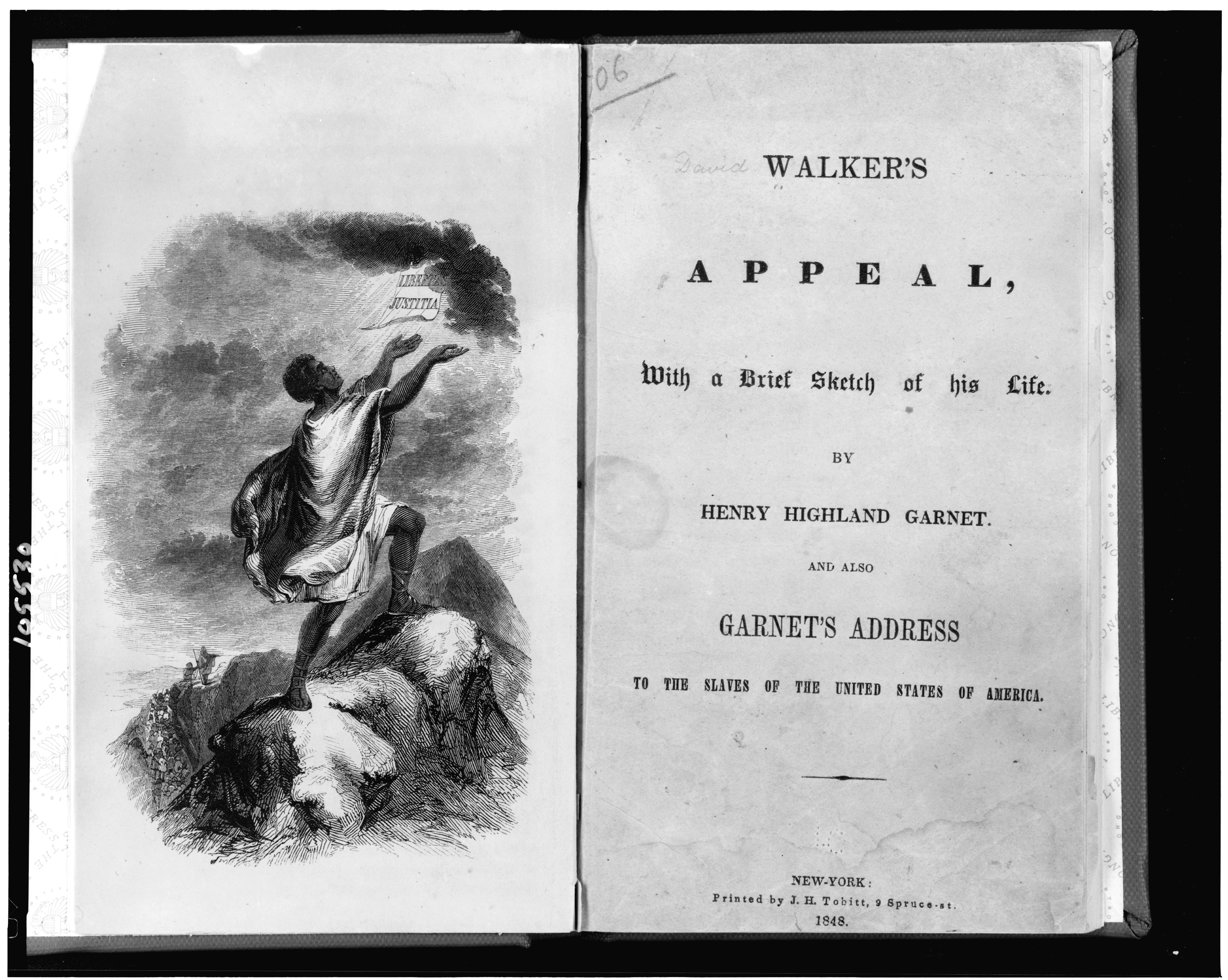

Because he only wrote one text, we typically fail to consider David Walker a significant political theorist, much less political theologian. However, his An Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World is one of the most significant political documents of the nineteenth century. As a strident advocate for the freedom of Black people and as a Christian, he wrote his Appeal in order to make powerful political and theological arguments for abolition.

The book’s final, third edition came in 1830. When Walker wrote it, much of the abolitionist movement at that time was gradualist, arguing that advocating for the immediate eradication of racialized chattel slavery would be too much of a burden. After Walker’s Appeal, however, that sentiment shifted. Walker’s visceral, persuasive, and deeply Christian appeal to the consciences of white people and the intelligence and sensibilities of both enslaved and free Black people made clear that slavery was an evil that needed to be done away with by any means necessary.

The title page to An Appeal to Heaven along with an illustration. The illustration depicts a slave on top of a mountain raising his arms to paper containing the words LIBERTAS (liberty) and JUSTITIA (justice).

The title page to An Appeal to Heaven along with an illustration. The illustration depicts a slave on top of a mountain raising his arms to paper containing the words LIBERTAS (liberty) and JUSTITIA (justice).And while political, we also must not forget that it is also an inextricably Christian document. Walker not only enters the conversation with a solid understanding of what freedom is, but also with an understanding of what it means to be a Christian.

The Scriptures saturate Walker’s text, but not through proof texts. Instead, Walker weaves the language of the Bible into the text such that if the reader did not know the Bible they wouldn’t notice the references. This is keeping with the ways that the enslaved would often learn the Scriptures. Often forbidden to read and write, the enslaved would learn Scripture by memory. Knowing this, Walker soaked his Appeal in Scripture, whether it was Jesus’s words in the Gospels or the apocalyptic language of Revelation.

The latter set the tone of his critique. The evil perpetuated by white enslavers, especially those who claimed to be Christian, was one that was worthy of divine judgment—and that divine judgment was sure to come. In one passage, Walker echoed Paul’s narration of judgment in Romans 1, saying, “The Americans, having introduced slavery among them, their hearts have become almost seared, as with a hot iron, and God has nearly given them up to believe a lie in preference to the truth.” Walker’s slight tweak of Romans 1:24–25, by inserting the word “nearly” communicated a fierce theological and political point: White Christians had a chance to repent, but the window was closing before they would otherwise face the Lord’s wrath for the evils of chattel slavery.

The Appeal is worthy of being read in its entirety. In it the reader will find a text that is the result of a Black man raised in the Christian Scriptures, applying them with clear eyes as he looks out on the American landscape. For Walker, as for many Black American Christians, this manifested itself in articulating an anti-oppression faith.

The activist: Ida B. Wells-Barnett

Ida B. Wells is the single most important person in the history of the anti-lynching movement. From the late nineteenth century to the early twentieth century, mobs brutally killed thousands of Black men, women, and teenagers in circumstances often rife with racial, sexual, and gendered falsehoods. Over decades, Wells, through her editorial and speaking career, undermined the false narratives that stoked the flames of these lynchings. Through her investigations, she publicized the most public and brutal instantiation of white supremacy in American history.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett.Integral to her work was her understanding of what constituted true Christianity. As she investigated the communities in which lynchings took place, one of the constant questions she would publicly ask was how so-called Christians could do such things. In 1899, when Wells reflected on the brutal lynching of Sam Hose, in which a mob cut off his ears and fingers, castrated him, and burned him alive, she wrote: “No other nation on earth, civilized or savage, has put to death any human being with such atrocious cruelty as that inflicted upon Samuel Hose by the Christian white people of Georgia.” This and similar declarations were meant to shock a nation that claimed to be Christian into actually being obedient to Christ. However that Christianity was conceived, it could not include burning Black men and women alive.

Similar to David Walker, Wells’s editorials did not use the Scriptures as a series of proof texts. Yet they provided the foundation for the ethic she assumed. She saw, particularly, Christ’s commands in the Gospels as morals that actually bound the Christian, and thus was dismayed when white lynching communities revealed by their actions that they had little regard for Christ. In a way, her sentiment is emblematic of Black political theology at large.

Wells internalized the Scriptures and mobilized them against the oppression of the marginalized. In her era in which the oppressed were the lynched, she expended her life to dismantle that violent regime.

The advocate: Martin Luther King Jr.

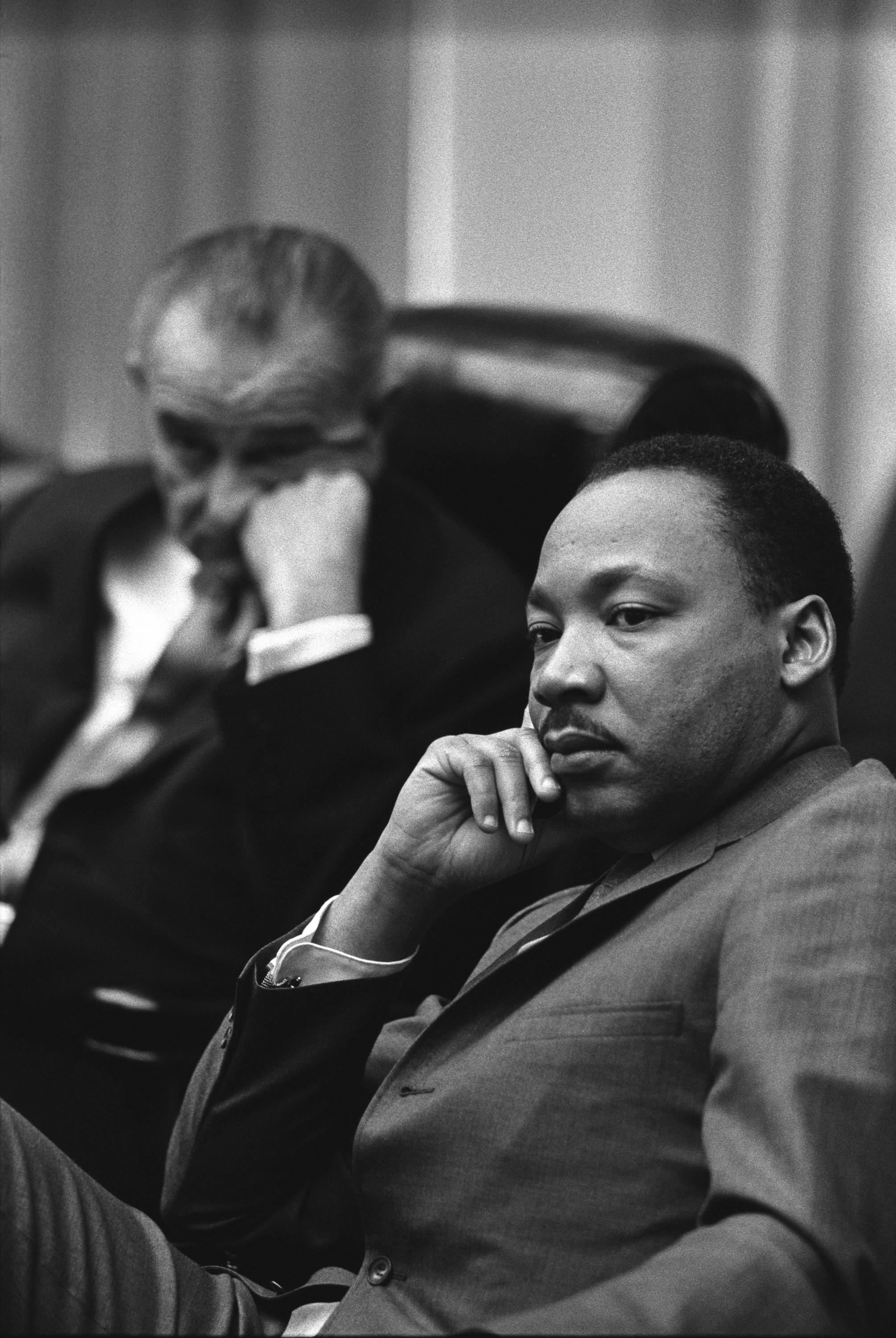

Perhaps the most recognizable example of Black political theology, however, is Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

As a Baptist preacher and civil rights activist, Martin King made significant contributions both to American political thought and Black political theology. One of the most significant portions of his legacy, besides popularizing an effective method of nonviolent civil resistance, was his diagnosis of the United States’s ills. As he told the staff of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1967,

We must see now that the evils of racism, economic exploitation and militarism are all tied together. You can’t really get rid of one without getting rid of the others. The whole structure of American life must be changed. America is a hypocritical nation and we must put our own house in order.

Those triple evils were the same evils that Wells and Walker fought. It was greed that precipitated racialized chattel slavery. It was greed, racism, and violence that combined to form the lynching regime. And now these same three evils fed Jim Crow. In fact, the naming of those three evils may be one of the most significant contributions of Black political theology: an explicit naming of the powers and principalities that feed oppression and a commitment to advocacy on behalf of and in solidarity with the oppressed.

Martin Luther King Jr. with President Lyndon Johnson.

Martin Luther King Jr. with President Lyndon Johnson.King’s devotion to the Scriptures was most clear in his political tactics, specifically his commitment to nonviolence. He explicitly grounded this commitment in Christ’s words. King was deeply convinced that nonviolence was the Lord’s intention for his people, so it was the message that he preached.

But the distinctiveness of his approach cannot be overstated. King argued that the ideal political approach is to insist that no human being is an enemy, but rather a human being to be loved. He argued that even those who commit evil are not the enemy: injustice is. He taught that suffering could actually be redemptive. None of these claims make sense apart from the Christian Scriptures, particularly the words of Jesus.

But like Wells and Walker, King internalized the Scriptures and mobilized them against the most prominent form of oppression that he saw around him. For King’s era, that evil was Jim Crow, the regime of racist segregation and exploitation that reigned in American history for the century following the Civil War.

Black political theology in brief

Although we could mention many others (e.g., Henry Highland Garnet, Jarena Lee, J. Deotis Roberts, James Cone, Fannie Lou Hamer), the three figures above serve as just a few of the names in the pantheon of Black political theologians.

Characteristic to Black political theology are two impulses, both led by Scripture:

- An affirmation of the humanity and dignity of Black people

- A relentless resistance to all forms of political and economic oppression

Black political theology is one that keeps the Exodus before its eyes, as the people of Israel were commanded (Deut 6:20–24). Just as the Israelites were to remind themselves and their children of the Lord’s deliverance from Egypt, the land of slavery, the Black political theologian—especially in an American context—can never forget the United States’s dark history.

Yet that history does not dictate the Black political theologian’s hope. That hope is found in a just and loving God. It is a hope found in a Christ whose mission was and is “to proclaim good news to the poor … to proclaim freedom for the prisoners and recovery of sight for the blind, [and] to set the oppressed free” (Luke 4:18 NIV).

Recommended resources on Black theology and political thought

- Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?

- Malcolm X Speaks: Selected Speeches and Statements

- Ida B. Wells, The Light of Truth: Writings of an Anti-Lynching Crusader

- David Walker, An Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World

- J. Deotis Roberts, A Black Political Theology (currently in production as part of this Logos collection)

- James Cone, Black Theology and Black Power

4 weeks ago

28

4 weeks ago

28

English (US) ·

English (US) ·